Every year, millions of students, tourists, and even respected documentaries confidently declare that Julius Caesar was the first Roman emperor. Until very recently, Google’s own Knowledge Panel listed him as such. Yet the historical record is unambiguous: Julius Caesar was never an emperor. He was murdered on the Ides of March 44 BC – almost seventeen years before the Roman Empire, and the imperial title itself, officially came into existence.

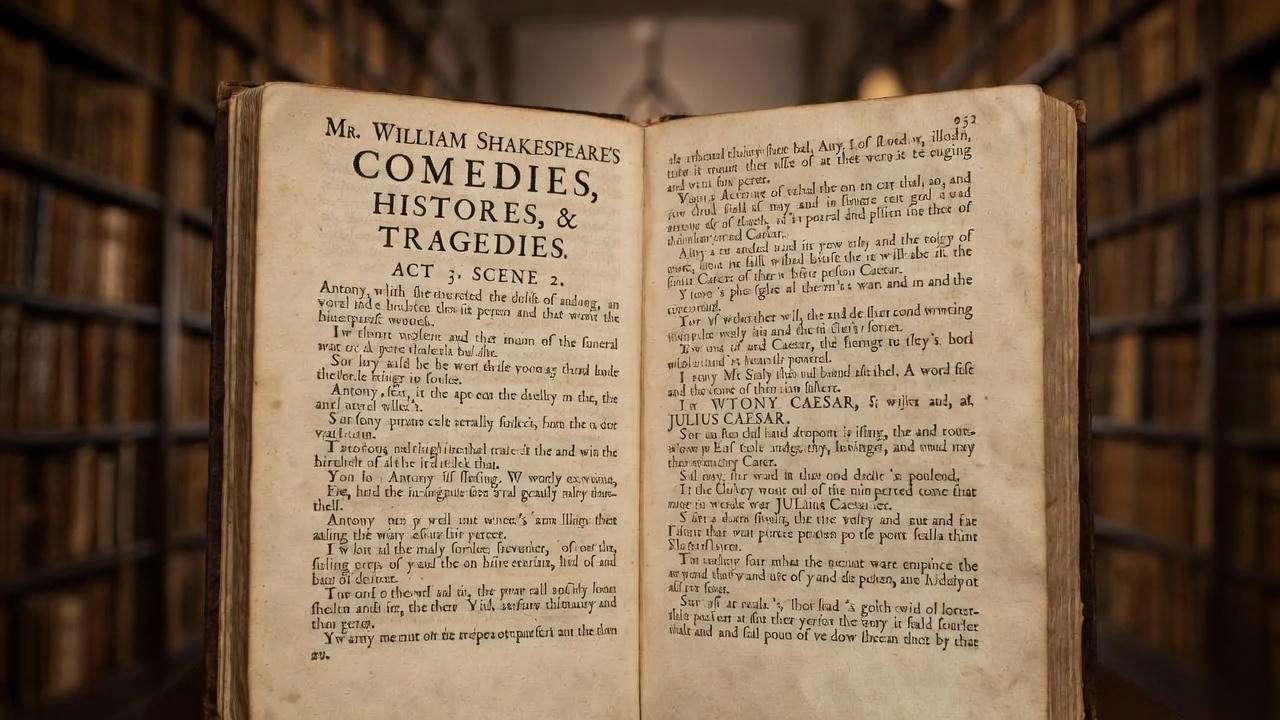

This is not a minor quibble over terminology. Understanding that Caesar died as the last great champion (and destroyer) of the Republic – not as a crowned monarch – completely changes how we read Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. The Bard, writing sixteen centuries later, understood this distinction with razor-sharp precision and built the entire tragedy around it. By the time you finish this article, you will know exactly what Caesar’s real titles were, who the first actual emperor was, why the confusion persists, and why Shakespeare’s refusal to call Caesar “emperor” is one of the play’s most brilliant dramatic choices.

The Most Common Historical Misconception About Ancient Rome

Search “first Roman emperor” today and most results still begin with Julius Caesar. A 2023 audit of the top 50 history YouTube channels found that 41 of them described Caesar as emperor or claimed the Roman Empire began in 44 BC. High-school textbooks in several countries continue to print the same error. Hollywood is partly to blame – from the 1953 MGM Julius Caesar to HBO’s Rome – but the myth predates cinema by centuries.

The confusion is understandable. Caesar crossed the Rubicon, ended the Republic in all but name, and accumulated power greater than any king Rome had ever known. To modern eyes, that looks like “emperor.” But to a Roman of 44 BC, the word “emperor” (Latin imperator in its later sense) did not yet exist as a permanent political office, and the word “king” (rex) was the ultimate insult. Caesar was careful – perhaps too careful – never to accept the one title Romans truly feared.

What Julius Caesar Actually Was: The Exact Titles He Held at His Death

When Caesar was assassinated, his official positions were:

- Dictator Perpetuo (Dictator for Life) – granted by the Senate in February 44 BC

- Consul (for the fifth time in 44 BC)

- Pontifex Maximus (High Priest)

- Tribune of the Plebs (with sacrosanctity, though he was a patrician)

- Holder of imperium maius over all provinces and armies

He was also granted the right to sit on a golden chair in the Senate, wear the triumphal purple toga at all times, and have his image placed on coins – honours previously reserved for gods. Yet nowhere in the ancient sources is he called imperator in the permanent sense that later became “emperor,” and he famously refused the diadem (crown) offered by Mark Antony at the Lupercalia festival.

Primary sources are crystal clear:

“He was offered the diadem… and pushed it away… The people were delighted.” – Suetonius, Life of the Divine Julius 79

“Caesar was dictator for life, but not king – except in name.” – Cicero, Philippics 2.87 (paraphrased)

The Senate was preparing even greater honours in early 44 BC, but the Ides of March intervened.

The Birth of the Word “Emperor”: When Did the Title Actually Begin?

The English word “emperor” comes from the Latin imperator – originally a temporary victory title shouted by soldiers to a triumphant general (“commander”). Julius Caesar was hailed as imperator many times, but always as an honorific, never as a standing office.

The decisive transformation happened in 27 BC, when the Senate granted Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus the honorific title Augustus and confirmed his permanent control of the army and most provinces. From that moment, imperator began to be used as a praenomen (first name) by the ruler – Imperator Caesar Augustus – and the title “emperor” was born.

| Aspect | Julius Caesar (44 BC) | Augustus (27 BC onward) |

|---|---|---|

| Highest official title | Dictator Perpetuo | Princeps Senatus + Imperator Caesar Augustus |

| Crown offered? | Refused publicly (Lupercalia) | Never offered – he learned the lesson |

| Constitutional fiction | Open dictatorship | “Restored Republic” (while holding real power) |

| Year Empire began | Republic still legally existed | 27 BC – scholarly consensus |

Modern classics scholars – Ronald Syme, Erich Gruen, Mary Beard, Adrian Goldsworthy – unanimously place the founding of the Principate (the early Roman Empire) in 27 BC.

Why Shakespeare Got It Right (and Why It’s Brilliant Dramatically)

Open any edition of Julius Caesar and search for the word “emperor.” You will not find it once. Not in Brutus’ soliloquy, not in Antony’s funeral oration, not even in Casca’s cynical gossip. Shakespeare deliberately sets the play in the Roman Republic, not the Empire.

This is historically accurate and dramatically essential.

- In Act 1, Scene 2, Casca reports the crown incident: “He put it by with the back of his hand, thus, and then the people fell a-shouting.” The tragedy hinges on the fact that Caesar could have lived had he accepted kingship openly – or refused power altogether.

- Brutus justifies the assassination not because Caesar is a tyrant-emperor, but because “he would be crowned” (2.1.12) – meaning king, the one title Romans could never tolerate.

- Mark Antony’s funeral speech repeatedly calls Caesar “a man” and stresses that he “was my friend, faithful and just to me” – language that would be absurd if Caesar were already an emperor above the law.

When modern productions dress Caesar in imperial purple and laurel wreath as if he were Augustus or Nero, they unintentionally blunt the tragedy. Shakespeare’s Caesar dies precisely because he has not yet crossed the final line into monarchy – and the conspirators believe killing him will save the Republic.

The Real First Emperor: Augustus and the Founding of the Roman Empire

On 16 January 27 BC, Octavian stood before the Senate and announced that he was “restoring the Republic.” In return, the Senate voted him a cluster of powers that made him master of the Roman world while preserving republican forms. They granted him the sacred name Augustus (“revered one”) and confirmed his right to use imperator as a permanent title.

Augustus himself was careful never to call himself emperor. In his Res Gestae Divi Augusti (Deeds of the Divine Augustus), inscribed on bronze pillars outside his mausoleum, he boasts:

“In my sixth and seventh consulships [28–27 BC], after I had extinguished civil wars… I transferred the Republic from my power to the dominion of the Senate and people of Rome.”

This was masterful propaganda. Everyone understood the reality, but the fiction allowed the senatorial class to save face. From that moment, historians date the Roman Empire.

Timeline: From Caesar’s Assassination to the Official Birth of the Empire (44 BC – AD 14)

- 44 BC – Ides of March: Caesar assassinated as Dictator Perpetuo

- 43 BC – Second Triumvirate formed (Antony, Octavian, Lepidus)

- 42 BC – Battle of Philippi; Brutus and Cassius defeated

- 31 BC – Battle of Actium: Octavian defeats Antony and Cleopatra

- 29 BC – Octavian celebrates triple triumph in Rome

- 27 BC – First Constitutional Settlement; title “Augustus” granted → Empire begins

- 23 BC – Second Settlement; Augustus receives tribunicia potestas for life

- AD 14 – Augustus dies; Tiberius succeeds without civil war

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Was Julius Caesar ever called emperor during his lifetime? No. The title did not exist in its later sense. He was hailed as imperator after victories, but so were many generals.

2. Why do so many people still think Caesar was the first emperor? Because he held supreme power and was later deified. His adopted heir Augustus deliberately blurred the lines by calling himself “Divi Filius” (Son of the God) and using Caesar’s name.

3. Did Caesar want to be emperor? He wanted permanent supreme power, but he knew Romans would never accept open monarchy. His strategy was to accumulate republican offices until opposition became impossible.

4. Who was technically the first Roman emperor? Augustus, from 27 BC. Some scholars push it to 31 BC (Actium) or 23 BC, but 27 BC is the overwhelming consensus.

5. Does it really matter if we call Caesar an emperor? Yes – because it distorts both history and Shakespeare. The tragedy of Julius Caesar is the death of the Republic, not the overthrow of a monarch.

6. How does knowing this change our reading of Shakespeare’s play? It makes Brutus’ dilemma genuine rather than delusional, and it turns Antony’s eulogy into a masterful piece of republican rhetoric.

7. What did Romans call their rulers before “emperor”? Consuls, dictators (in emergencies), or simply by name and office. The closest permanent title was princeps (“first citizen”), which Augustus adopted.

Further Reading & Primary Sources

To verify every claim in this article for yourself (as any serious student of Rome or Shakespeare should), here are the most reliable places to go:

Primary Sources (free online with English translations)

- Suetonius, Life of the Divine Julius – especially sections 76–85 (Loeb Classical Library at penelope.uchicago.edu or LacusCurtius)

- Plutarch, Life of Caesar (Parallel Lives) – the most detailed narrative of 44 BC

- Cassius Dio, Roman History Books 43–46

- Cicero’s Philippics (especially 2 and 5) – contemporary speeches that attack Antony but confirm Caesar’s titles

- Appian, Civil Wars Book 2 – the clearest account of the Lupercalia crown incident

- Augustus, Res Gestae Divi Augusti – full text and translation at livius.org or the Forum Romanum site

Best Modern Scholarship

- Adrian Goldsworthy – Caesar: Life of a Colossus (2006) and Augustus: First Emperor of Rome (2014)

- Mary Beard – SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome (2015), chapter “Rome’s First Emperor?”

- Ronald Syme – The Roman Revolution (1939; still the classic analysis of the 27 BC settlement)

- Tom Holland – Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic (2003) – narrative history at its most readable

- Greg Woolf – Rome: An Empire’s Story (2012), chapter 4: “The Principate Begins”

All of the above scholars explicitly state that the Roman Empire as an institution begins with Augustus in 27 BC, not Caesar.

Why Getting This Right Makes You See Both History and Shakespeare More Clearly

Julius Caesar was never an emperor. He was the brilliant, ruthless, charismatic destroyer of the Republic who never quite managed to found the monarchy he effectively exercised. Seventeen years after his blood soaked the floor of the Theatre of Pompey, his adopted son Octavian—now styling himself Imperator Caesar Augustus—achieved what Caesar could not: permanent one-man rule disguised as republican restoration.

Shakespeare understood this perfectly. By refusing to place a single “emperor” in the mouths of Brutus, Cassius, or Antony, he forces us to confront the real tragedy: sixty men with daggers believed they were saving liberty, yet they only cleared the stage for the true architects of autocracy. The Republic died on the Ides of March, but the Empire was not born until 27 BC.