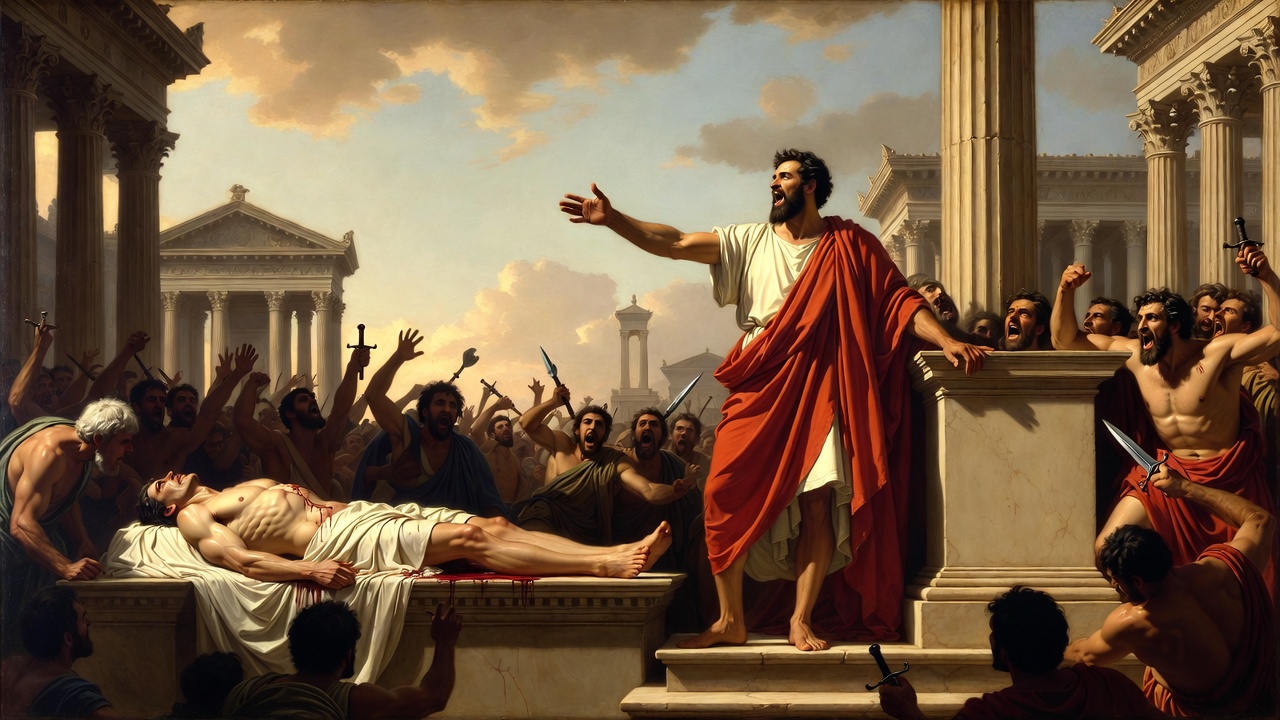

Imagine the Roman Forum on March 15, 44 BCE: chaos erupts as Julius Caesar lies dead, stabbed 23 times by senators he once called friends. His body, carried to the heart of the city, is placed on an impromptu pyre near the Regia. Mark Antony ascends the Rostra, delivers a masterful oration, and unleashes the fury of the mob. Flames consume the corpse; a comet blazes across the sky for days, interpreted by the people as Caesar’s soul ascending to join the gods. In Shakespeare’s immortal words from Julius Caesar (Act 3, Scene 2): “Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears; / I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him.”

This raw moment of grief, rage, and divine portent became the foundation for one of ancient Rome’s most enduring monuments: the Temple of Divine Julius (Aedes Divi Iulii), also known as the Temple of Caesar or the Temple of the Deified Julius. Built on the exact site of that cremation, it transformed a makeshift altar into a grand symbol of posthumous divinity—the first temple in Rome dedicated to a deified mortal. Completed and dedicated by Augustus in 29 BCE, the temple stood as powerful propaganda, linking the new princeps to his adoptive father while paving the way for the imperial cult.

For readers of Shakespeare, understanding this temple unlocks deeper layers in Julius Caesar. The play dramatizes ambition, betrayal, rhetoric, and the illusion of godlike power; the real temple shows how those themes played out in history. Augustus succeeded where Shakespeare’s Caesar faltered—immortalizing a man in stone and cult while consolidating an empire. This article explores the temple’s history, architecture, political significance, and its profound echoes in Shakespeare’s tragedy, offering insights that bridge ancient Rome and Elizabethan drama.

Historical Background – The Assassination, Deification, and Birth of a Cult

The path to the Temple of Divine Julius began with tragedy and opportunism.

The Ides of March and Caesar’s Cremation in the Forum

On the Ides of March (March 15, 44 BCE), conspirators led by Brutus and Cassius assassinated Julius Caesar in the Theatre of Pompey. His body was carried to the Forum, placed near the Regia (official residence of the Pontifex Maximus, a role Caesar held) and the Temple of Vesta. Antony’s funeral oration—dramatic in historical accounts by Appian and Dio Cassius—turned public sentiment against the assassins. The crowd built a pyre from wooden benches and shops; Caesar’s body burned amid riots. A comet (later called Caesar’s Comet or sidus Iulium) appeared during funeral games organized by Octavian (future Augustus), solidifying popular belief in Caesar’s divinity.

An altar and column were erected spontaneously at the cremation site, becoming a focal point for devotion and asylum-seekers.

Posthumous Deification – A Political Masterstroke

In 42 BCE, the Second Triumvirate (Octavian, Mark Antony, Lepidus) secured Senate approval for Caesar’s deification—the first for a Roman citizen. This elevated Caesar to Divus Iulius (“the Divine Julius”), establishing a precedent for the imperial cult. Temples, priests (flamines), and games followed. The decree included building a temple on the cremation site, replacing the makeshift memorials.

Ancient sources like Suetonius, Appian, and Dio Cassius describe this as both genuine piety and shrewd politics. Octavian, styling himself divi filius (“son of the divine”), gained legitimacy amid civil wars.

From Makeshift Altar to Grand Temple

Initial monuments were destroyed in 42 BCE by consul P. Cornelius Dolabella to curb unrest, but Octavian persisted. Construction likely intensified after Actium (31 BCE). Augustus claimed sole credit in his Res Gestae Divi Augusti (Monumentum Ancyranum): he built the aedem divi Iuli. Dedicated on August 18, 29 BCE, during his triple triumph over Antony and Cleopatra, the temple marked his consolidation of power.

Architecture and Design of the Temple of Divine Julius

The temple blended Hellenistic grandeur with Roman innovation.

Location and Layout in the Roman Forum

Positioned on the Forum’s east side, between the Regia, Temple of Vesta, and Basilica Aemilia, it dominated the southeastern quadrant. Its high podium (about 3.5 meters) featured lateral ramps leading to the Rostra Julia—a speaker’s platform adorned with ship prows from Actium, echoing the old Rostra.

A semicircular exedra at the front housed the altar marking Caesar’s pyre site.

Structural Features and Style

A prostyle temple (columns only at the front), its order remains debated—likely Ionic or Corinthian. A frontal staircase ascended to the cella. Inside stood a colossal veiled statue of Caesar as Pontifex Maximus, holding an augural staff, with a star on his forehead symbolizing the comet (per Pliny and Suetonius).

The podium incorporated the Rostra Julia; some scholars link it to the Porticus Iulia. A nearby Temple of the Comet Star may have complemented it.

Surviving Remains Today

By the late 15th century, marble was quarried for churches and palaces. Excavations in the 1950s revealed the podium’s concrete core, semicircular niche, and altar platform. Today, visitors see weathered tufa and brick remnants—a low mound with an altar-like structure where flowers are placed daily. It’s a pilgrimage site, especially on March 15 (Ides of March commemorations).

Augustus’ Motivations – Propaganda, Power, and Legacy

The construction of the Temple of Divine Julius was far more than an act of filial piety. For Octavian—soon to be Augustus—it represented one of the most brilliant pieces of political engineering in Roman history.

Consolidating Power Through Divinity

By completing and dedicating the temple in 29 BCE, Augustus publicly declared himself divi filius—son of the divine Julius. This title appeared on coins, inscriptions, and official documents from the 30s BCE onward. The temple physically anchored his claim to exceptional legitimacy: he was not merely Caesar’s heir but the son of a god. In a society still scarred by civil war, this divine lineage helped transform a young, relatively unknown aristocrat into the inevitable restorer of the Republic (a carefully crafted fiction).

The temple’s location in the Forum—Rome’s political and religious heart—was no accident. Every time senators, magistrates, or ordinary citizens passed its podium, they were reminded of Caesar’s apotheosis and Augustus’ connection to it.

The Imperial Cult’s Origins

The Temple of Divine Julius marks the formal beginning of the Roman imperial cult in the city itself. While Hellenistic rulers had long been worshipped as gods, and while Caesar had received extraordinary honors during his lifetime (including a statue in the Temple of Quirinus inscribed “To the Unconquered God”), posthumous deification of a Roman citizen was unprecedented. Augustus carefully calibrated this innovation: he refused divine honors for himself while alive in Rome, but allowed and encouraged them in the provinces. The precedent set by Divus Iulius made future emperors’ deification seem natural rather than revolutionary.

Priests known as flamines Divi Iulii were appointed (the first being Mark Antony, before his fallout with Octavian), and annual games (ludi) honored the deified Caesar. The cult spread rapidly across the empire, blending local religious traditions with Roman loyalty to the ruling house.

Political Symbolism vs. Genuine Devotion

Scholars continue to debate Augustus’ motives. Suetonius reports that Octavian was deeply devoted to his adoptive father’s memory, preserving his papers and honoring his will. Yet the timing of the temple’s dedication—during the triple triumph that celebrated victories over foreign enemies and fellow Romans—suggests calculated symbolism. The temple stood as visible proof that Caesar’s assassins had failed: the man they killed had become a god, and his heir now ruled supreme.

Modern historians such as Paul Zanker (in The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus) argue that the temple formed part of a broader visual propaganda program—alongside the Ara Pacis, Forum of Augustus, and statues of Divus Iulius—that reshaped Roman identity around the figure of Augustus as bringer of peace and restorer of ancestral values.

Echoes in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar – Bridging History and Drama

Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar (written c. 1599) draws heavily on Plutarch’s Lives and Appian’s Civil Wars, but the Temple of Divine Julius—though not mentioned explicitly in the play—casts a long shadow over its themes and ironies.

The Funeral Oration – From Forum Pyre to Stage

Shakespeare compresses and heightens the historical funeral into one of the most famous scenes in English literature. In Act 3, Scene 2, Antony speaks from the Rostra (in reality, the old Rostra stood nearby, but the new Rostra Julia would later be built as part of the temple complex). His speech—“Friends, Romans, countrymen…”—mirrors the rhetorical turning point described by ancient historians: Antony displays Caesar’s bloodied mantle, reads the will, and incites the mob to riot and burn the body.

Yet Shakespeare adds psychological depth absent from the sources. Antony feigns reluctance (“I am no orator, as Brutus is”), then systematically dismantles Brutus’ claim that Caesar was ambitious. The historical oration likely relied more on emotional appeals and the comet’s appearance; Shakespeare transforms it into a masterclass in manipulation, making the scene a study in demagoguery that resonates with any era of populist politics.

Standing today at the surviving altar of the Temple of Divine Julius, one can almost hear Antony’s voice echoing off the podium—because the stone beneath your feet is the literal stage where those events unfolded.

Themes of Deification and Mortal Hubris

The play repeatedly circles the question of whether a man can become godlike. Caesar refers to himself in the third person (“Caesar doth not wrong”), compares himself to the North Star, and dismisses omens and warnings. Cassius warns: “Why, man, he doth bestride the narrow world / Like a Colossus…” These lines gain added poignancy when we remember that, after his death, Caesar was placed among the gods, his statue crowned with a star, his temple rising where his body burned.

Shakespeare’s Caesar is flawed, deaf (literally and metaphorically), vain, and ambitious—qualities that make his assassination plausible. Yet the historical outcome subverts the tragedy: the man the conspirators killed to save the Republic became divine, and the Republic itself gave way to autocracy under his heir. The temple stands as the silent rebuttal to Brutus’ idealism.

Legacy, Power, and Betrayal Parallels

Brutus believes that killing Caesar will restore liberty; instead, it unleashes chaos and paves the way for Augustus. The temple symbolizes the ultimate failure of the conspiracy: Caesar’s legacy not only survives but is magnified into divinity. Shakespeare’s audience—living under Elizabeth I, who carefully cultivated her own quasi-divine image—would have recognized the tension between republican ideals and monarchical reality.

In this sense, the Temple of Divine Julius completes the story Shakespeare leaves unfinished. The play ends with the triumph of Octavian (implied in the final lines about “the spirit of Caesar” ranging for revenge), but the temple shows how that spirit was literally enshrined in marble and worshipped for centuries.

Why This Matters for Modern Readers

For anyone studying or teaching Julius Caesar, knowledge of the temple transforms the text from a timeless meditation on power into a historically grounded commentary. It reveals Shakespeare’s subtle awareness of how rhetoric, memory, and monumental propaganda shape political reality—lessons that remain urgently relevant in an age of charismatic leaders, media manipulation, and contested legacies.

Visiting the Temple Today – Practical Guide and Reflections

The Temple of Divine Julius lies in the eastern Roman Forum, easily accessible via the main entrance near the Arch of Titus or the Via dei Fori Imperiali. Look for the low, semicircular brick and concrete structure with a simple altar platform—often adorned with fresh flowers left by visitors even today.

Best viewing comes early in the morning or late afternoon when crowds thin and the light highlights the podium’s curves. Stand at the altar and face west toward the Capitoline Hill: you occupy roughly the same spot where Antony spoke and where Caesar’s body burned.

For Shakespeare enthusiasts, I recommend reading Act 3, Scene 2 aloud while standing there. The acoustics are surprisingly good, and the physical immediacy of the place deepens the emotional impact of the words.

Nearby sites worth visiting include:

- The Regia (Caesar’s official residence as Pontifex Maximus)

- The Temple of Vesta

- The Curia Julia (rebuilt by Augustus)

- The Arch of Augustus (fragments visible near the temple)

Entry to the Forum is included with the Colosseum–Roman Forum–Palatine Hill combined ticket. Allow at least two hours to appreciate the temple in context.

A Monument to Ambition and Immortality

The Temple of Divine Julius is more than ruins in the Forum. It is the physical embodiment of Augustus’ greatest victory: the transformation of a murdered dictator into an eternal god, and of a fractured Republic into a stable autocracy masked as restoration. Flowers placed on its altar nearly 2,100 years later prove that Caesar’s star still shines.

Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar asks whether such ambition is noble or dangerous, whether rhetoric can justify betrayal, whether men should reach for divinity. The temple answers with stone certainty: ambition can succeed, rhetoric can reshape memory, and mortals can indeed become gods—at least in the eyes of those who come after.

Next time you read the play or walk the Forum, pause at that humble altar. Listen for Antony’s voice, see the comet in your mind’s eye, and remember: history and literature are not separate. They echo each other across millennia.

Frequently Asked Questions

Where is the Temple of Divine Julius located? In the Roman Forum, on the east side near the Regia and Temple of Vesta. GPS coordinates: approximately 41.8920° N, 12.4855° E.

Was Julius Caesar actually buried in the temple? No. Roman custom was cremation; his ashes were likely placed in the family tomb on the Via Appia. The temple altar marks the site of the funeral pyre and became a symbolic “grave.”

How does the temple relate to Shakespeare’s play? The play’s funeral oration and themes of deification, ambition, and legacy directly parallel the historical events commemorated by the temple. Understanding the real site enriches interpretation of the drama.

Why do people still leave flowers at the altar today? The spot has remained a site of popular veneration since 44 BCE. Visitors—especially on the Ides of March—honor Caesar as a symbol of genius, tragedy, or resistance to tyranny.