Imagine standing in the bustling yard of the Globe Theatre in 1601, shoulder to shoulder with merchants, laborers, and nobles, as the actor playing Hamlet steps forward, locking eyes with the crowd. “To be or not to be,” he begins, and the audience—rowdy, vocal, and utterly engaged—leans in, some shouting encouragement, others jeering. This vibrant interplay, the role of audience interaction in Shakespearean theatre, wasn’t just a backdrop; it was the heartbeat of the performance. Elizabethan audiences didn’t just watch plays—they shaped them, transforming each show into a dynamic, communal event. Why does this matter today? Understanding the role of audience interaction in Shakespearean theatre reveals the genius behind his enduring works and offers timeless lessons for modern performers, scholars, and theatre enthusiasts seeking to recapture that electric connection. This article explores how audience engagement turned passive spectators into active participants, creating unforgettable performances that still resonate centuries later.

The Historical Context of Shakespearean Theatre

The Elizabethan Theatre Environment

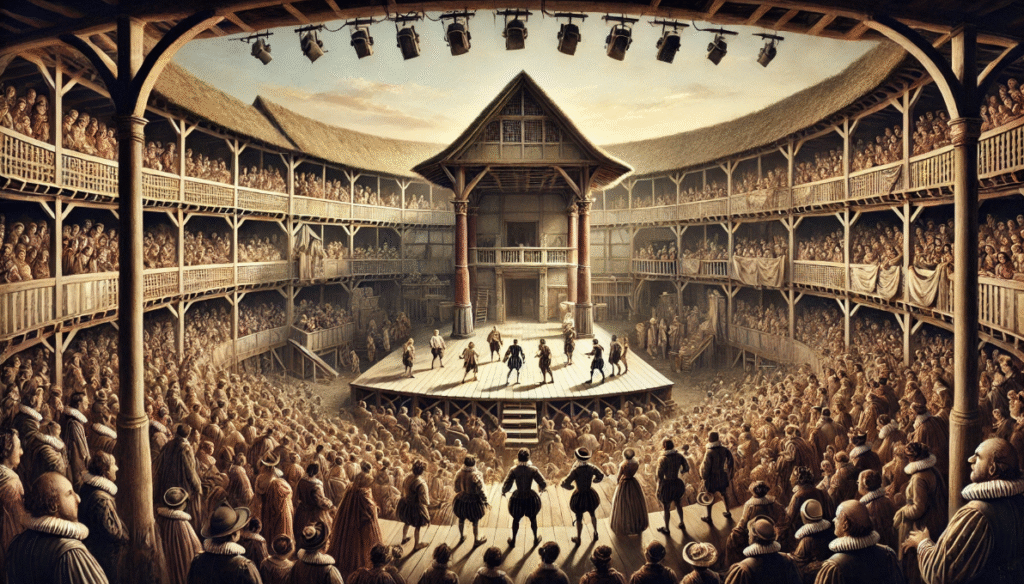

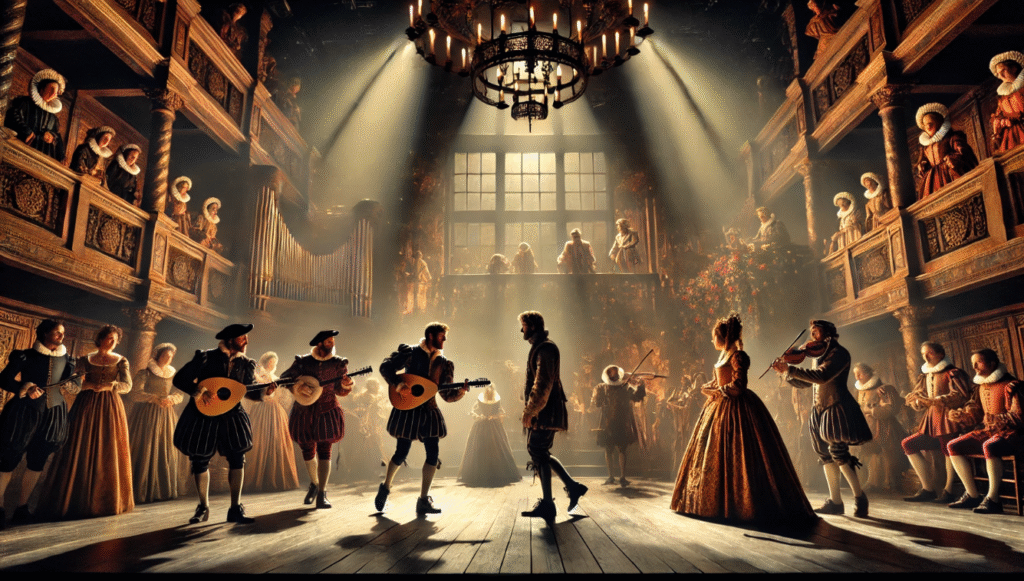

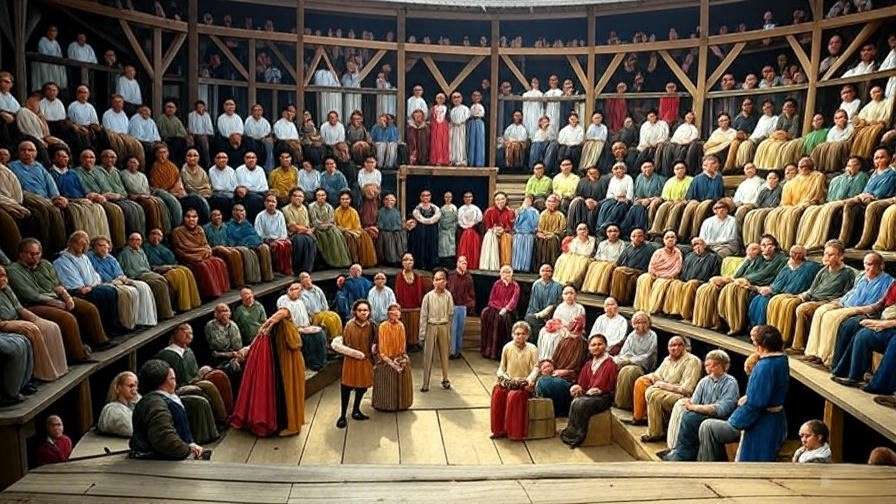

In Elizabethan England, theatres like the Globe and Blackfriars were far from the hushed, formal venues we imagine today. These open-air or candlelit spaces buzzed with energy, hosting a diverse crowd from all walks of life. Groundlings—working-class spectators—stood in the pit for a penny, while wealthier patrons sat in tiered galleries. The absence of advanced stage technology, like electric lighting or amplified sound, meant actors relied heavily on the audience’s energy to amplify the atmosphere. As theatre historian Andrew Gurr notes in Playgoing in Shakespeare’s London, the Globe’s open structure made audiences “part of the spectacle,” their reactions shaping the performance’s rhythm and intensity.

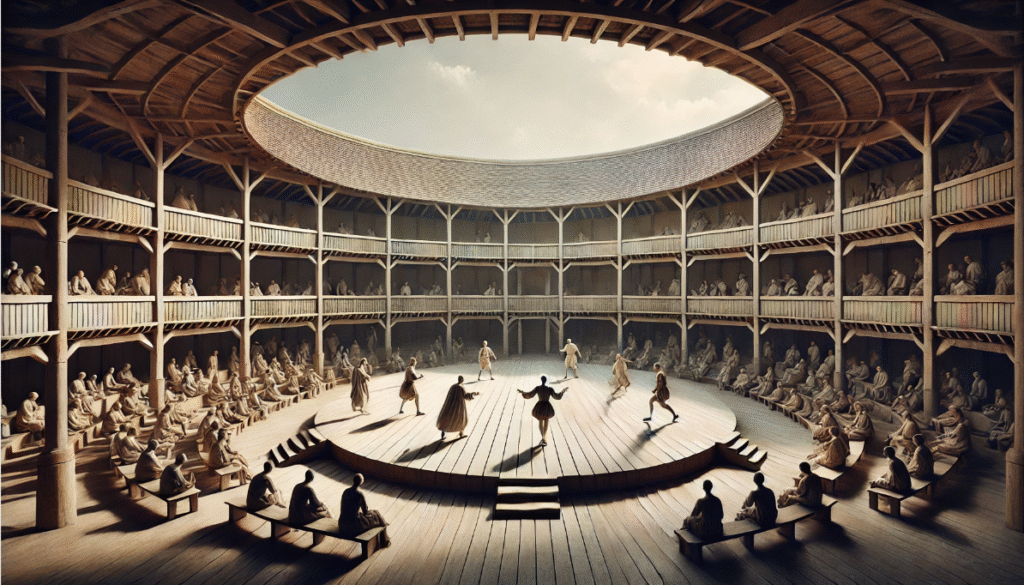

The physical layout of these theatres fostered intimacy. The thrust stage jutted into the audience, placing actors within arm’s reach of spectators. This proximity encouraged direct engagement—actors could hear laughter, heckling, or gasps and adjust their delivery on the fly. Unlike modern proscenium stages, Elizabethan theatres blurred the line between performer and audience, creating a shared space where every shout or cheer became part of the show.

Audience Composition and Expectations

Elizabethan audiences were a vibrant mix of social classes, each bringing distinct expectations. Groundlings craved action, humor, and spectacle, while educated elites appreciated poetic language and philosophical depth. Shakespeare, a master of balance, crafted plays that appealed to both. For instance, A Midsummer Night’s Dream delighted groundlings with Bottom’s slapstick antics while engaging scholars with its lyrical exploration of love and illusion.

Audience behavior was far from passive. Spectators ate, drank, and conversed during performances, sometimes shouting at actors or throwing fruit at unpopular characters. Historical accounts, like those from diarist John Manningham, describe audiences roaring with laughter during a 1602 performance of Twelfth Night, likely spurring the actors to lean into comedic moments. This lively atmosphere meant actors had to be nimble, responding to the crowd’s mood to keep their attention.

The Mechanics of Audience Interaction in Shakespeare’s Plays

Direct Address and Soliloquies

Shakespeare’s use of soliloquies and asides was a masterclass in audience engagement. These devices invited spectators into the characters’ inner worlds, creating a sense of intimacy. In Hamlet, the titular character’s “To be or not to be” soliloquy isn’t just a meditation on life and death—it’s a direct conversation with the audience, inviting them to ponder alongside him. Actors often paused for reactions, using cheers or silence to gauge the crowd’s mood and adjust their performance.

Asides, like Iago’s scheming monologues in Othello, further broke the barrier between stage and audience. By confiding in spectators, Iago made them complicit in his treachery, heightening emotional investment. Theatre scholar Stephen Greenblatt, in Shakespearean Negotiations, argues that these moments “transformed audiences into active participants,” blurring the line between observer and collaborator. For modern performers, practicing dynamic delivery—varying tone or pace based on audience reactions—can recreate this connection.

Breaking the Fourth Wall

Shakespeare frequently broke the fourth wall to engage audiences directly. In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Puck’s closing speech addresses spectators as “friends,” asking for their applause to “mend” the play’s flaws. This acknowledgment fostered a sense of community, making audiences feel like co-creators of the theatrical experience. Similarly, in As You Like It, Rosalind’s epilogue playfully teases the audience, inviting women to applaud and men to woo her, creating a playful rapport.

This technique wasn’t just theatrical flair; it was strategic. By addressing the audience, actors could gauge reactions and adapt, ensuring the performance resonated. Modern productions often struggle to replicate this spontaneity, but directors like Emma Rice have used direct address to recapture that Elizabethan energy, as seen in her immersive Globe productions.

Improvisation and Audience-Driven Performances

Improvisation was a hallmark of Shakespearean theatre, particularly in comedic roles. Clowns like Will Kemp, who played characters like Dogberry in Much Ado About Nothing, were known for ad-libbing based on audience reactions. If the crowd roared at a jest, Kemp might extend the bit; if they grew restless, he’d shift gears. Historical records, such as those in Tiffany Stern’s Documents of Performance, suggest that Kemp’s improvised jigs—lively dances performed post-play—were often tailored to the audience’s energy, ensuring a rousing finale.

In Twelfth Night, the clown Feste’s songs and banter likely varied nightly, responding to the crowd’s mood. This flexibility made each performance unique, a testament to the collaborative dynamic between actors and audience. Modern improv troupes, like those at the Upright Citizens Brigade, draw on similar principles, adapting to audience laughter or silence to shape the show.

The Role of Audience Interaction in Shaping Playwrighting

Shakespeare’s Adaptation to Audience Feedback

Shakespeare’s genius lay not only in his poetic mastery but also in his ability to adapt to audience preferences, ensuring his plays resonated with diverse crowds. Elizabethan theatre was a commercial enterprise, and playwrights like Shakespeare relied on ticket sales to thrive. Audience reactions—whether raucous cheers or restless murmurs—directly influenced his writing. For example, Titus Andronicus, with its graphic violence and sensational plot, catered to groundlings’ appetite for spectacle, while Hamlet leaned into philosophical depth to satisfy educated patrons. Theatre historian Tiffany Stern, in Making Shakespeare, notes that playwrights often revised scripts based on audience response, tweaking scenes to amplify popular elements or clarify confusing ones.

This adaptability is evident in Shakespeare’s evolution as a playwright. Early works like The Comedy of Errors leaned heavily on slapstick and farce, likely in response to groundling enthusiasm. As his career progressed, plays like King Lear balanced raw emotional intensity with crowd-pleasing elements like storms and battles. Shakespeare’s ability to read the room—quite literally—allowed him to craft works that were both artistic and commercially viable, a balance that modern playwrights still strive to achieve.

The Collaborative Nature of Performance

Audience interaction in Shakespearean theatre wasn’t just a feature; it was a form of collaboration that shaped the performance’s tone and pacing. Actors relied on crowd reactions to gauge whether a tragic moment landed or a comic bit needed more energy. This dynamic created a feedback loop where spectators were as much a part of the storytelling as the performers. For instance, in Macbeth, the witches’ scenes likely elicited gasps or shouts from superstitious audiences, prompting actors to heighten their eerie delivery.

Shakespeare’s understanding of this collaboration informed his writing. He embedded opportunities for audience engagement—such as comic interludes or dramatic pauses—knowing they would amplify the play’s impact. Scholar Stephen Greenblatt highlights in Will in the World how Shakespeare’s sensitivity to audience psychology allowed him to craft characters whose emotional complexity mirrored the crowd’s reactions. This collaborative spirit made every performance a unique, living event, a quality that modern theatre companies strive to recapture through interactive staging.

The Social and Cultural Impact of Audience Engagement

Theatre as a Social Mirror

Elizabethan theatre was a microcosm of society, and audience interaction reflected the era’s social and political dynamics. Plays like Richard III invited spectators to engage with contemporary issues, such as power struggles or tyranny, through their reactions. A jeer at Richard’s villainy or applause for Richmond’s victory wasn’t just theatrical—it was a public expression of sentiment in a time when open political discourse was risky. Historical accounts, such as those preserved in the Folger Shakespeare Library, describe audiences at Henry V cheering patriotic speeches, reflecting England’s national pride during wartime.

This social mirroring extended to class dynamics. Groundlings and nobles shared the same space, their reactions revealing tensions or unity. For example, in Coriolanus, the crowd’s response to the plebeians’ rebellion likely varied by social class, with groundlings cheering the uprising and elites shifting uncomfortably. Shakespeare used these reactions to refine his commentary, making his plays a dialogue with society itself.

Building Community Through Shared Experience

In an era without mass media, theatre was a communal hub where people gathered to laugh, cry, and debate. Audience interaction fostered a sense of shared identity, as spectators collectively responded to the story unfolding before them. The Globe’s open-air setting, with its diverse crowd, amplified this sense of community. When audiences laughed at Falstaff’s antics in Henry IV or wept at Ophelia’s death in Hamlet, they did so together, creating a shared emotional journey.

This communal aspect made Shakespeare’s theatre a cultural touchstone. As theatre scholar Emma Smith notes in This Is Shakespeare, the participatory nature of performances allowed audiences to feel ownership over the stories, strengthening their cultural impact. Modern theatre groups can recreate this by encouraging audience participation, such as call-and-response or post-show discussions, to foster a similar sense of connection.

Audience Interaction in Modern Shakespearean Productions

Recreating Elizabethan Engagement

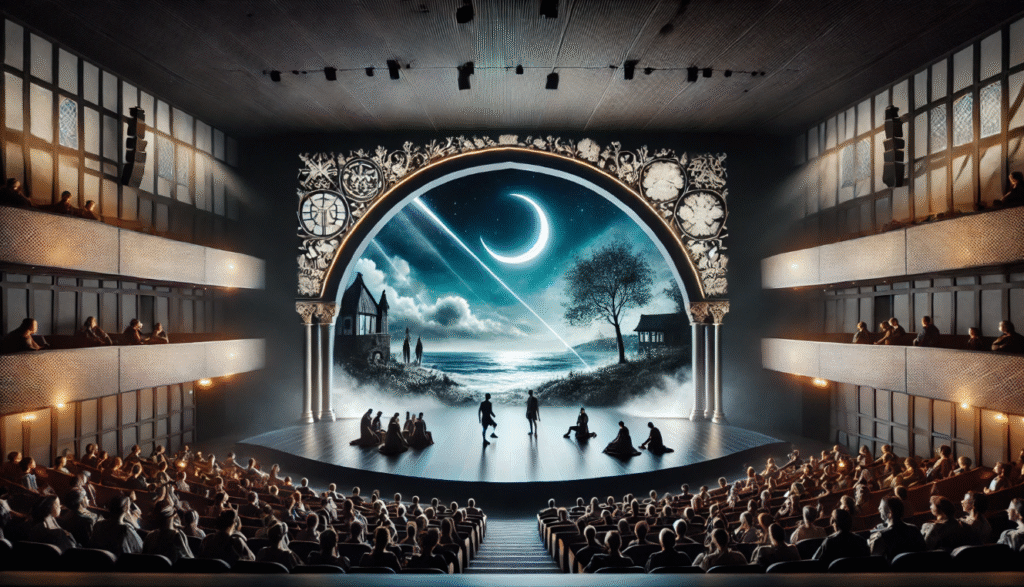

Modern productions, particularly at venues like the reconstructed Shakespeare’s Globe in London, strive to recapture the interactive spirit of Elizabethan theatre. The Globe’s open-air stage and standing yard mimic the original, encouraging audiences to cheer or heckle as their predecessors did. Director Mark Rylance, during his tenure at the Globe, embraced this dynamic, often pausing for audience reactions during performances of Twelfth Night or Richard III. These productions demonstrate how modern actors can use crowd energy to enhance authenticity and engagement.

Techniques like open-air staging, minimal sets, and direct address help recreate the Elizabethan experience. For example, the Globe’s 2019 production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream invited audience members to join in Puck’s final speech, blurring the line between performer and spectator. Such approaches not only honor historical practices but also make Shakespeare accessible to new generations.

Challenges and Opportunities

Engaging modern audiences, accustomed to passive entertainment like films or streaming, poses challenges. Today’s spectators often expect polished, predictable experiences, making it harder to replicate the spontaneity of Elizabethan crowds. However, innovative directors are finding ways to bridge this gap. Immersive theatre companies, like Punch drunk, draw on Shakespearean principles by placing audiences in the action, while digital platforms like Zoom have enabled virtual performances where viewers comment in real-time, echoing historical interactivity.

Director Emma Rice, formerly of the Globe, has championed this approach, using music, dance, and audience participation to make Shakespeare’s plays feel alive. Her 2016 production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream incorporated pop songs and crowd interaction, proving that Elizabethan techniques can resonate today. Theatre educators can adopt similar strategies, using workshops to teach actors how to respond to audience cues dynamically.

The role of audience interaction in Shakespearean theatre was more than a performance quirk—it was the heartbeat that shaped unforgettable experiences and cemented his legacy. From the roaring Globe crowds to the collaborative spirit that influenced his writing, this dynamic turned spectators into co-creators. Today, its lessons inspire modern productions, offering a bridge between past and present for performers, scholars, and lovers of the arts. We invite you to attend an interactive Shakespeare performance near you or share your own experiences in the comments, keeping this tradition alive.

H2: FAQs

-

What made Elizabethan audiences so interactive?

-

The informal setting of open-air theatres, a diverse social mix, and the absence of modern etiquette encouraged lively participation, making every performance unique.

-

-

How did Shakespeare use audience reactions?

-

He employed soliloquies, asides, and improvisation, allowing actors to adapt pacing and emphasis based on cheers, jeers, or silence.

-

-

Can modern productions replicate this interaction?

-

Yes, with success at the reconstructed Globe using open staging, though challenges remain with passive modern audiences, addressed by immersive techniques.

-

-

Why is this important for understanding Shakespeare?

-

It highlights his audience-centric craft, showing how interaction shaped his plays and their lasting cultural impact.

-