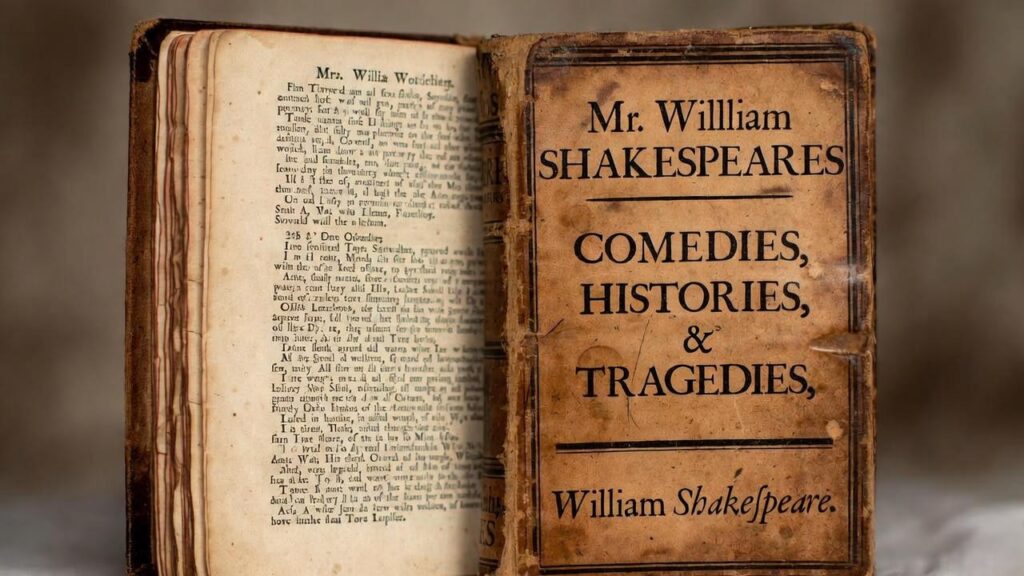

What if the version of Julius Caesar you know—full of iconic lines like “Friends, Romans, countrymen” and “Et tu, Brute?”—had been subtly altered over centuries by editors adding punctuation, changing words, or dividing scenes? The original printing of Caesar offers a purer, more immediate glimpse into Shakespeare’s theatrical world, first appearing not in a standalone edition but in the landmark 1623 First Folio. This collection, compiled by Shakespeare’s fellow actors, preserved the play in a remarkably clean and authoritative text derived from performance sources. For scholars, performers, and enthusiasts seeking the most authentic Shakespearean experience, understanding this original printing unlocks deeper insights into the Bard’s craft, rhetoric, and stage intentions.

In an era when many plays circulated in flawed “quarto” editions—often pirated or reconstructed from memory—Julius Caesar evaded such corruption. Its debut in print came seven years after Shakespeare’s death, within the pages of Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies, commonly known as the First Folio. This article delves into the historical context, textual purity, and lasting significance of this original printing, providing the comprehensive guide you’ve been searching for to connect directly with Shakespeare’s voice.

The Historical Context of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar

Composition and Early Performances (c. 1599)

Scholars date Julius Caesar to around 1599, making it one of Shakespeare’s earliest tragedies and possibly the inaugural play at the newly built Globe Theatre. A pivotal piece of evidence comes from the diary of Swiss traveler Thomas Platter the Younger, who visited London in September 1599. On the 21st, he recorded attending a performance of “the tragedy of the first Emperor Julius Caesar” at a “straw-thatched house” (widely accepted as the Globe), noting about 15 characters and graceful dancing at the end—a common Elizabethan theatrical flourish.

This timing aligns perfectly: the play is absent from Francis Meres’ 1598 catalogue of Shakespeare’s works (Palladis Tamia), yet stylistic parallels with Hamlet (c. 1600) and Henry V (1599) support a 1599 composition. The Globe, constructed from timbers of the dismantled Theatre playhouse, opened that year on Bankside, and Julius Caesar‘s grand rhetoric and crowd scenes would have suited the new open-air venue spectacularly.

Politically, the play resonated in late-Elizabethan England. With Queen Elizabeth I aging and childless, anxieties over succession abounded. Themes of ambition, assassination, and republicanism mirrored contemporary fears of civil unrest, subtly commenting on power dynamics without direct allegory.

Shakespeare’s Sources and Dramatic Innovations

Shakespeare drew primarily from Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans, translated by Sir Thomas North in 1579 (reprinted 1595). North’s vivid prose supplied parallel biographies of Caesar, Brutus, and Antony, which Shakespeare condensed masterfully.

Key innovations include:

- Compressing the timeline: Historical events spanning years unfold in days for dramatic intensity.

- Inventing memorable lines: “Et tu, Brute?”—though rooted in tradition—gains its fame here.

- Elevating rhetoric: The funeral orations (Brutus’ logical prose vs. Antony’s emotive verse) showcase Shakespeare’s mastery of persuasion.

These choices transformed historical biography into timeless tragedy, exploring loyalty, honor, and the perils of power.

Publication History: Why No Quarto Edition for Julius Caesar?

Quartos vs. Folios in Shakespeare’s Era

In Elizabethan and Jacobean England, plays appeared in two main formats:

- Quartos: Small, inexpensive books printed from sheets folded twice (eight pages per sheet). Often rushed for quick sales, many were “bad quartos”—unauthorized, pirated via audience memory or actor leaks, riddled with errors (e.g., contested texts of Hamlet or Romeo and Juliet).

- Folios: Larger, prestigious volumes (sheets folded once, four pages per sheet), reserved for serious literature.

Of Shakespeare’s 36 canonical plays, 18 appeared in quartos during or shortly after his lifetime. But Julius Caesar was not among them—no quarto until 1684, well into the Restoration era.

Theories on the Absence of a Quarto

Why did this popular play escape pre-Folio printing? Experts propose:

- Company Protection: The Lord Chamberlain’s Men (later King’s Men) tightly guarded successful scripts to prevent rival companies from performing them. Julius Caesar, a staple with frequent revivals, was too valuable to risk piracy.

- Theatrical Demand: High performance frequency reduced need for printed sales; the play earned more on stage.

- Comparison: Like Macbeth, The Tempest, and As You Like It, it belonged to the group of 18 plays preserved solely through the Folio effort.

Scholar Peter Blayney, in his authoritative The First Folio of Shakespeare (1991), notes that the King’s Men likely withheld certain high-value plays from print to maintain theatrical monopoly.

First Appearance in Print: The 1623 First Folio

Julius Caesar thus remained unprinted until the monumental 1623 collection. This delay proved fortunate: it avoided the textual corruption that plagued quarto versions of other plays, delivering to posterity one of the cleanest Shakespearean texts.

The Making of the 1623 First Folio

The Editors and Publishers

The First Folio was a posthumous tribute organized by two of Shakespeare’s fellow actors and shareholders in the King’s Men: John Heminges and Henry Condell. In their dedicatory epistle, they emphasized preserving Shakespeare’s works “cured, and perfect of their limbes” against the “stolne, and surreptitious copies” of quartos.

Printing was handled by Isaac Jaggard (son of William Jaggard, printer of some quartos) and Edward Blount, a respected stationer. Production spanned 1621–1623, involving multiple compositors whose varying habits have been meticulously analyzed by Charlton Hinman in The Printing and Proof-Reading of the First Folio of Shakespeare (1963).

The Folio’s Structure and Innovations

The volume revolutionized English drama:

- First collection devoted entirely to plays.

- Divided into Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies—categories we still use.

- Included 36 plays, preserving 18 never before printed (half of Shakespeare’s dramatic output).

Costing about £1 (equivalent to several weeks’ wages), it targeted wealthy patrons and institutions rather than the mass market.

Where Julius Caesar Fits in the Folio

Julius Caesar appears in the Tragedies section, positioned after Timon of Athens and before Macbeth. It spans pages 109–131 in the tragedies sequence (signatures gg1–hh6). The text is notably clean, with detailed stage directions suggesting derivation from a theatrical prompt-book.

The Textual Significance of the Folio Julius Caesar

Source of the Folio Text

Most scholars agree the printer’s copy was a high-quality scribal transcript or the theatre’s own prompt-book. Evidence includes:

- Abundant stage directions (e.g., “Enter Brutus in his Orchard,” precise entrances/exits).

- Minimal corruption: Fewer obvious errors than in many quarto-derived plays.

- Consistency in speech prefixes and lineation.

David Bevington, in his Cambridge edition, calls it “one of the best texts in the canon.”

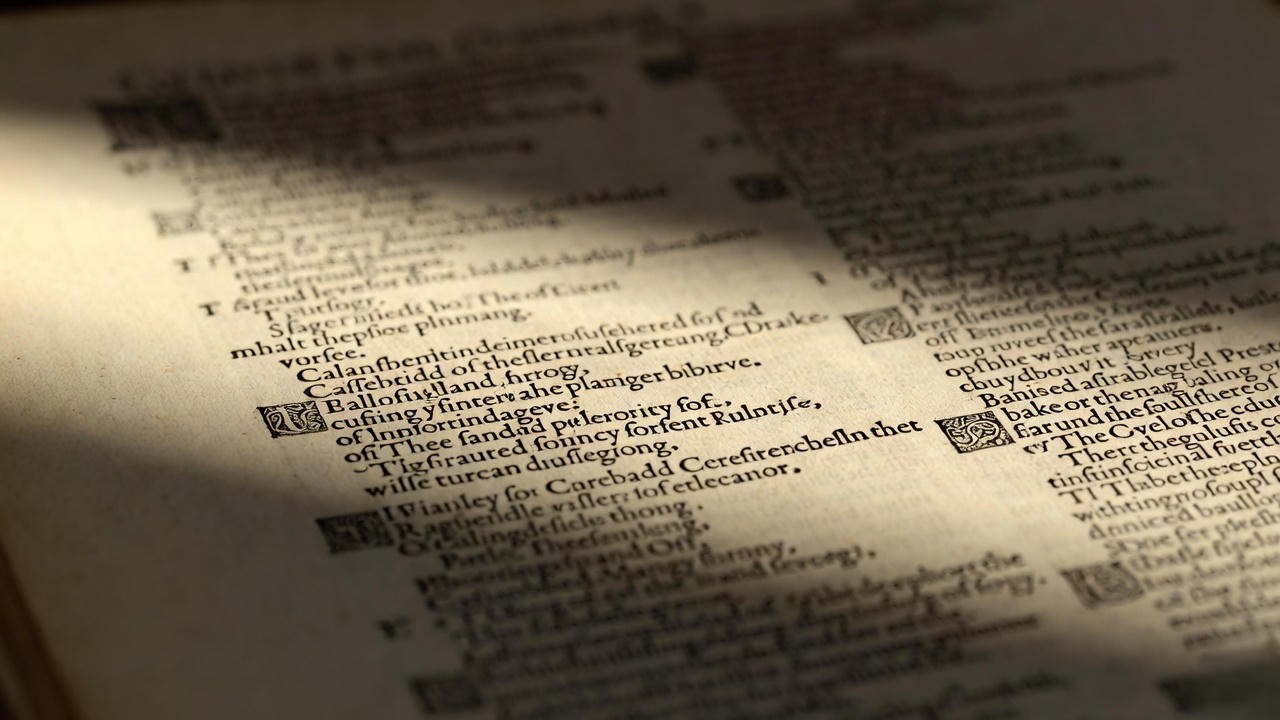

Key Features of the Original Printing

The 1623 text retains Elizabethan spelling and punctuation:

- Title: “The Tragedie of Ivlivs Cæsar”

- Light punctuation: Often only commas and periods, allowing flexible delivery.

- Verse/prose distinctions preserved with careful indentation.

Notable quirks include occasional “massed entries” (all characters listed at scene start) and Latin passages in Roman type.

Differences from Modern Editions

Modern editions introduce hundreds of changes:

- Act and scene divisions (absent in Folio; added by Nicholas Rowe in 1709).

- Modernized spelling and punctuation (affecting rhythm and emphasis).

- Emendations: e.g., Pope’s “sullens” for Folio’s “sullens” (modern “sulks”).

Studying the original printing reveals how editorial layers have shaped interpretation over centuries.

Legacy and Cultural Impact

Preservation of Shakespeare’s Work

Without the First Folio, Julius Caesar and 17 other plays might have vanished. Only about 235 copies survive today (of an estimated 750–1000 printed), with the Folger Shakespeare Library holding 82—the world’s largest collection.

Influence on Performance and Interpretation

The prompt-book origins inform modern staging:

- Detailed directions aid blocking and crowd management.

- Light punctuation allows actors interpretive freedom in delivery.

Directors like Orson Welles (1937 fascist-themed production) and recent RSC stagings often reference Folio authenticity.

Scholarly Importance in the 21st Century

Textual criticism continues: Hinman’s collations identified compositor habits; modern projects like the New Oxford Shakespeare re-evaluate sources. The Folio Julius Caesar remains the baseline for serious study.

How to Access and Study the Original Printing Today

Best Online Resources for Viewing the First Folio

High-quality digital facsimiles are freely available:

- Folger Shakespeare Library: Interactive bookreader with zoomable pages.

- Internet Shakespeare Editions (University of Victoria): Side-by-side old-spelling transcription and facsimiles.

- Bodleian Library First Folio: High-resolution images of their copy.

- British Library Treasures: Select pages with commentary.

- Meisei University (Japan): Complete scans of their copy.

These platforms allow page-by-page exploration of the original 1623 printing.

Tips for Reading the Original Text

- Familiarize yourself with Elizabethan typography: long “s” (ſ), “u/v” and “i/j” interchange.

- Read aloud: Light punctuation reflects spoken delivery.

- Compare editions: Use parallel-text resources to see editorial interventions.

- Start with the funeral orations (Folio pp. 118–120) to appreciate rhetorical flow.

Expert Insights and Further Reading

Renowned scholar Peter Blayney observes: “The Folio text of Julius Caesar is unusually good… probably set from an authoritative manuscript prepared in the playhouse.”

Textual editor David Daniell notes in his Arden Third Series introduction: “The 1623 text has authority from its closeness to performance.”

Recommended books:

- Charlton Hinman, The Printing and Proof-Reading of the First Folio (1963)

- Peter W.M. Blayney, The First Folio of Shakespeare (1991)

- Stanley Wells & Gary Taylor, William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion (1987)

- The Norton Facsimile: The First Folio of Shakespeare (2nd ed., 1996)

FAQs

Why is the First Folio text of Julius Caesar considered more reliable than later editions? It derives from sources close to Shakespeare’s company (likely a prompt-book), with minimal intervening corruption or editorial alteration.

Did Shakespeare oversee any printing of Julius Caesar? No—the play remained unprinted during his lifetime (died 1616). The Folio appeared in 1623.

How many changes occur between the Folio and modern versions? Hundreds, primarily in punctuation, spelling, lineation, and stage directions—changes that can significantly affect rhythm, pause, and interpretation.

Can I see the exact pages of Julius Caesar from 1623 online? Yes—high-resolution facsimiles are available via the Folger, Internet Shakespeare Editions, and Bodleian resources.

Why study the original printing? It connects us most directly to Shakespeare’s theatrical intentions, revealing how centuries of editing have shaped our reading and performance of the play.

Rediscovering Shakespeare’s Voice in the Original Printing

The 1623 First Folio’s Julius Caesar stands as one of the purest windows into Shakespeare’s art. Free from quarto corruption and early editorial overlay, it preserves the play as Shakespeare’s company knew it—vibrant, rhetorically charged, and theatrically alive. For anyone passionate about authentic texts, performance history, or the enduring power of Shakespeare’s language, exploring this original printing reveals depths that modern editions can only approximate.

Whether you’re a student preparing a paper, an actor seeking interpretive freedom, or a lifelong reader craving closeness to the Bard, the First Folio Julius Caesar awaits. Visit the digital resources today and experience the play as it first appeared in print—uncorrupted, immediate, and profoundly Shakespearean.