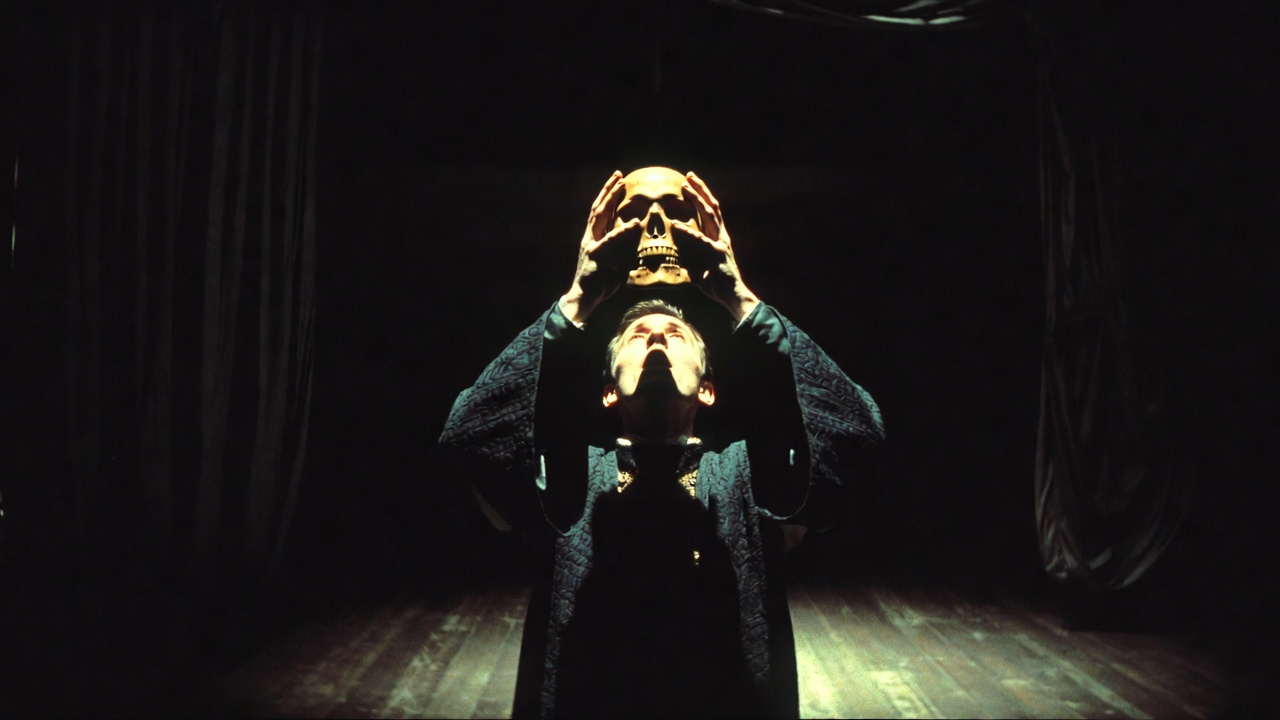

Imagine standing in a silent graveyard at dusk, the only sound the scrape of a shovel against earth, when a young prince lifts a human skull from the dirt and speaks to it as if greeting an old friend: “Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him, Horatio…” For more than four hundred years, this single image—Hamlet with skull in hand—has become one of the most instantly recognizable symbols in world literature, theater, and visual art. It captures, in one frozen gesture, the entire weight of human existence: joy turned to dust, power reduced to bone, laughter silenced forever.

Why does this moment continue to haunt and fascinate us? Why has a thirty-something Danish prince holding a jester’s skull become shorthand for philosophy, mortality, and Shakespeare himself?

In Act 5, Scene 1 of Hamlet, the so-called graveyard scene (or gravediggers’ scene) marks the philosophical and emotional climax of the tragedy. After years of hesitation, feigned madness, exile, and grief, Hamlet returns to Elsinore and stumbles upon Yorick’s skull during preparations for Ophelia’s burial. What begins as dark comedy among the gravediggers quickly deepens into one of the most powerful meditations on death, equality, the vanity of life, and the acceptance of fate ever written in English.

This article offers the most comprehensive, text-grounded exploration of the “Hamlet with skull” scene available anywhere—drawing directly from Shakespeare’s language, Elizabethan context, performance history, scholarly interpretations, and its striking relevance today. Whether you are a literature student preparing for an exam, a theatergoer wanting deeper insight before seeing a production, or simply someone who has always wondered what that famous skull really means, you will leave this page with a clearer, richer understanding of why this moment stands at the very heart of Shakespeare’s masterpiece.

The Context of the Graveyard Scene in Hamlet

Where and When It Occurs in the Play

The graveyard scene opens Act 5, Scene 1—the second-to-last scene of the tragedy. By this point the plot has reached critical mass: Hamlet has accidentally killed Polonius, been sent to England under a secret death warrant (which he cleverly evades), learned of Ophelia’s drowning, and returned to Denmark just in time for her funeral. The graveyard therefore serves as both literal and symbolic threshold: the place where the living confront the dead before the final bloodbath of the duel and multiple deaths in the closing scene.

Structurally, it is the hinge between Hamlet’s long period of intellectual paralysis and his sudden, almost serene readiness to act. The shift is subtle but decisive.

Key Characters Present

- The two gravediggers (clowns): Professional sextons digging Ophelia’s grave. Their earthy, pun-laden dialogue provides comic relief and simultaneously voices some of the play’s darkest truths about suicide, class, and the law.

- Hamlet and Horatio: They watch from a distance at first, then Hamlet engages directly with the First Gravedigger.

- The absent but ever-present figures: Ophelia (whose grave is being prepared), Yorick (whose skull is unearthed), and the long-dead Alexander the Great and Caesar (invoked in Hamlet’s imagination).

The gravediggers’ casual irreverence contrasts sharply with Hamlet’s intense philosophical response, creating one of Shakespeare’s most effective juxtapositions of low comedy and high tragedy.

Immediate Build-Up and Dramatic Irony

Hamlet and Horatio arrive just as the First Gravedigger is debating whether Ophelia deserves a Christian burial (since her death appears self-inflicted). Their crude legalistic banter—“Is she to be buried in Christian burial when she wilfully seeks her own salvation?”—is both funny and chilling. The audience knows far more than the gravediggers: we understand the chain of violence and despair that led to Ophelia’s death. This dramatic irony primes us for the skull’s appearance: an anonymous bone suddenly becomes deeply personal.

The Famous “Alas, Poor Yorick!” Monologue – Full Breakdown and Text

Here is the heart of the scene (modernized spelling for clarity, but preserving Shakespeare’s wording; line numbers approximate from the Folio):

Hamlet Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him, Horatio—a fellow of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy. He hath bore me on his back a thousand times, and now how abhorred in my imagination it is! My gorge rises at it. Here hung those lips that I have kissed I know not how oft.—Where be your gibes now? your gambols? your songs? your flashes of merriment that were wont to set the table on a roar? Not one now to mock your own grinning? Quite chapfallen?

Now get you to my lady’s chamber and tell her, let her paint an inch thick, to this favor she must come. Make her laugh at that.—Prithee, Horatio, tell me one thing. Horatio What’s that, my lord? Hamlet Dost thou think Alexander looked o’ this fashion i’ th’ earth? Horatio E’en so. Hamlet And smelt so? Pah! [He sets the skull down] To what base uses we may return, Horatio! Why may not imagination trace the noble dust of Alexander till he find it stopping a bunghole?

Line-by-line insight

- “Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him, Horatio” — The sudden shift from general observation to intimate recognition is devastating. Yorick was not just any skull; he was the court jester who once carried young Hamlet on his back, a surrogate father-figure of joy.

- The physical revulsion (“My gorge rises at it”) contrasts with remembered affection, showing how death transforms love into nausea.

- The rapid-fire questions—“Where be your gibes now? your gambols? your songs?”—are rhetorical cries of loss. The vitality that once filled a room is now reduced to grinning bone.

- The command to the imaginary lady (“let her paint an inch thick, to this favor she must come”) is a brutal reminder of cosmetic vanity. Beauty, like merriment, ends the same way.

- The leap to Alexander the Great and the bunghole image is grotesque and brilliant: even the conqueror of the world becomes mere stopper in a barrel. It universalizes the personal grief.

Deep Symbolism of the Skull in “Hamlet with Skull”

The skull is far more than a morbid prop; it functions as one of the richest, multi-layered symbols in all of Shakespeare. Scholars and directors have returned to it for centuries because it condenses several interlocking ideas into a single, silent object.

Memento Mori – “Remember You Must Die”

The phrase memento mori (“remember that you must die”) originates in medieval Christian tradition, where a skull or death’s-head reminded the living of life’s brevity and the need for spiritual preparation. In Renaissance England, this motif appeared everywhere: on tombstones, in paintings, in jewelry. Shakespeare takes this convention and dramatizes it. When Hamlet holds Yorick’s skull, he literally confronts the physical reality of death—not an abstract idea, but a grinning, eyeless face that once laughed and spoke. The skull forces both Hamlet and the audience into an immediate, visceral encounter with mortality.

Equality and the Leveling Power of Death

One of the most radical statements in the monologue is the erasure of social hierarchy in death. Hamlet moves swiftly from Yorick the jester to Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar:

“Alexander died, Alexander was buried, Alexander returneth to dust, the dust is earth… Why may not imagination trace the noble dust of Alexander till he find it stopping a bunghole?”

In life, Alexander conquered empires; in death, his dust might plug a beer barrel. Likewise, the gravediggers earlier remark that “your tanner will last you nine year” because his hide is tanned into leather—another leveling of class distinctions. Death democratizes: king, clown, courtier, and commoner all become identical bone. This was a subversive idea in a rigidly hierarchical Elizabethan society, and it remains powerfully egalitarian today.

Existential Nihilism and the Meaninglessness of Life

Hamlet’s tone is not merely mournful—it borders on nihilistic. The reduction of “infinite jest” and “most excellent fancy” to a stinking skull suggests that human achievements, wit, beauty, and ambition are ultimately futile. This connects directly to the earlier “To be, or not to be” soliloquy, where Hamlet contemplates whether existence itself is worth enduring. The graveyard scene answers that question with brutal clarity: everything ends in dust. Yet, unlike the earlier speech, there is no despairing paralysis here—only a grim acceptance that clears the way for action.

Personal Loss and Nostalgia for Innocence

On the most intimate level, Yorick represents Hamlet’s lost childhood. The jester who carried the boy prince “on his back a thousand times” embodies a time before betrayal, murder, and melancholy overwhelmed Hamlet’s world. Holding the skull is therefore an act of mourning not only for Yorick, but for the innocence and joy that Hamlet can never recover. This personal dimension makes the universal symbolism feel achingly human.

How the Skull Scene Represents a Turning Point for Hamlet’s Character

Before Act 5, Hamlet is defined by hesitation, over-analysis, and performative madness. He knows what he must do (avenge his father), yet he cannot act. The graveyard scene changes that trajectory.

- Before the skull: Hamlet is trapped in intellectual loops, questioning everything, delaying revenge.

- During the monologue: He confronts death directly and emerges changed. The grotesque humor of the Alexander/bunghole image is almost liberating—it strips away illusions of grandeur and leaves only the present moment.

- After the scene: When challenged by Laertes at Ophelia’s grave, Hamlet declares, “I loved Ophelia. Forty thousand brothers / Could not with all their quantity of love / Make up my sum.” Later, he tells Horatio, “If it be now, ’tis not to come… the readiness is all.” The paralysis is gone; fatalistic resolve takes its place.

Many scholars (including A.C. Bradley and Harold Bloom) view this as the moment Hamlet sheds his neurotic overthinking and achieves tragic clarity. The skull does not give him answers—it removes the need for them. Death is certain; therefore, the only meaningful choice is how one meets it.

Theatrical and Performance History of the “Hamlet with Skull” Moment

The “Hamlet with skull” pose has become the single most iconic visual associated with Shakespeare. Its performance history reveals how directors and actors have interpreted its weight.

- Early productions used real human skulls; the practice continued into the 20th century. In 1982, the Royal Shakespeare Company used the skull of André Tchaikowsky (a Polish composer who bequeathed his skull to the RSC for use in Hamlet).

- Famous interpretations include:

- David Garrick (18th century): emphasized sentimental pathos.

- John Gielgud (1930s–40s): introspective melancholy.

- David Tennant (2008 RSC): raw, modern anguish.

- Jude Law (2009): athletic intensity paired with philosophical depth.

- Directors have experimented wildly: setting the scene in rain, snow, or stark white light; using a plastic skull, a realistic prop, or even no skull at all (relying on mime).

The image has transcended theater: it appears in paintings (Delacroix, Millais), films (Olivier’s 1948 version, Branagh’s 1996 epic), cartoons, tattoos, album covers, and countless memes. It is the visual synecdoche for “Shakespeare” itself.

Broader Themes Reinforced by the Graveyard Scene

The scene crystallizes several of the play’s central motifs:

- Revenge vs. acceptance of fate

- Appearance vs. reality (the skull reveals the truth beneath cosmetic facades)

- Corruption of the court vs. the honesty of death

- The interplay of comedy and tragedy (gravediggers’ puns vs. Hamlet’s profundity)

It also raises theological questions: Is there an afterlife? Does Christian burial matter when all end the same? Shakespeare leaves these ambiguities open, allowing audiences to project their own beliefs.

Modern Relevance and Why “Hamlet with Skull” Still Resonates Today

In an era of pandemics, climate anxiety, and lengthening lifespans shadowed by mortality awareness, the graveyard scene speaks with renewed urgency. It asks: Knowing death is inevitable, how should we live? The answer is not despair, but mindfulness—living fully in the present while accepting impermanence.

Yorick’s skull appears in popular culture as a shorthand for existential reflection: in The Lion King (“Everything the light touches…”), in philosophical memes, in art therapy exercises about grief. It reminds us that humor, love, and creativity exist precisely because time is finite. As Hamlet says earlier, “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, / Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” The skull scene proves it.

FAQs About the Hamlet Skull Scene

What does the skull represent in Hamlet? Primarily mortality, the leveling power of death, vanity of earthly pursuits, and personal loss—while serving as a catalyst for Hamlet’s final acceptance of fate.

Whose skull is it, and why Yorick specifically? It belongs to Yorick, the king’s jester from Hamlet’s childhood. Shakespeare chose a specific, beloved figure to make the confrontation emotionally devastating rather than abstract.

Is “Alas, poor Yorick” the exact quote? Yes—“Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him, Horatio…” is verbatim from the First Folio and modern editions.

Why is this scene so famous in theater history? It combines profound philosophy, dark humor, intimate character revelation, and a striking visual image that has been endlessly reproduced.

Has a real human skull ever been used in performances? Yes—most famously André Tchaikowsky’s skull at the RSC from 1982 onward (with permission and after ethical review).

The “Hamlet with skull” moment is not merely dramatic flair; it is the philosophical fulcrum of Shakespeare’s greatest tragedy. In thirty lines of dialogue, Shakespeare compresses the human condition: our capacity for joy, our fear of oblivion, our illusions of permanence, and our ultimate equality before death. Holding Yorick’s skull, Hamlet holds a mirror up to every viewer—reminding us that, for all our striving, we too will one day be dust.

Yet the scene is not hopeless. By accepting mortality, Hamlet finds the clarity to act, to love, to face the end with courage. That is the deepest gift of the graveyard: not despair, but the fierce, fragile beauty of being alive while we still can.

So the next time you see that famous image—whether in a theater, a textbook, or a meme—remember: it is not just Hamlet with a skull. It is every one of us, invited to laugh, grieve, reflect, and live more fully before the curtain falls.