“That which we call a rose / By any other name would smell as sweet.” These immortal words from William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet (Act 2, Scene 2) capture the essence of the flower that has captivated poets, lovers, and warriors for centuries. Yet in Shakespeare’s England, the rose was far more than a sweet-smelling bloom—it was a potent symbol of beauty, love, transience, secrecy, and brutal political division. The gallic rose (Rosa gallica), also known as the French rose, rose of Provins, or Apothecary’s rose, stands at the heart of this symbolism. This ancient species, with its deep crimson-to-pink petals and intoxicating fragrance, is widely regarded as the botanical inspiration for the Red Rose of Lancaster, the emblem that defined one side of the Wars of the Roses—a conflict Shakespeare dramatized with unforgettable intensity in his history plays.

For readers passionate about Shakespeare, Tudor history, or heirloom gardening, understanding the gallic rose unlocks deeper layers in his works. Over 70 references to roses appear across his plays and sonnets, weaving themes of fleeting beauty, thorny love, and the fragility of power. By exploring the gallic rose’s ancient origins, its medicinal legacy, its role in the Wars of the Roses, and its echoes in Shakespeare’s language, this article offers fresh insights that enrich literary analysis and inspire modern appreciation. Whether you’re a literature student re-reading Henry VI, a gardener seeking authentic Tudor plants, or a history enthusiast tracing heraldic symbols, you’ll discover why this humble shrub shaped England’s national story—and Shakespeare’s enduring genius.

The Ancient Origins and Botanical Profile of the Gallic Rose

The gallic rose traces its roots to southern and central Europe, with early cultivation by the Greeks and Romans. Native to regions from France (hence “gallica,” from ancient Gaul) eastward to Turkey and the Caucasus, it was one of the first rose species domesticated in the West. Archaeological hints and historical records suggest cultivation as early as the 12th century BC in some Mediterranean contexts, though widespread European use surged after the Crusades (12th–13th centuries), when returning knights likely introduced refined forms from the East, including Persia.

By the Middle Ages, Rosa gallica had become a staple in monastic and noble gardens. Known as the Apothecary’s rose (Rosa gallica officinalis), it earned its name through practical utility in herbal medicine. Physicians and apothecaries prized its petals for remedies, distilling them into rosewater, conserves, and ointments. This variety, often called the Red Rose of Lancaster or Old Red Damask, featured semi-double to double blooms in rich crimson-pink shades—the closest medieval Europe came to true “red” in roses.

Botanically, Rosa gallica is a deciduous shrub forming dense patches through suckering. It typically grows 90–150 cm tall, with upright, thorny canes and rough, dark green foliage. Flowers appear once in early summer (June–July), single or semi-double, 5–8 cm across, with a powerful, spicy-sweet fragrance that lingers in the air. Unlike modern repeat-bloomers, it flowers profusely on old wood for one dramatic flush, then sets hips rich in vitamin C.

In modern gardens, Rosa gallica remains hardy (USDA Zones 4–8), thriving in full sun (at least 6 hours daily) and well-drained, loamy soil enriched with organic matter. It tolerates poor soils better than many hybrids but benefits from mulch to retain moisture and suppress weeds. Prune lightly after flowering to shape and remove dead wood—avoid heavy cuts, as blooms form on previous year’s growth. Disease resistance is generally good, though black spot can occur in humid conditions; good air circulation helps prevent issues.

This species is the genetic foundation for countless modern roses, contributing fragrance, form, and resilience to hybrids from damasks to hybrid teas.

The Gallic Rose as the Red Rose of Lancaster – Symbolism in the Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses (1455–1487) pitted the Houses of Lancaster and York against each other in a brutal struggle for England’s throne. While historical records show the red rose as Lancaster’s badge from the 14th century (adopted by John of Gaunt’s line), the dramatic opposition of red and white roses as central emblems was amplified in later chronicles—and immortalized by Shakespeare.

Historians debate the precise timing and prominence of rose badges during the actual wars; they shared space with suns, swans, and fetterlocks. Yet by the Tudor era, the motif had crystallized: the red rose for Lancaster, the white for York, and their union in the Tudor rose symbolizing peace under Henry VII after Bosworth Field (1485).

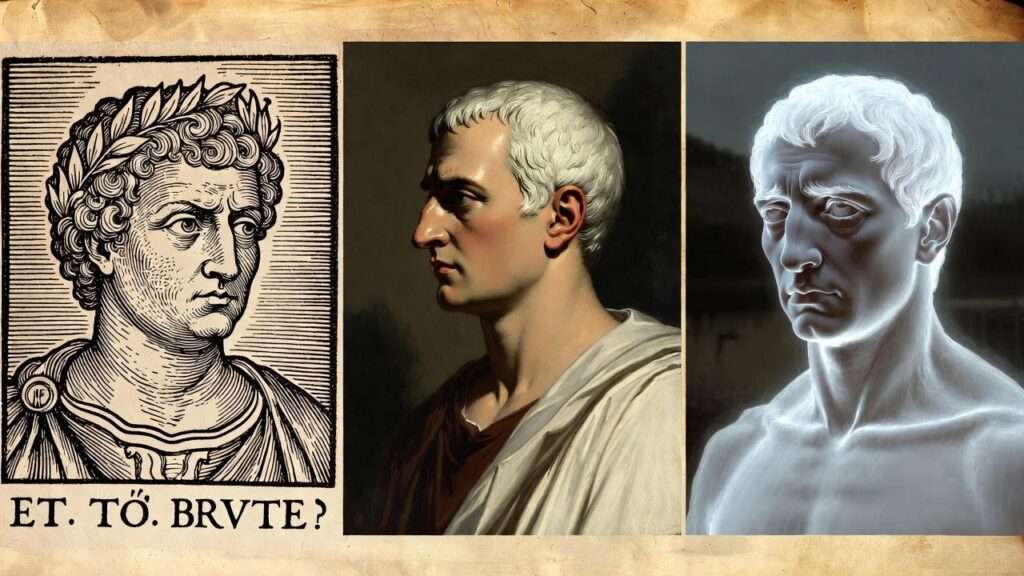

Shakespeare seized this symbolism in his Henry VI trilogy. The most famous scene occurs in Henry VI, Part 1, Act 2, Scene 4, set in the Temple Garden:

“I pluck a red rose from off this thorn withal… Let him that is a true-born gentleman And stands upon the honor of his birth If he suppose that I have pleaded truth From off this brier pluck a white rose with me.”

Nobles pluck roses to declare allegiance—Somerset and Suffolk choose red (Lancaster), Plantagenet and Warwick white (York)—turning a simple garden into a microcosm of civil war. Shakespeare uses the roses to foreshadow bloodshed, betrayal, and the fragility of loyalty. The red rose, deep and passionate, evokes Lancaster’s claim; its thorns mirror the conflict’s pain.

Experts widely identify Rosa gallica officinalis as the Red Rose of Lancaster. Its crimson-pink hue matched medieval perceptions of “red” (true scarlet roses arrived later from Asia). In contrast, the white rose aligned with Rosa alba or Rosa canina. This botanical link grounds Shakespeare’s metaphor in the living plants of Tudor England, where gallica roses bloomed in cottage plots, monastery herbals, and noble estates—exactly the world Shakespeare knew in Stratford and London.

Roses in Shakespeare’s Broader Works – Beyond the Wars

Shakespeare’s fascination with roses extends far beyond political drama. The flower appears over 70 times, more than any other, symbolizing beauty, love, transience, and mortality.

In the sonnets, roses embody ideal yet fleeting perfection. Sonnet 130 famously subverts convention: “I have seen roses damask’d, red and white,” contrasting the beloved’s natural charm against artificial ideals. Sonnet 54 praises inner truth: “The rose looks fair, but fairer we it deem / For that sweet odour which doth in it live.” Here, fragrance represents enduring virtue, distilled into poetry like perfume from petals.

Romantic plays abound with roses. In Romeo and Juliet, the famous line denies names’ power over essence, yet thorns remind us love’s dangers (“It pricks like thorn”). A Midsummer Night’s Dream mentions “musk-roses” and eglantine, evoking enchanted forests. Roses signify secrecy too (“sub rosa” tradition), fragility, and decay—canker in the bud mirroring hidden flaws.

Shakespeare likely encountered gallica roses daily in Tudor gardens. Stratford’s cottage plots and London’s herbalists grew them for medicine and scent. Estates featured formal borders where such heirlooms thrived, influencing his vivid floral imagery.

The Gallic Rose’s Medicinal and Cultural Legacy

From Apothecary Remedies to Modern Uses

The nickname “Apothecary’s rose” was not given lightly. For centuries, Rosa gallica was one of the most pharmacologically important roses in Europe. Its petals, hips, and even leaves were harvested for a wide array of remedies documented in medieval and Renaissance herbals.

John Gerard’s Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes (1597), a key text from Shakespeare’s lifetime, describes the “Red Rose of Provins” (a common name for Rosa gallica officinalis) as possessing “binding, cooling, and drying virtues.” Gerard notes its use in treating inflammations, fevers, headaches, and “fluxes of the belly.” Rose petals were boiled into syrups, distilled into rosewater (still a staple in Middle Eastern and Indian cuisine today), and candied into conserves. Rose oil, extracted through enfleurage or distillation, soothed skin ailments and served as a base for perfumes.

Nicholas Culpeper, in his 1653 Complete Herbal, echoes these uses and adds that the rose “strengthens the heart” and is “good against the trembling thereof.” In Shakespeare’s era, apothecaries in London and Stratford would have kept jars of dried gallica petals for compounding medicines, while households used rosewater for cooking, hygiene, and even as a mild antiseptic.

Today, Rosa gallica retains a niche but enthusiastic following in natural health and aromatherapy. Modern research has confirmed high levels of antioxidants (especially polyphenols and vitamin C in the hips), anti-inflammatory properties, and antimicrobial effects in rose extracts. The essential oil is still prized in high-end perfumery for its rich, honeyed, slightly spicy profile—often described as the quintessential “old rose” scent.

Enduring Influence in Literature and Culture

Beyond medicine, the gallic rose left an indelible mark on heraldry, national identity, and literature. After the Tudor victory at Bosworth, Henry VII combined the red and white roses into the Tudor rose, a symbol of reconciliation still used in British emblems today (most visibly on the royal coat of arms and Lancashire’s county flag).

In post-Shakespearean literature, the gallic rose’s deep color and fragrance inspired Romantic poets. John Keats, in “Ode on Melancholy,” evokes the “globed peonies” and roses that “burst the velvet of their buds,” imagery rooted in the same dramatic once-blooming habit that Shakespeare knew. The flower’s revival in the 19th and 20th centuries—thanks to collectors and breeders like David Austin—has ensured its continued presence in cottage and heritage gardens.

Growing Your Own Shakespeare-Inspired Gallic Rose Garden (Practical Tips)

Varieties to Consider

Several cultivars of Rosa gallica remain widely available and historically authentic:

- Rosa gallica officinalis (“Apothecary’s Rose” or “Red Rose of Lancaster”) — the classic semi-double crimson form.

- Rosa gallica ‘Versicolor’ (“Rosa Mundi”) — a striking striped pink-and-white sport, possibly known in Tudor times.

- Rosa gallica ‘Violacea’ — deep purple-crimson, very fragrant.

These heirloom roses are often sold by specialist nurseries such as David Austin Roses, Heirloom Roses, or British heritage suppliers.

Designing a Tudor-Style Border

To recreate the sensory experience Shakespeare would have known, plant gallica roses in a mixed border with companions he mentions elsewhere:

- Sweet violet (Viola odorata)

- Wild thyme (Thymus serpyllum)

- Eglantine or sweet briar (Rosa rubiginosa)

- Lavender, marjoram, and rosemary

Arrange in informal clusters rather than rigid rows—medieval and Tudor gardens favored naturalistic abundance. Use low box or germander edging for structure. Position the roses where their fragrance can drift on warm June evenings, just as it would have in Stratford-upon-Avon’s cottage gardens or the gardens of the Inns of Court.

Maintenance for an Authentic Feel

- Plant in autumn or early spring in well-drained soil (pH 6.0–7.0).

- Water deeply but infrequently once established; gallicas are drought-tolerant.

- Mulch annually with compost or well-rotted manure.

- Minimal pruning: remove dead wood and thin crowded canes after flowering.

- Expect one glorious flush in early summer, followed by attractive round hips that attract birds.

Gardening with gallica roses offers more than historical reenactment—it connects modern readers directly to the living imagery Shakespeare employed, turning abstract metaphor into tangible scent and color.

Expert Insights and Common Misconceptions

A persistent myth claims Shakespeare’s red rose was a modern hybrid tea. Botanical and horticultural historians, however, agree that no true scarlet rose existed in England before the late 18th century. Rosa gallica’s deep crimson-pink was the closest match, as confirmed by rose scholars such as Graham Stuart Thomas and Peter Beales.

Another misconception is that the Wars of the Roses were universally symbolized by roses during the actual conflict. Contemporary sources rarely mention rose badges; the motif gained prominence in Tudor propaganda and was dramatically amplified by Shakespeare for theatrical effect.

As enthusiasts of Shakespeare’s floral language often note, his roses are never generic. He distinguishes damask, musk, and wild varieties, showing keen observation of real plants. The gallic rose, with its medicinal pedigree and heraldic color, fits seamlessly into this precise botanical imagination.

The gallic rose is far more than a pretty flower in Shakespeare’s world—it is a living bridge between botany, medicine, politics, and poetry. From the ancient gardens of Gaul to the apothecary jars of Tudor London, from the thorny briers of the Temple Garden scene to the perfumed metaphors of the sonnets, Rosa gallica shaped the imagery that still moves readers four centuries later.

Shakespeare understood that roses are transient yet powerful: they bloom brilliantly, then fade, leaving fragrance and memory behind. In the same way, the gallic rose reminds us that true essence endures—beyond names, wars, or time.

Revisit Henry VI, Part 1 or Sonnet 130 with this knowledge, and the lines will resonate anew. Better yet, plant a gallica rose this autumn. When its first crimson blooms open next June, you will share a sensory experience with the playwright himself—one that no page can fully capture.

FAQs

What is the gallic rose? The gallic rose (Rosa gallica) is an ancient European rose species, also called the French rose, rose of Provins, or Apothecary’s rose. It produces fragrant, once-blooming crimson-pink flowers and is considered the likely botanical basis for the Red Rose of Lancaster.

Did Shakespeare mention Rosa gallica by name? No—he refers to roses generically or by type (damask, musk, eglantine). However, the gallic rose was the most common red-flowered rose in Tudor England and aligns closely with his symbolic and descriptive uses.

Which Shakespeare play features the red and white roses most prominently? Henry VI, Part 1, Act 2, Scene 4—the Temple Garden scene—where nobles pluck red and white roses to declare allegiance during the Wars of the Roses.

How can I grow Rosa gallica today? Choose a sunny spot with well-drained soil. Plant in autumn or spring, water regularly the first year, and prune lightly after flowering. It is hardy, low-maintenance, and highly fragrant—ideal for heritage or Shakespeare-themed gardens.