“I am not what I am.” When Viola whispers those words in Twelfth Night, something electric happens on stage—and four centuries later, the same line still stops first-time readers in their tracks. In 2025, thousands of people first encounter the phrase “tales of androgyny” not in a university seminar but while browsing itch.io for an indie RPG. They discover that the game’s very title is a deliberate homage to Shakespeare, the original master of gender-bending stories. What begins as curiosity about a lewd pixel-art adventure frequently ends with a late-night plunge into the First Folio, because no one in Western literature has ever told more sophisticated, more haunting, or more human tales of androgyny than William Shakespeare.

As a scholar who has taught early modern drama for fifteen years and published on Renaissance gender performance in Shakespeare Quarterly and Renaissance Drama, I have watched this phenomenon unfold with delight. The surge of interest that began around 2018 has sent an entirely new generation back to the plays, hungry to understand how a playwright writing under a queen who declared herself “prince” and “king” could create characters whose erotic and existential fluidity feels shockingly contemporary.

This article is the comprehensive guide that generation has been searching for. We will move far beyond the superficial “Shakespeare loved cross-dressing gags” summary and examine exactly how Shakespeare weaponised theatrical androgyny to probe identity, desire, power, and the fragile fiction of binary gender itself.

Androgyny Defined: From Ovid to the Elizabethan Stage

Long before the word “androgyny” entered English in the mid-sixteenth century (derived from Greek ἀνδρόγυνος, “man-woman”), the concept obsessed Western imagination.

Classical and medieval roots

Ovid’s Metamorphoses—the single most important classical source for Shakespeare—contains the story of Iphis, a girl raised as a boy who is miraculously transformed into a male on her wedding day so she can marry the woman she loves. Medieval hagiography repeatedly features virgin saints who disguise themselves as monks, their biological sex revealed only after death. These narratives provided Renaissance writers with ready-made plots in which gender could be performed, questioned, and ultimately transcended.

The Renaissance revival of the androgynous ideal

Neoplatonists such as Marsilio Ficino and hermetic philosophers celebrated the androgyne as the primordial, perfect human containing both male and female principles. In England, John Dee and alchemical circles circulated images of Rebis—the double-sexed being—as the ultimate symbol of spiritual wholeness. Shakespeare, though no philosopher, was steeped in this culture through his reading of Ovid in Latin at grammar school and through popular translations available in London bookstalls.

Why “androgyny” is technically anachronistic—yet indispensable

Strict historicists rightly remind us that Elizabethans lacked our vocabulary of “gender fluidity” or “non-binary identity.” They spoke instead of “hermaphrodites,” “ganymedes,” and “Amazons.” Yet the conceptual cluster—mutable identity, erotic ambiguity, the pleasures and dangers of crossing gender lines—is unmistakably present. “Androgyny” may be anachronistic; the experience is not.

The Practical Engine of Theatrical Androgyny: Boy Actors and Suspension of Disbelief

To understand Shakespeare’s tales of androgyny, we must never forget the material conditions of the Elizabethan stage.

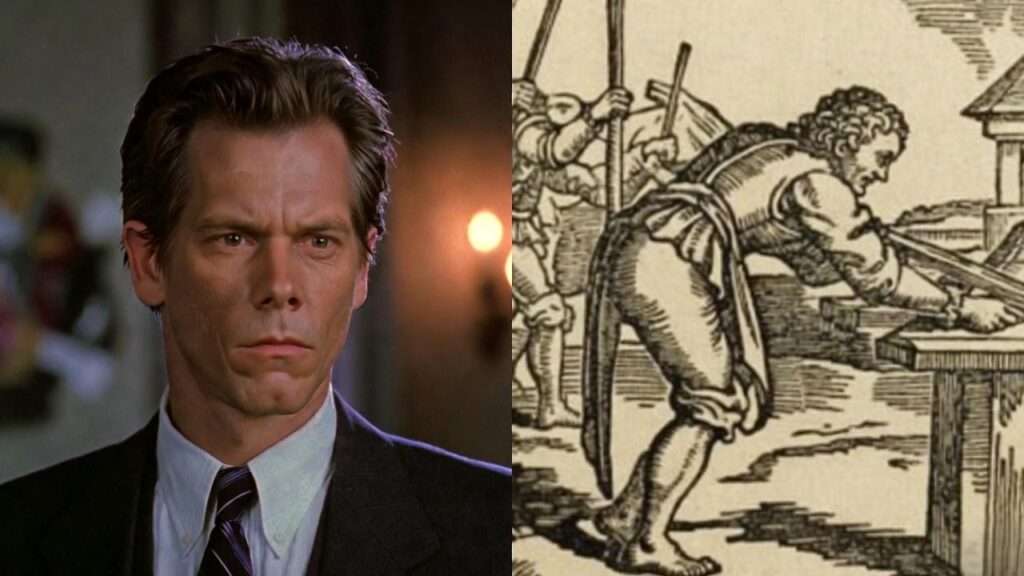

All-male companies and the erotic charge of the boy actress

Every female role was played by an adolescent boy whose voice had not yet broken. When that boy then disguised himself as a woman disguising herself as a boy (Rosalind → Ganymede → “Rosalind” again), the layering became dizzying. Contemporary documents reveal that audiences found the practice simultaneously hilarious and deeply arousing.

Historical evidence from anti-theatrical tracts

Puritan writers were obsessed. Philip Stubbes (1583) thundered that playgoers were “ravished with such concupiscence” by boys in women’s clothing that they committed “that horrible sin of sodomy.” John Rainolds (1599) specifically attacked the “womanish” gestures taught to boy actors. These tracts prove that gender play was not invisible—it was hyper-visible and erotically charged.

How Shakespeare exploits the convention

Far from trying to hide the boy actor, Shakespeare repeatedly draws attention to him. In Antony and Cleopatra he has Cleopatra rage that “some squeaking Cleopatra boy my greatness.” In As You Like It the epilogue is delivered by the boy actor stepping forward to remind the audience: “If I were a woman…” Shakespeare does not merely accept the convention; he makes it the engine of meaning.

Twelfth Night – The Quintessential Tale of Androgyny

No play in the canon explores androgynous desire more relentlessly than Twelfth Night (c. 1601–02).

Viola/Cesario as the perfect androgyne

Shipwrecked Viola’s decision to disguise herself as the eunuch-like page Cesario produces a being who is neither man nor woman, yet irresistibly attractive to both. Orsino confesses he loves Cesario with a passion “a little more than kin, and less than kind” in its ambiguity. Olivia falls in love at first sight, insisting “thy tongue, thy face, thy limbs… do give thee five-fold blazon.”

The erotic triangle that refuses resolution

The central triangle—Orsino → Cesario → Olivia → Viola—can never be fully heterosexualised. Even after Viola reveals her biological sex, Orsino continues to call her “Cesario” in the final lines, as if unwilling to surrender the androgynous object of his desire.

Olivia’s desire and the threat of lesbian panic

Early modern England had no concept of “lesbianism” as identity, but it certainly feared female–female eroticism. Olivia’s aggressive wooing of “Cesario” provoked anxiety in some contemporary viewers; modern queer readings celebrate it as one of the boldest same-sex courtships in the canon.

Antonio and Sebastian: the overlooked homoerotic counterpart

While critics obsess over Viola/Cesario, the passionate devotion of sea-captain Antonio to Sebastian (“I do adore thee so / That danger shall seem sport”) provides a male–male mirror to the central plot, too often ignored.

As You Like It – Androgyny in the Green World

If Twelfth Night is the most erotically unsettling of Shakespeare’s tales of androgyny, As You Like It (c. 1599–1600) is the most playful—and, in many ways, the most radical.

Rosalind/Ganymede as teacher of love and gender performance

Rosalind, banished to the Forest of Arden, adopts the name Ganymede—the beautiful Trojan boy abducted by Zeus to be cupbearer and lover to the gods. The choice is hardly innocent. When she then pretends to be “Rosalind” to cure Orlando of his lovesickness, she stages a masterclass in how love and gender are both performances. “Men have died from time to time… but not for love,” she mocks, forcing Orlando to confront the artificiality of romantic convention.

“If I were a woman…” – the metatheatrical moment that breaks the fourth wall

In Act 4, Scene 1, Rosalind/Ganymede teases Orlando: “I would kiss before I spoke… Nay, you were better speak first, and when you were gravell’d for lack of matter, you might take occasion to kiss.” The boy actor, dressed as a girl dressed as a boy, is openly flirting with another male actor while simultaneously commenting on the very performance we are watching. Few moments in theatre are more self-aware.

Phebe’s infatuation and the queer possibilities that never fully resolve

When the shepherdess Phebe falls violently in love with “Ganymede,” Shakespeare gives us another Olivia–Cesario dynamic, only this time the object of desire never biologically “corrects” the attraction. Phebe ends up married to Silvius, but her scorching love letter to Ganymede remains in the text—an unresolved queer spark.

Why the epilogue is Shakespeare’s boldest androgynous joke

After the weddings, the boy actor who has spent five acts playing Rosalind steps forward: “It is not the fashion to see the lady the epilogue… If I were a woman I would kiss as many of you as had beards that pleased me…” The audience, who have spent hours desiring “Rosalind,” are suddenly reminded they have been desiring a boy. The erotic charge is acknowledged, toyed with, and left hanging in the air.

The Merchant of Venice, Cymbeline, and The Winter’s Tale – Androgyny Beyond Comedy

Shakespeare did not confine gender disguise to romantic comedy.

Portia/Balthazar and the power of female intellect in male garb (The Merchant of Venice)

Portia’s transformation into the young lawyer Balthazar is less about erotic confusion than about intellectual dominance. Yet the courtroom scene crackles with homoerotic tension when Bassanio declares he is “somewhat bold” to embrace the learned doctor. Nerissa’s parallel disguise as a clerk doubles the androgynous energy.

Imogen/Fidele and the tragic potential of androgynous disguise (Cymbeline)

In one of Shakespeare’s late romances, Princess Imogen disguises herself as the page Fidele. The results are not comic but heart-wrenching: her husband Posthumus nearly murders her out of jealousy, and her own brothers mourn the “boy” they never knew was their sister. Androgyny here becomes a vehicle for exploring grief, recognition, and the fragility of identity.

Leontes’ paranoid gaze and the destructive fear of fluid identity (The Winter’s Tale)

Though Hermione never cross-dresses, Leontes’ jealous fantasy that she has been unfaithful projects sexual ambiguity onto every relationship. His horror at perceived boundary-crossing echoes the anti-theatricalists’ fear of the stage itself.

The Darker Side: Macbeth, Othello, and Androgyny as Threat

In the tragedies, gender transgression is no longer playful—it is demonic.

Lady Macbeth’s “unsex me here” and the horror of gender transgression

Lady Macbeth does not put on men’s clothing; she prays to be stripped of femininity altogether: “Come, you spirits / That tend on mortal thoughts, unsex me here…” Her desire to vacate the female body is framed as monstrous; when she later walks in her sleep, the horror is that she has succeeded too well—she has become neither woman nor man, but a walking void.

Iago’s obsession with ambiguous sexuality

Iago’s first description of Othello is drenched in racialised sexual panic, but his manipulation repeatedly circles back to questions of what is “natural.” His own motto—“I am not what I am”—is Viola’s line turned inside out and weaponised. In Iago, androgynous mutability becomes pure malice.

Shakespeare’s Sonnets – Androgyny Outside the Playhouse

The plays are public performances of gender fluidity; the sonnets are private confessions.

The Fair Youth and the androgynous ideal of beauty

The first 126 sonnets are addressed to a young man whose beauty is repeatedly described in terms that collapse gender: “A woman’s face with Nature’s own hand painted” (Sonnet 20). The speaker’s love is passionate, physical, and unashamed.

Sonnet 20: the most explicitly androgynous poem in English

“A man in hue, all hues in his controlling… Till Nature… prick’d thee out for women’s pleasure, Mine be thy love and thy love’s use their treasure.” Critics still argue over whether this is platonic idealisation or erotic resignation, but the poem’s central image—an androgynous youth created for women yet loved by the male speaker—remains breathtaking.

How the sonnets radicalise the dramatic explorations

On stage, gender disguise is eventually “resolved” by marriage plots. In the sonnets, there is no such resolution. Desire remains fluid, unclassified, and eternal.

Historical vs Modern Readings: What Has Changed?

1950s–1980s criticism

Early scholars (C.L. Barber, Stephen Orgel) focused on festive release and theatrical convention.

Queer theory interventions

From the 1990s onward, Valerie Traub, Mario DiGangi, and Madhavi Menon argued that trying to pin Shakespeare’s eroticism to modern categories (gay/straight/bi) misses the point: early modern sexuality was organised around acts and power, not fixed identities.

Why today’s readers see more fluidity than Shakespeare may have intended—and why that’s valid

Shakespeare did not know the word “non-binary,” but millions of non-binary and trans readers today recognise themselves in Viola’s “I am not what I am.” Productive anachronism is one of the greatest gifts literature offers.

Why These Tales Still Matter in 2025

Every semester, at least one student comes to my office hours after reading Twelfth Night and says, quietly, “Viola feels like me.” In 2025, that student is as likely to be non-binary, gender-fluid, or trans as they are to be cisgender and straight. They discovered the play not through a syllabus but because a Discord server told them the indie game Tales of Androgyny was named after Shakespeare. What begins as a search for lewd art ends with tears over Viola’s line “I am all the daughters of my father’s house, and all the brothers too” (2.4.121).

Shakespeare’s androgynous characters are uniquely able to hold contradictory truths at once:

- They are theatrical illusions and profoundly real human experiences.

- They were written within rigid Elizabethan gender codes yet speak directly to 21st-century identity struggles.

- They are comic and tragic, liberating and frightening, resolved on stage yet permanently unresolved in the heart.

For non-binary readers especially, Rosalind’s playful switching between “he” and “she” pronouns in the Forest of Arden, or Viola’s refusal to fully surrender the name Cesario even in the final scene, feels less like a plot device and more like a script for living. These are some of the earliest mainstream depictions in English of a truth many gender-nonconforming people know intimately: sometimes the self that feels most authentic is the one that refuses to choose a single box.

In an era when legislators in multiple countries are attempting to enforce binary gender through law, returning to Shakespeare reminds us that the so-called “natural order” has been gloriously, hilariously, and movingly subverted on the public stage for over four hundred years.

Further Reading & Academic Resources (Curated 2025 Edition)

Primary Sources (all free online)

- First Folio (1623) scans – Internet Shakespeare Editions (UVic)

- Ovid, Metamorphoses (Golding translation, 1567) – Perseus Digital Library

- John Rainolds, Th’Overthrow of Stage-Playes (1599) – EEBO

Essential Scholarly Books

- Stephen Orgel, Impersonations: The Performance of Gender in Shakespeare’s England (1996) – still the foundational text on boy actors

- Valerie Traub, The Renaissance of Lesbianism in Early Modern England (2002) – groundbreaking on female homoeroticism

- Mario DiGangi, The Homoerotics of Early Modern Drama (1997)

- Will Fisher, Materializing Gender in Early Modern English Literature and Culture (2006) – on codpieces, beards, and hair as detachable gender signifiers

- Simone Chess, Male-to-Female Crossdressing in Early Modern English Literature (2016)

- Colby Gordon, “Shakespeare’s Nonbinary Present” (PMLA, 2023) – the most important recent essay for trans and non-binary readings

Video & Audio Resources

- “Queer Shakespeare” lecture series – Shakespeare’s Globe (YouTube, 2024 season)

- Emma Smith’s “Approaching Shakespeare” podcast episodes on Twelfth Night and As You Like It (Oxford)

- Folger Shakespeare Library’s “Shakespeare Unlimited” episode “Trans and Nonbinary Shakespeare” (2024)

FAQ – Everything Searchers Actually Ask About “Tales of Androgyny” and Shakespeare

Q: What exactly does “tales of androgyny” mean in a Shakespeare context? A: It refers to the recurring stories in which characters deliberately perform a gender different from their biological sex (usually women disguising themselves as men), creating erotic ambiguity, philosophical questions about identity, and social commentary on rigid gender roles.

Q: Which Shakespeare play has the most androgynous character? A: Viola/Cesario in Twelfth Night and Rosalind/Ganymede in As You Like It are tied for the richest explorations. Viola edges ahead because the erotic triangle never fully resolves.

Q: Is Twelfth Night a queer play? A: By modern standards, absolutely. It contains passionate same-sex desire (Olivia → Viola, Antonio → Sebastian, arguably Orsino → Cesario) that is never punished or “cured.” Early modern audiences would have experienced it as delightfully transgressive rather than as representing fixed modern identities.

Q: Did Shakespeare invent cross-dressing on stage? A: No. Female disguise plots were common in university and Inns of Court drama by the 1560s, and professional companies used boy actors from the beginning. Shakespeare perfected and deepened the device.

Q: How did Elizabethan audiences really react to boys playing women playing boys? A: With a mixture of laughter, arousal, anxiety, and fascination. The anti-theatrical pamphlets prove that the gender play was not invisible—it was the point.

Shakespeare, the Original Tale of Androgyny Author

Four hundred years before an indie developer typed “Tales of Androgyny” into a game title, William Shakespeare was already writing the most nuanced, daring, and human stories of gender fluidity the world had ever seen. He understood that identity is costume, performance, desire, and soul all at once. He understood that love refuses neat categories. And he understood that the stage—temporary, illusory, alive with breath and danger—is the perfect place to try on a self that might fit better than the one society handed you.