Picture the stage: a lone figure, Macbeth, stands frozen, his eyes locked on a spectral dagger floating before him. “Is this a dagger which I see before me?” he whispers, his voice trembling with ambition and dread. In this moment, the use of props to enhance dramatic effect in Shakespeare’s plays transforms a simple object into a haunting symbol of guilt and fate. In the bare Elizabethan theaters, where lavish sets were absent, props like daggers, skulls, and handkerchiefs carried immense weight, weaving emotion, symbolism, and action into unforgettable scenes. This article explores how these objects amplify drama, offering insights for theater enthusiasts, students, and scholars eager to uncover the magic behind Shakespeare’s staging. From iconic tragedies to lively comedies, we’ll delve into the power of props and their enduring impact, providing practical applications for modern theater and education.

The Role of Props in Elizabethan Theater

Historical Context of Minimalist Staging

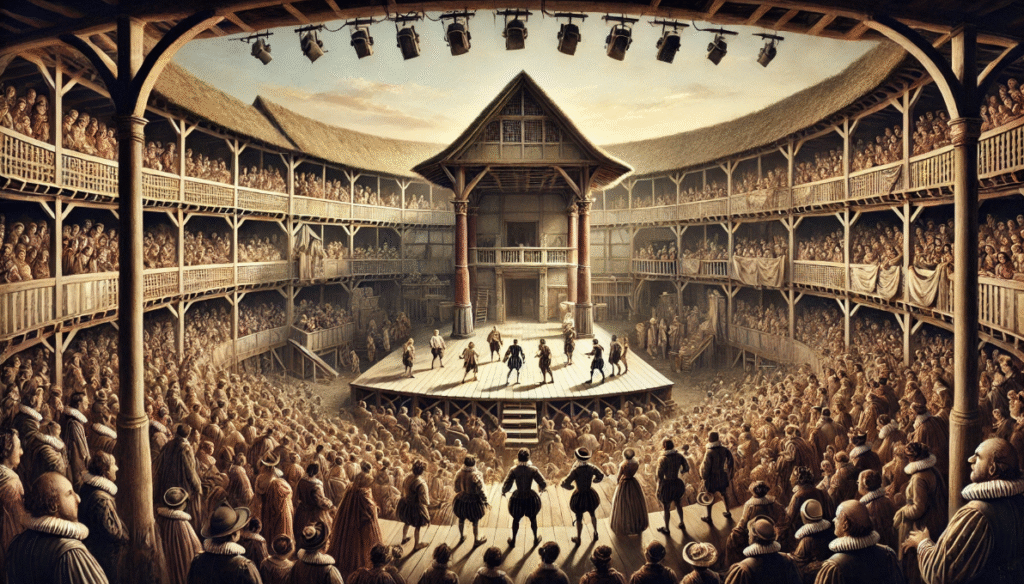

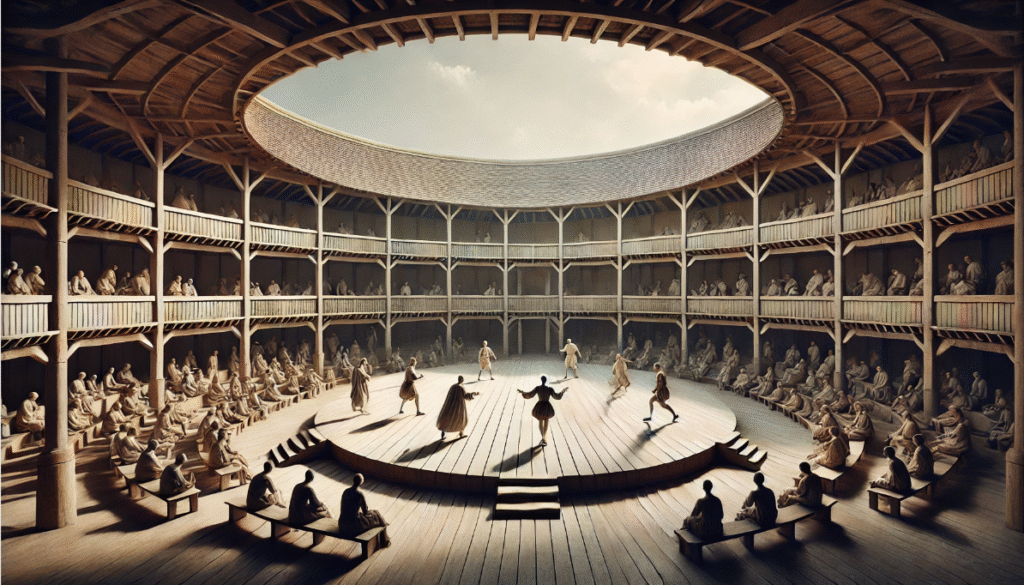

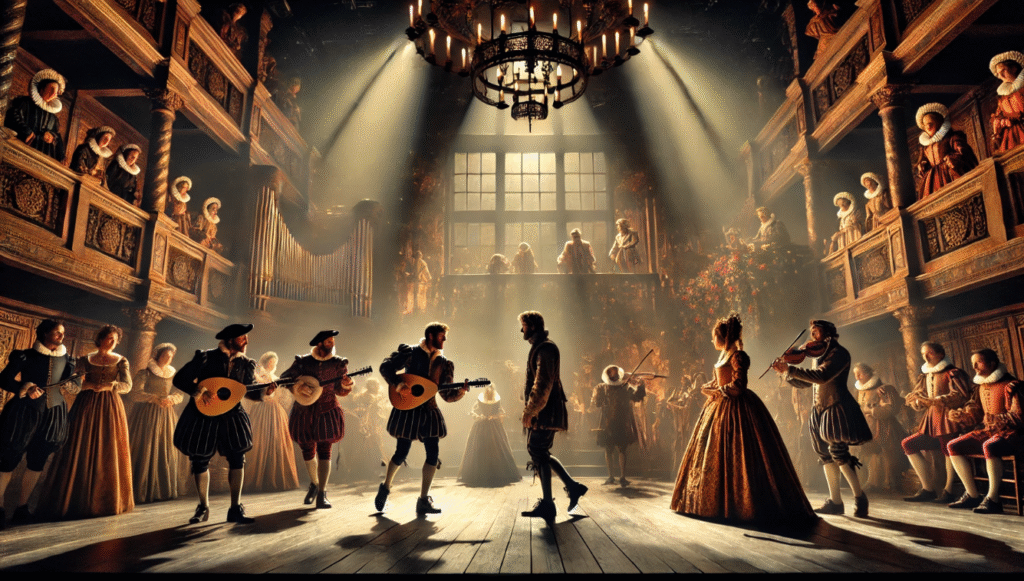

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Elizabethan theaters like the Globe operated with minimal scenery. Unlike today’s high-tech productions, stages were sparse, often just a wooden platform with a trapdoor or balcony. Props became the backbone of storytelling, transforming empty spaces into battlefields, courts, or forests. According to theater historian Andrew Gurr, props were “the visual shorthand of the Elizabethan stage,” signaling settings and themes with remarkable efficiency (Gurr, The Shakespearean Stage). A simple table could denote a royal banquet, while a sword might evoke a duel or a kingdom’s unrest. This minimalist approach forced playwrights like Shakespeare to rely on props to enhance dramatic effect, making them indispensable to the audience’s imagination.

The use of props was not just practical but strategic. With no curtains or scene changes, props provided visual cues to shift locations or moods. For instance, a throne instantly signified a royal court, while a lantern could suggest a nighttime escapade. This economy of staging allowed Shakespeare to craft complex narratives without elaborate backdrops, relying on the audience’s willingness to “piece out our imperfections with your thoughts,” as the Chorus in Henry V urges.

Why Props Mattered to Shakespeare’s Audiences

For Elizabethan audiences, props were more than stage dressing—they were gateways to meaning. A crown, a letter, or a blood-soaked cloth carried cultural and emotional weight, resonating with a diverse crowd of groundlings and nobles. Props signaled character status (e.g., a king’s scepter), advanced plots (e.g., a forged letter), or underscored themes like mortality or betrayal. Their tangible presence bridged the gap between the stage and the audience’s imagination, making abstract concepts vivid and relatable.

Consider the cultural context: Elizabethan England was steeped in symbolism, from heraldry to religious iconography. Audiences were adept at reading objects as metaphors. A prop like a ring in The Merchant of Venice wasn’t just jewelry—it symbolized trust, love, or deception, depending on the scene. This shared visual language allowed Shakespeare to craft layered narratives that spoke to both the educated and the illiterate, ensuring his plays’ broad appeal.

How Props Amplify Dramatic Effect in Shakespeare’s Plays

Symbolism and Emotional Resonance

Props in Shakespeare’s plays often carry profound symbolic weight, deepening the audience’s emotional connection to the story. The use of props to enhance dramatic effect in Shakespeare’s plays lies in their ability to embody abstract themes in tangible form. Take the handkerchief in Othello, a seemingly trivial object that becomes a devastating symbol of love, trust, and betrayal. When Othello gives it to Desdemona as a token of devotion, its loss—manipulated by Iago—triggers a cascade of jealousy and tragedy. Literary scholar Stephen Greenblatt notes that the handkerchief’s “fragile materiality” mirrors the fragility of human relationships, amplifying the play’s emotional stakes (Greenblatt, Will in the World).

This symbolic power extends across genres. In Romeo and Juliet, the vial of poison is not just a plot device but a chilling emblem of desperation and doomed love. Its presence on stage heightens the tension, as audiences anticipate its fatal role. Directors can amplify this effect in modern productions by emphasizing a prop’s visual impact—perhaps lighting the vial to glow ominously or staging it prominently during soliloquies.

Advancing Plot and Conflict

Props often serve as catalysts, propelling the narrative forward and intensifying conflict. In Hamlet, the poisoned chalice is a pivotal prop that seals the tragic climax. As Gertrude drinks from it unknowingly, the audience feels the weight of inevitability, a testament to Shakespeare’s mastery of dramatic pacing. The chalice’s presence transforms a courtly scene into a deadly tableau, showcasing how props can shift a play’s trajectory in an instant.

Similarly, in Julius Caesar, the bloodied daggers of the conspirators are not mere weapons but agents of chaos. Their display after Caesar’s assassination underscores the brutality and moral ambiguity of the act, driving the plot toward civil war. These examples highlight how props are not passive objects but active participants in the drama, shaping the story’s momentum.

Enhancing Character Development

Props also reveal character depth, offering insights into motivations and transformations. In Hamlet, Yorick’s skull is a profound prop that prompts the prince’s meditation on mortality: “Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him, Horatio.” Holding the skull, Hamlet confronts the inevitability of death, a moment that crystallizes his philosophical evolution. The prop grounds this introspection in a physical reality, making his existential crisis palpable for the audience.

In King Lear, the crown—whether worn or divided—reflects Lear’s shifting identity from king to broken man. As he removes or mishandles it, the prop mirrors his loss of authority and descent into madness. Actors can use such props to enhance performance authenticity, physically engaging with them to convey emotional shifts. For instance, a trembling hand clutching a crown can visually underscore a character’s vulnerability.

Iconic Props in Shakespeare’s Tragedies

The Dagger in Macbeth

Few props are as iconic as the dagger in Macbeth. In the famous soliloquy, “Is this a dagger which I see before me?”, Macbeth’s vision of a floating blade encapsulates his inner turmoil. The use of props to enhance dramatic effect in Shakespeare’s plays is nowhere clearer than in this moment, where the dagger—real or imagined—foreshadows murder and guilt. On stage, directors often use lighting or positioning to make the dagger appear ethereal, heightening its psychological impact. For example, in Roman Polanski’s 1971 film adaptation, the dagger glimmers faintly, blurring the line between hallucination and reality.

The dagger’s role extends beyond the soliloquy. Once Macbeth commits the murder, real daggers become symbols of his irreversible choice, their bloodied blades haunting him and Lady Macbeth. This prop’s versatility—shifting from vision to reality—demonstrates Shakespeare’s genius in using objects to mirror a character’s psyche.

The Handkerchief in Othello

In Othello, the handkerchief is a masterclass in prop-driven tragedy. Given by Othello to Desdemona as a token of love, it becomes a weapon in Iago’s hands, fueling Othello’s jealousy. Its delicate embroidery, described as having “magic “‘in the web,” carries cultural weight, possibly evoking exotic or mystical connotations for Elizabethan audiences. Scholar Barbara Everett argues that the handkerchief’s “smallness” belies its monumental role, as its loss unravels the entire marriage (Everett, Young Hamlet).

On stage, the handkerchief’s physical presence—passed, dropped, or stolen—creates tension. Modern productions might emphasize its fragility with close-up camera work in film or careful blocking in theater, ensuring the audience feels its significance. This prop’s journey from love token to tragic catalyst underscores how the use of props to enhance dramatic effect in Shakespeare’s plays drives narrative and emotion.

The Skull in Hamlet

Yorick’s skull in Hamlet is one of Shakespeare’s most enduring images. In the graveyard scene, Hamlet’s encounter with the skull prompts a meditation on death: “Where be your gibes now?” The prop embodies the memento mori tradition, reminding audiences of mortality’s universality. Its stark, physical presence—often a real or realistic skull on stage—grounds Hamlet’s philosophical musings, making them accessible and visceral.

Directors amplify this effect through staging. In a 2009 RSC production, David Tennant’s Hamlet held the skull aloft, his face illuminated to highlight his grief and wonder. Such choices showcase how props can anchor profound themes, creating moments that linger with audiences long after the curtain falls.

Iconic Props in Shakespeare’s Comedies and Histories

Comic Props for Humor and Irony

In Shakespeare’s comedies, props often serve as sources of humor and irony, driving the playful misunderstandings that define the genre. The use of props to enhance dramatic effect in Shakespeare’s plays shines in works like A Midsummer Night’s Dream, where the love potion, applied via a flower, sparks chaos among the lovers. This prop, described as having “charmed” properties, transforms relationships with its misapplication, creating comedic entanglements that delight audiences. The flower’s physical presence—often a vibrant prop on stage—amplifies the absurdity, as characters like Titania fall for unintended partners like Bottom.

Another standout is Bottom’s donkey head, a prop that epitomizes physical comedy. When Puck transforms Bottom, the head becomes a visual gag, its absurdity heightened by Bottom’s obliviousness. Directors often exaggerate this prop’s size or texture to maximize laughs, as seen in Julie Taymor’s 2014 film adaptation, where the head’s grotesque features stole the show. These props not only entertain but also underscore themes of transformation and illusion, central to Shakespeare’s comedic vision. For modern directors, emphasizing a prop’s visual flair—through color, movement, or staging—can heighten its comedic impact.

Props as Symbols of Power in Histories

In Shakespeare’s history plays, props often symbolize power, legitimacy, or conflict, grounding political dramas in tangible objects. The crown in Richard III is a prime example, embodying the contested throne. When Richard manipulates his way to power, the crown’s physical presence—whether worn or offered—signals his ambition and eventual downfall. Scholar Marjorie Garber notes that the crown “carries the weight of history itself,” reflecting the fragility of authority in Shakespeare’s histories (Garber, Shakespeare After All). On stage, its gleam or tarnish can visually cue the audience to shifts in power.

Similarly, in Henry V, the sword serves as a prop of martial prowess and leadership. Henry’s rallying cries, like “Once more unto the breach,” are often accompanied by a raised sword, symbolizing resolve. In Kenneth Branagh’s 1989 film, the sword’s prominence during battle scenes reinforced Henry’s heroic image. These props anchor the histories’ grand narratives in physical reality, making abstract struggles for power vivid and relatable. Directors can enhance this effect by staging props prominently—perhaps placing a crown center-stage during a coronation or having a sword catch the light during a speech.

Practical Applications for Modern Theater and Education

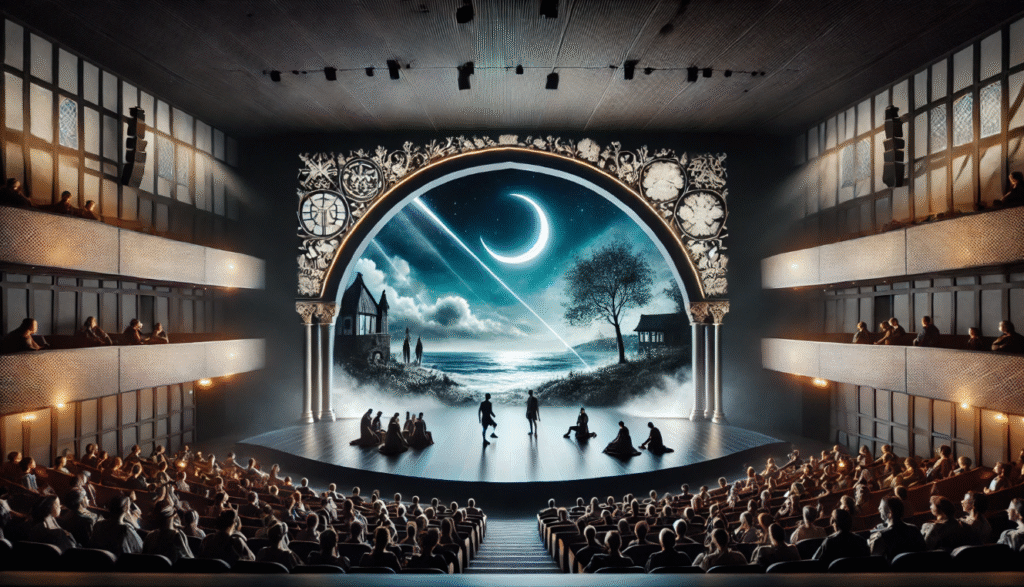

Using Props in Contemporary Productions

The use of props to enhance dramatic effect in Shakespeare’s plays remains vital in modern theater, where directors adapt these objects to resonate with today’s audiences. Minimalist productions might use a single, striking prop—like a bloodied cloth in Macbeth—to evoke an entire scene’s mood. In contrast, elaborate stagings, such as the 2016 Globe production of The Tempest, incorporate digital projections as “props,” with Ariel’s magical effects rendered as glowing orbs. These modern adaptations show how props can bridge Shakespeare’s era and ours, maintaining their dramatic power.

Directors can maximize impact by choosing props that resonate visually and thematically. For instance, in Othello, a handkerchief might be embroidered with culturally significant patterns to reflect Desdemona’s heritage, adding depth to the production. Practical tip: Ensure props are handled dynamically—actors should interact with them purposefully, as in Hamlet’s tactile engagement with Yorick’s skull, to convey emotion. Consulting historical texts, like Philip Henslowe’s diaries, can also guide authentic prop choices, reinforcing a production’s credibility.

Teaching Shakespeare with Props

Educators can harness props to make Shakespeare accessible and engaging for students. By bringing objects like a mock crown, a letter, or a toy sword into the classroom, teachers can transform abstract texts into tangible experiences. For example, reenacting the handkerchief scene from Othello allows students to discuss its symbolism while physically handling the prop, fostering deeper understanding. A lesson plan might involve students staging a short scene from Macbeth, using a prop dagger to explore its psychological weight. This hands-on approach, endorsed by educators like those at the Folger Shakespeare Library, helps students connect with themes like ambition or betrayal.

Resource Idea: Create a prop-based activity where students select a prop from a play (e.g., a ring from The Merchant of Venice) and analyze its role in a group discussion. Provide a worksheet with prompts: “How does this prop advance the plot?” or “What emotions does it evoke?” This exercise builds critical thinking and engagement, addressing the need for interactive learning.

The Lasting Impact of Shakespeare’s Props

Why Props Remain Relevant Today

The use of props to enhance dramatic effect in Shakespeare’s plays transcends time, influencing modern theater, film, and even literature. Props like the skull in Hamlet find echoes in contemporary storytelling, such as the orange in The Godfather, a subtle omen of death. Their ability to convey universal themes—mortality, power, love—ensures their relevance. In film, directors like Baz Luhrmann (in his 1996 Romeo + Juliet) use modern props, like guns instead of swords, to preserve Shakespeare’s dramatic intent while updating the setting. This adaptability shows how props remain a cornerstone of visual storytelling.

Theater practitioners continue to draw on Shakespeare’s techniques. Director Emma Rice, in her 2016 A Midsummer Night’s Dream, used oversized, whimsical props to amplify comedy, proving their versatility. By studying Shakespeare’s props, modern creators learn to craft objects that resonate emotionally and narratively, ensuring audiences remain captivated.

Connecting Audiences Across Time

Props bridge Elizabethan and modern audiences through shared human experiences. A dagger, a crown, or a letter speaks to universal emotions—fear, ambition, trust—that transcend centuries. When a modern audience sees Hamlet hold Yorick’s skull, they feel the same existential weight as Elizabethan viewers, thanks to the prop’s enduring power. This connection is why Shakespeare’s plays remain performed worldwide, from London’s Globe to community theaters.

Theater scholar Tiffany Stern argues that props “collapse time,” linking past and present through their physicality (Stern, Making Shakespeare). A modern production of King Lear might use a weathered crown to evoke Lear’s decline, resonating with audiences grappling with themes of loss. By engaging with props, audiences connect with Shakespeare’s world, making his stories as vital today as they were 400 years ago.

From the haunting dagger in Macbeth to the transformative flower in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the use of props to enhance dramatic effect in Shakespeare’s plays creates unforgettable scenes that linger in the mind. These objects—laden with symbolism, plot significance, and character insight—transformed the sparse Elizabethan stage into a vivid world of emotion and action. Their legacy endures in modern theater and education, offering directors tools to captivate audiences and teachers ways to engage students. To experience this magic firsthand, attend a local Shakespeare production or try a prop-based classroom activity. Explore related articles on our blog, like “Symbolism in Shakespeare’s Tragedies” or “Staging Shakespeare Today,” to deepen your appreciation of his craft.

FAQs

What are some famous props in Shakespeare’s plays?

Iconic props include the dagger in Macbeth (symbolizing guilt), the handkerchief in Othello (representing trust), and Yorick’s skull in Hamlet (evoking mortality). Each drives the narrative and deepens themes.

How did Elizabethan audiences interpret props differently than modern audiences?

Elizabethan audiences, steeped in symbolic traditions, read props like crowns or letters as layered metaphors. Modern audiences, accustomed to visual media, may focus on props’ emotional or visual impact, though directors can bridge this gap with thoughtful staging.

Can props be used effectively in minimalist Shakespeare productions?

Yes, minimalist productions thrive on props’ versatility. A single prop, like a bloodied cloth in Macbeth, can evoke entire settings or emotions, as seen in the 2015 Globe production of Othello.

How can teachers use props to make Shakespeare engaging for students?

Teachers can use props like a mock crown or letter in classroom activities, such as reenacting scenes or analyzing symbolism. These hands-on exercises, recommended by the Folger Shakespeare Library, foster engagement and critical thinking.