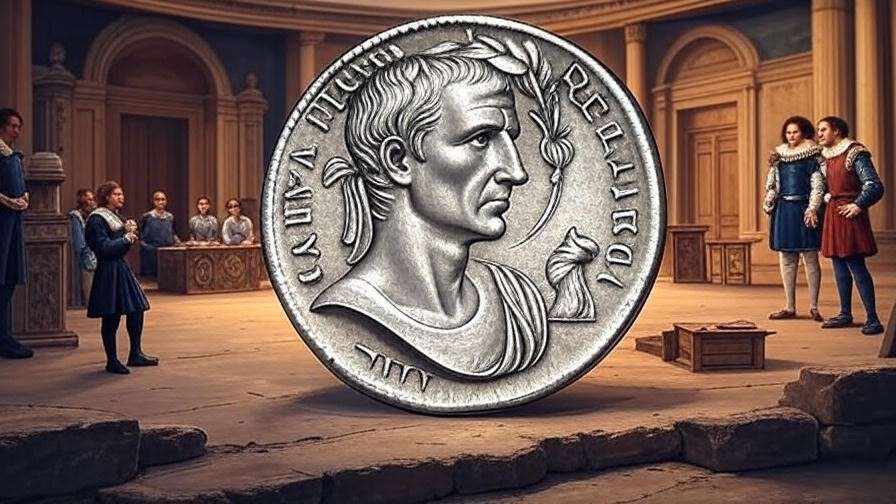

Imagine holding in your hand a small silver disc struck over two millennia ago—one that circulated in the streets of Rome just weeks before Julius Caesar’s assassination on the Ides of March in 44 BC. Etched on its surface is the first living portrait of a Roman ever to appear on coinage: Caesar himself, wreathed in laurel, titled “DICT PERPETVO” (Dictator for Life). These coins of Julius Caesar were not mere money; they were bold instruments of propaganda, broadcasting his unprecedented power, divine ancestry, and military dominance to every citizen who handled them. They fueled resentment among the elite, accelerated the fall of the Roman Republic, and left an indelible mark on history—one that William Shakespeare would later immortalize in his tragedy Julius Caesar.

For readers drawn to ancient Roman history, numismatics, or Shakespeare’s Roman plays, these artifacts offer a tangible bridge between real events and dramatic literature. They reveal how Caesar used currency as mass media to project ambition that mirrored the hubris Shakespeare dramatizes, while also providing clues to why his enemies felt compelled to act. This in-depth guide explores the major types of Caesar’s coins, their symbolism, historical context, collecting considerations, and direct ties to Shakespeare’s masterpiece—delivering deeper insights than standard overviews and helping enthusiasts, students, and collectors understand these revolutionary pieces fully.

The Historical Context: Why Julius Caesar Minted His Own Coins

From Republic to Personal Power – The Breakdown of Traditional Norms

Roman coinage before Caesar strictly adhered to tradition: obverses featured gods, Roma (the personification of Rome), or legendary ancestors; living individuals never appeared. This reflected the Republic’s aversion to monarchy and personal cults, a safeguard against tyranny after the expulsion of the kings in 509 BC.

By the late 50s BC, however, civil strife eroded these norms. Caesar’s conquest of Gaul (58–50 BC) brought immense wealth and a loyal veteran army. When the Senate ordered him to disband his legions and return to Rome as a private citizen, he crossed the Rubicon in 49 BC, igniting civil war against Pompey and the optimates. To fund his campaigns—paying legions, bribing allies, and sustaining supply lines—Caesar seized control of Rome’s mints and treasury. He began issuing coins in his name from military mints traveling with his army, marking a shift toward personalized propaganda.

Caesar as Innovator – The First Living Portrait on Roman Coinage

The most revolutionary change came in early 44 BC. After his triumphs, the Senate bestowed honors including perpetual dictatorship. Caesar’s coins began featuring his own portrait—laureate, sometimes veiled—breaking the taboo decisively. This innovation, inspired perhaps by Hellenistic ruler portraits (Alexander the Great, Ptolemaic kings), signaled Caesar’s quasi-divine status and monarchical ambitions. Ancient sources like Suetonius and Cassius Dio note how these coins alarmed traditionalists, who saw them as evidence of kingship—the very charge that justified the conspiracy.

In an era without newspapers or social media, coins reached millions. Denarii (silver, worth about a day’s wage) circulated widely, carrying Caesar’s image and titles into markets, legions, and provinces. They functioned as enduring political messaging, reinforcing loyalty among supporters and intimidating opponents.

The Most Iconic Coins of Julius Caesar – A Chronological Guide

Caesar’s coinage, cataloged in Michael Crawford’s seminal Roman Republican Coinage (RRC), evolves from military victory symbols to overt self-promotion. Key issues include:

The Famous “Elephant” Denarius (c. 49–48 BC)

One of the most recognizable and accessible of Caesar’s lifetime issues (RRC 443/1), this denarius features an elephant advancing right, trampling a horned serpent (often interpreted as a carnyx, the Gallic war trumpet, or a symbol of enemies like Pompey). Below, “CAESAR” in exergue. The reverse displays pontifical emblems: simpulum (ladle), aspergillum (sprinkler), securis (axe), and apex (priest’s cap)—symbols of Caesar’s role as Pontifex Maximus.

Symbolism remains debated among numismatists. Some see the elephant as Caesar overwhelming foes (trampling Pompey or Gaul); others link it to a family legend of an ancestor killing an elephant single-handedly, or to Alexander the Great’s Indian campaigns (elephants symbolizing invincible power). Struck in massive quantities to pay troops during the civil war, this type is the most common surviving Caesar coin, with estimates suggesting millions produced.

Venus and Aeneas Types (c. 47–46 BC)

Following victories in Egypt and Africa (RRC 458/1, etc.), these celebrate Caesar’s claimed descent from Venus (via Aeneas, Trojan hero and Rome’s mythical founder). Obverse: diademed head of Venus right. Reverse: Aeneas carrying Anchises from burning Troy, Palladium in hand. These reinforce divine ancestry, legitimacy, and conquests, portraying Caesar as Rome’s destined savior.

Lifetime Portrait Denarii (Early 44 BC) – The “Coin That Killed Caesar”

The pinnacle of Caesar’s numismatic innovation: portrait issues struck January–March 44 BC (RRC 480 series). Obverse: wreathed/veiled head of Caesar right, legends like “CAESAR DICT PERPETVO.” Reverses vary—Venus Victrix holding Victory and scepter (moneyers like P. Sepullius Macer, L. Aemilius Buca), or seated Victory. These proclaimed perpetual dictatorship, alarming senators who feared monarchy. Historians link their circulation to growing conspiracy fervor; some call them “the coins that killed Caesar” for embodying the hubris that provoked the Ides plot.

Posthumous and Related Issues

After assassination, Octavian (future Augustus) issued commemoratives deifying Caesar (“DIVVS IVLIVS”). Brutus, a conspirator, struck the ironic “Eid Mar” denarius (RRC 508/3): cap of liberty between daggers, “EID MAR” below—celebrating “liberation” on the Ides. These underscore the coins’ role in propaganda wars post-Caesar.

Symbolism and Propaganda – Decoding the Messages on Caesar’s Coins

Caesar’s coin designs were far from decorative; they constituted sophisticated political messaging in an age when visual propaganda reached every corner of the empire. By layering symbols of military triumph, divine lineage, religious authority, and personal power, these pieces reinforced Caesar’s narrative as Rome’s indispensable leader.

Military Triumph and Divine Ancestry

The elephant denarius stands as a prime example of triumph symbolism. The massive elephant trampling a serpent-like creature (variously interpreted as a carnyx—a Gallic war trumpet—a dragon, or a snake representing evil or Pompeian foes) evokes overwhelming victory. Numismatic scholars debate the exact meaning: some link it to Caesar’s Gallic Wars, where elephants symbolized unstoppable force (echoing Hannibal or Alexander); others see it as personal propaganda against Pompey, portraying Caesar as the elephant crushing the serpentine opposition. A family legend of an ancestor slaying an elephant single-handedly has also been proposed, tying into Roman ancestral pride.

Venus and Aeneas types deepen the divine claim. Venus, as ancestress of the Julian gens through Aeneas (who fled Troy carrying his father Anchises and the Palladium), positioned Caesar as heir to Rome’s mythical founders. These coins, issued after African and Egyptian campaigns, subtly connected victories to destiny and piety—Venus Victrix (conquering) on some reverses underscored military success under divine favor.

Religious Authority and Priesthood

Pontifical symbols recur across issues: the simpulum (ritual ladle), aspergillum (sprinkler), securis (axe, often with wolf’s head), and apex (flamen’s cap). As Pontifex Maximus since 63 BC, Caesar emphasized his supreme religious role, lending spiritual legitimacy to his political dominance. In a Republic wary of kings, these emblems framed autocracy as sacred duty.

Political Arrogance vs. Genius

The lifetime portrait denarii represent the boldest propaganda. Featuring Caesar’s head—often veiled as Pontifex or laureate as triumphator—with titles like “DICT PERPETVO,” they asserted perpetual rule. Ancient critics viewed this as monarchical arrogance; modern historians see genius in using coinage as ubiquitous media to normalize his authority amid civil war chaos. The portraits broke Republican tradition decisively, paving the way for imperial iconography under Augustus.

These symbols collectively transformed currency into a tool for shaping public perception, blending personal ambition with Roman values.

Coins of Julius Caesar in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar – Bridging History and Drama

Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar (c. 1599) draws heavily from Plutarch, Suetonius, and Appian, but the coins provide a material echo of the ambition and hubris he dramatizes. They offer modern readers a visual lens into the historical Caesar whose actions inspired the tragedy.

Echoes of Ambition and Hubris

Caesar’s “constant as the northern star” speech (Act 3, Scene 1) proclaims unyielding authority, mirroring the lifetime coins’ “DICT PERPETVO” assertion. The play’s Caesar refuses the crown thrice yet accepts divine honors—paralleling how his portrait coins projected god-like status, alarming conspirators. Shakespeare amplifies the hubris that coins visually broadcast: Caesar’s self-deification on silver denarii fueled real resentment, just as dramatic arrogance leads to betrayal.

The Ides of March and Assassination

The soothsayer’s warning—”Beware the Ides of March”—gains poignancy against the backdrop of Caesar’s circulating portraits in early 44 BC. These coins, proclaiming perpetual dictatorship, intensified Senate fears of tyranny. Shakespeare’s assassination scene captures the conspiracy’s fervor; the coins symbolize the tipping point where propaganda became provocation.

Brutus’s “Eid Mar” denarius—struck post-assassination with daggers flanking a liberty cap and “EID MAR”—ironically celebrates the “liberation” Shakespeare dramatizes in Brutus’s conflicted soliloquies. While not Caesar’s issue, it ties directly to the play’s themes of republicanism vs. autocracy.

Currency References in the Play

Shakespeare includes monetary allusions: Antony’s funeral oration mentions Caesar leaving “seventy-five drachmas” to each citizen (Act 3, Scene 2). In Elizabethan England, audiences understood Roman coinage through contemporary parallels; drachmas evoked everyday value, heightening the tragedy’s stakes. These nods ground the drama in historical economic reality, where Caesar’s coins funded loyalty and power.

By connecting numismatic evidence to Shakespeare’s text, readers gain richer insight into how real artifacts amplified the themes of ambition, betrayal, and republican fragility.

Collecting Coins of Julius Caesar – What Enthusiasts Need to Know

For collectors, historians, or Shakespeare fans seeking tangible links to antiquity, Caesar’s coins offer rewarding pursuit—though authenticity and condition matter greatly.

Rarity, Values, and Market Trends

The elephant denarius (RRC 443/1) remains the most accessible lifetime issue. In recent auctions and dealer listings (2024–2026 data), well-preserved examples grade VF to XF fetch $1,000–$3,000+, with exceptional NGC-certified pieces reaching $2,000–$5,000 or more. Lifetime portrait denarii are rarer and pricier: VF examples often sell for $3,000–$10,000+, with high-grade or rare varieties exceeding $8,000–$20,000+.

Values fluctuate with market conditions, but demand stays strong due to historical fame. Posthumous and related issues (e.g., Octavian’s Divus Julius) vary widely.

Where to Find Authentic Examples

Purchase from reputable sources: NGC or ANACS certified dealers, major auction houses (e.g., CNG, Heritage, Nomos), or established platforms like VCoins. Avoid unverified eBay or private sales without provenance. Museums (British Museum, American Numismatic Society) display originals for study.

Modern Replicas and Educational Value

High-quality replicas (silver or gold-plated) cost $20–$100 and suit educational/display purposes—ideal for Shakespeare enthusiasts visualizing the play’s context without investing thousands. Always distinguish replicas from authentic ancients.

Collecting these coins connects directly to history and literature, offering a personal encounter with the propaganda that shaped empires and inspired tragedy.

Expert Insights and Lesser-Known Facts

- An estimated 22–30 million elephant denarii were minted—yet high-grade survivors are prized due to circulation wear.

- Caesar’s lifetime portraits initiated the Roman imperial tradition of ruler iconography, influencing Augustus and beyond.

- Symbolism debates persist: the elephant-serpent motif may mock Pompey (snake as his “Asiatic” foes) or appropriate Metelli family badges.

- The “Eid Mar” denarius ranks among the most famous ancients, symbolizing tyrannicide—its scarcity (fewer than 100 known) underscores post-assassination propaganda intensity.

- Shakespeare’s audience, familiar with classical texts, would recognize coin allusions as reinforcing Caesar’s historical overreach.

The coins of Julius Caesar stand as revolutionary artifacts: small silver pieces that accelerated the Republic’s end while proclaiming one man’s rise to near-divine power. From the elephant’s trampling might to the lifetime portrait’s bold declaration, they served as propaganda masterpieces that provoked the Ides conspiracy and echoed through centuries.

For Shakespeare lovers, these coins illuminate the ambition and hubris at the heart of Julius Caesar—Caesar’s real self-promotion mirroring the tragic figure who refuses omens and crowns. They remind us how visual symbols can sway empires and inspire art.

Explore further: visit museum collections, read Plutarch’s Life of Caesar or Suetonius, or revisit Shakespeare’s play with numismatic context in mind. These enduring pieces continue to speak of power’s allure and republics’ fragility.

FAQs

What is the most famous coin of Julius Caesar? The elephant denarius (49–48 BC) is the most iconic and accessible, celebrated for its bold symbolism and massive mintage.

How do Caesar’s coins relate to Shakespeare’s play? They visually embody the ambition and dictatorship that Shakespeare dramatizes, with lifetime portraits echoing Caesar’s hubris and the Ides events fueling the tragedy.

Are Julius Caesar coins valuable today? Yes—elephant types start around $500–$1,000 in lower grades, while rare lifetime portraits can exceed $10,000+ in high condition, depending on certification and market.

Why did Caesar put his portrait on coins? To assert unprecedented authority, claim divine ancestry, and use currency as propaganda during civil war—breaking Republican tradition.

What does the elephant on Caesar’s coin symbolize? Theories include Gallic victories, overwhelming enemies (trampling a serpent/snake/dragon), family legend, or mocking rivals like Pompey.

Where can I see authentic examples? Major institutions like the British Museum, Louvre, or online via NGC Ancients and CoinArchives.