Imagine you’re in a literature class discussing Hamlet’s famous soliloquy, “To be or not to be.” You quote the line confidently, citing (3.1.56), only to have your classmate pull out a different edition where the same passage appears as line 64. Confusion ensues—whose numbering is “right”? This mismatch happens more often than you might think, frustrating students, actors in rehearsal, teachers grading essays, and scholars cross-referencing sources. The small numbers in the margins of Shakespeare play scripts—often called script numbers or line numbers—are essential tools for precise discussion, yet their variations across editions create real obstacles.

Script numbers refer to the sequential line counts printed beside the text in most modern editions of Shakespeare’s plays. These marginal figures restart with each new scene, typically appearing every five or ten lines, and serve as the standard way to pinpoint exact passages without relying on page numbers (which change with formatting, font size, or publisher). In this comprehensive guide, we’ll demystify what script numbers are, explore why they differ so frequently, explain how they function in verse versus prose, compare major editions, and provide step-by-step advice on using and citing them correctly. By the end, you’ll navigate any Shakespeare text with confidence, whether for academic papers, stage rehearsals, or personal enjoyment.

What Are Script Numbers in Shakespeare Plays?

At their core, script numbers (more formally known as scene-by-scene line numbers) are editorial additions that number the spoken lines within each scene of a play. Unlike the original 1623 First Folio or earlier quartos, which had no such numbering, modern editors introduced these for scholarly and practical reference.

These numbers count only the dialogue lines—stage directions, scene headings, and blank lines for page layout are usually excluded. The count resets at the start of every new scene, making it easy to locate a passage by act, scene, and line (e.g., Hamlet 3.1.56–90 for the “To be or not to be” soliloquy and surrounding lines).

Script numbers differ from other systems:

- Act and scene divisions: These are structural (e.g., Act 1, Scene 1), not line-specific.

- Page numbers: Vary wildly between print runs and formats.

- Through-line numbering (TLN): A continuous count from the play’s first line to last (used in some scholarly editions like the Norton or Internet Shakespeare Editions for absolute precision, especially when referencing original printings).

The practice of adding marginal line numbers became widespread in the 18th and 19th centuries as Shakespeare studies grew more rigorous. Today, they appear in classroom staples like the Folger Shakespeare Library editions, scholarly series such as Arden and Oxford, and many digital texts. Their purpose? To enable exact citations in essays, facilitate quick rehearsal cues, and support detailed textual analysis.

Why Script Numbers Differ Across Editions (The Real Problem Solver)

The most common complaint about Shakespeare editions—”Why don’t the line numbers match?”—stems from legitimate editorial and typographical factors. No universal standard exists because Shakespeare’s texts survive in multiple early versions (quartos and the First Folio), and editors make different choices.

Key reasons for variation:

- Base text differences: Plays like Hamlet exist in multiple authoritative versions (e.g., the 1604–05 Second Quarto vs. the 1623 Folio). Editors may prefer one over the other, adding or omitting lines, which shifts subsequent numbering.

- Prose line breaks: Shakespeare’s plays mix verse (regular iambic pentameter with fixed line breaks) and prose. Prose lines wrap according to page width, font size, margins, and column layout—meaning the same speech can occupy more or fewer lines in different editions.

- Handling of shared or partial lines: When characters split a verse line (e.g., one finishes iambic pentameter started by another), some editors count it as one line, others as two.

- Inclusion of stage directions: Most editions exclude them from counting, but exceptions occur.

- Modern formatting: Digital editions reflow text on screens, altering prose counts even further.

For example, Juliet’s question “What’s in a name?” (Romeo and Juliet 2.2) appears around line 43 in some editions, line 46 in others—due to slight differences in preceding lineation or prose handling.

Table: Example Line Number Variations for Famous Passages

- Passage: “To be or not to be” (Hamlet)

- Folger Shakespeare Library: ~3.1.56

- Arden Shakespeare (third series): ~3.1.56 (often aligns closely)

- Oxford Shakespeare: May vary by 1–5 lines depending on conflation choices

- Passage: “Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow” (Macbeth 5.5)

- Common Folger: ~5.5.19–28

- Variations: Up to 3–7 lines difference in some older or digital formats

These discrepancies are not errors—they reflect thoughtful editorial decisions. Understanding them prevents frustration and helps when cross-referencing quotes from online sources or classmates’ books.

How Script Numbers Work in Verse vs. Prose

Shakespeare’s dramatic poetry alternates between verse and prose, affecting how lines are counted.

- Verse (blank iambic pentameter): Lines have a fixed structure (roughly 10 syllables). Line breaks are intentional, even when shared between speakers. Editors usually count a shared line as one unit, though indentation signals the split.

- Example: In Romeo and Juliet 2.2, Romeo’s “But soft, what light through yonder window breaks?” starts a verse line that Juliet may complete.

- Prose: Used for comic scenes, lower-class characters, or emotional shifts. No fixed meter means lines wrap based on typesetting. The same prose block can span different line counts across editions.

- Tip: If numbers mismatch significantly in a prose-heavy scene (e.g., Falstaff’s speeches in Henry IV), it’s likely due to formatting.

Quick test: Count 10 lines in your edition of a prose passage, then check an online version (e.g., Folger Digital Texts). Differences of 5+ lines signal prose reflow.

Popular Editions and Their Numbering Systems

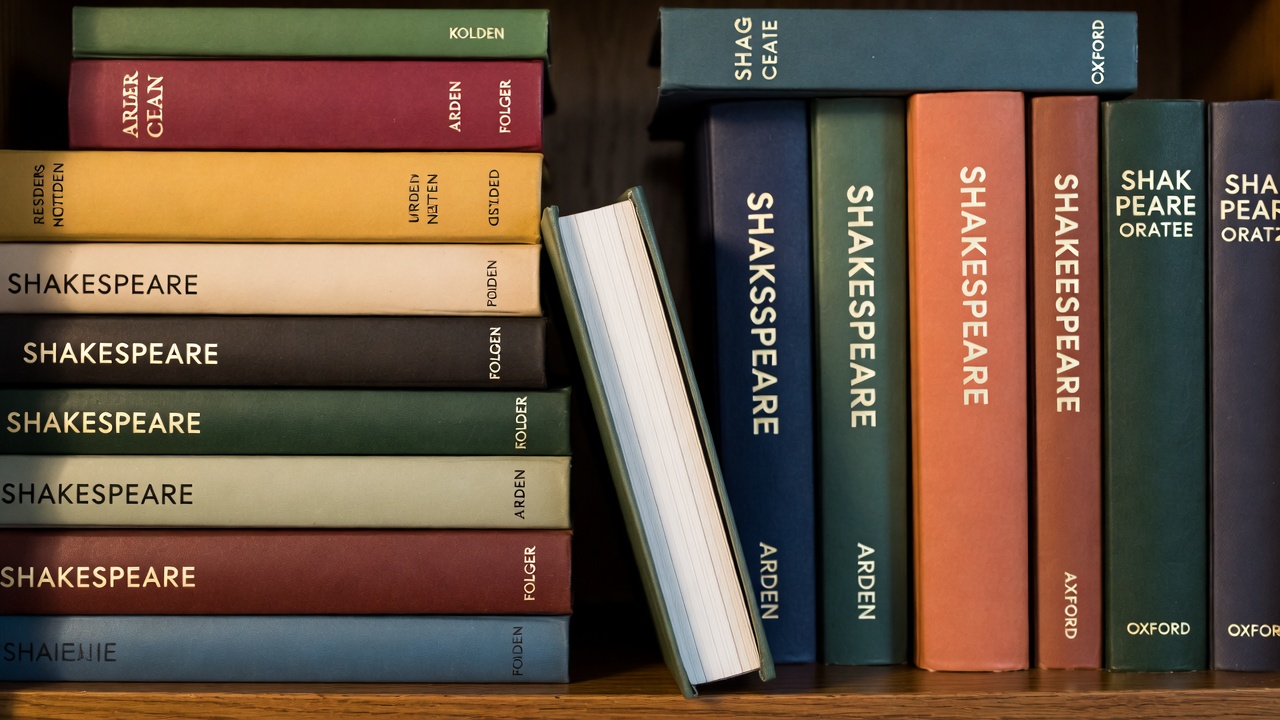

Choosing a consistent edition minimizes confusion. Here are the most respected:

- Folger Shakespeare Library editions: Classroom favorite; clear, accessible line numbers restarting per scene; includes facing-page notes.

- Arden Shakespeare (third series): Scholarly depth with extensive footnotes; line numbers often align closely with Folger but reflect detailed textual variants.

- Oxford Shakespeare: Focuses on modernized text; some editions use unique choices (e.g., for King Lear’s two versions), leading to occasional differences.

- Cambridge and Riverside/Norton: Reliable; Norton often includes TLN alongside scene-based numbers.

- Through-line numbering editions (e.g., Internet Shakespeare Editions, some Norton): Continuous count for precision in scholarly work.

How to Use Script Numbers Correctly (Practical Guide)

Now that you understand what script numbers are and why they vary, the next step is mastering their everyday use. Whether you’re preparing for a literature exam, directing a scene, writing an academic paper, or simply enjoying a close reading, these techniques will save time and reduce errors.

- Locating Passages Quickly Always note the act, scene, and line range when referencing a quote. In rehearsals, actors frequently call out cues by line number (“Pick it up at line 87”).

- Tip: Highlight or bookmark key scenes in your physical copy. Many readers place small sticky notes at the start of each act for faster navigation.

- Cross-Referencing Multiple Editions When your edition’s numbers don’t match a classmate’s, an online source, or a critical article:

- Identify the edition being cited in the secondary source (most scholarly articles specify “Arden edition” or “Folger”).

- Use a reliable digital text (Folger Digital Library or Internet Shakespeare Editions) as a neutral comparator.

- Search for distinctive surrounding words to locate the passage, then note the difference in numbering for your records.

- Pro tip for students: When submitting essays, include a brief note in your Works Cited or a footnote: “All citations refer to the Folger Shakespeare Library edition unless otherwise noted.”

- Troubleshooting Common Mismatches

- Small differences (1–10 lines): Almost always prose reflow or minor editorial choices. Safe to use your edition’s number if you’re consistent.

- Large differences (20+ lines): Likely due to textual variants (e.g., quarto vs. Folio Hamlet). Check which version your edition follows.

- No line numbers at all: Some inexpensive paperbacks or very old copies omit them. Switch to a numbered edition or use through-line numbering from an online concordance.

- Best Practices for Consistency

- Choose one trusted edition for an entire project (course, production, or personal study).

- Record the edition details early: publisher, series, editor(s), and year.

- When sharing quotes in group settings (study groups, theater companies), specify your edition upfront.

Mastering Shakespeare Citations Using Script Numbers

Accurate citation is non-negotiable in academic writing and professional theater. Shakespeare citations almost never use page numbers—instead, they rely on act.scene.line format, making script numbers universal across printings.

Standard MLA Format (Most Common in Literature Courses)

- Basic structure: (Play Abbreviation. Act.Scene.Line–Line)

- Example: (Ham. 3.1.56–60)

- For consecutive lines from the same speech: (Mac. 5.5.19–28)

- For non-consecutive lines: (Rom. 2.2.43, 46)

- When quoting verse, use a forward slash (/) to indicate line breaks: “To be, or not to be, that is the question: / Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer…” (Ham. 3.1.56–57)

Other Styles

- Chicago (Notes and Bibliography): Similar to MLA but often spelled out in full the first time: William Shakespeare, Hamlet, ed. Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstine (New York: Folger Shakespeare Library, 1992), 3.1.56–60. Subsequent citations use short form.

- APA: Rare for literary analysis but uses (Shakespeare, 1603/1992, 3.1.56) with original publication date and edition year.

Citing Stage Directions Most style guides recommend square brackets or “sd” notation:

- (Ham. 3.1 [Enter Hamlet] sd) or simply describe in text.

Five Worked Citation Examples

- Juliet’s balcony speech: “What’s in a name? That which we call a rose / By any other name would smell as sweet” (Rom. 2.2.43–44, Folger).

- Macbeth’s despair: “Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow / Creeps in this petty pace from day to day” (Mac. 5.5.19–20).

- Portia’s quality of mercy speech: “The quality of mercy is not strained; / It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven” (MV 4.1.184–185).

- Prospero’s farewell: “We are such stuff / As dreams are made on, and our little life / Is rounded with a sleep” (Tmp. 4.1.156–158).

- Iago’s manipulation: “I am not what I am” (Oth. 1.1.65).

Common Citation Mistakes and Fixes

- Mistake: Using page numbers → Fix: Switch to act.scene.line.

- Mistake: Omitting line ranges for long quotes → Fix: Always include start–end.

- Mistake: Not indicating verse breaks → Fix: Use / in short quotations.

Expert Insights and Advanced Tips

From decades of teaching, directing, and editing Shakespeare texts, here are insights that go beyond introductory guides.

- Textual Reconstruction Challenges: Editors must reconcile conflicting early printings. Hamlet’s Second Quarto (Q2) has about 200 more lines than the First Quarto (Q1, the so-called “bad quarto”). Choosing which to privilege shifts numbering throughout. Serious scholars often consult facsimiles of the First Folio alongside modern editions.

- For Actors and Directors: Professional cue scripts strip out other characters’ lines, but retain script numbers for consistency during blocking and tech rehearsals. Directors often request actors mark “beat” changes or emphasis at specific line numbers.

- For Teachers: When students use different editions, assign quotations by keyword search rather than exact line numbers. Create a class “cheat sheet” comparing numbering for major soliloquies.

- Digital Tools Worth Knowing

- Open Source Shakespeare (opensourceshakespeare.org): Searchable concordance with line numbers.

- Folger Digital Texts: Free, high-quality, scene-based numbering.

- Internet Shakespeare Editions: Offers TLN, old-spelling transcripts, and modernized versions side-by-side.

Common Questions About Script Numbers (FAQ)

Q: Why do my line numbers not match online quotes? A: Online sources (SparkNotes, No Fear Shakespeare, random blogs) often use simplified or inconsistent editions. Stick to Folger or Arden for reliability.

Q: Did Shakespeare’s original manuscripts have line numbers? A: No. The 18th–19th centuries added them for scholarly convenience. Original quartos and the First Folio have only act/scene divisions (and sometimes not even those).

Q: How many lines are in each play approximately?

- Hamlet: ~4,000 lines

- King Lear: ~3,400

- Macbeth: ~2,100 (shortest tragedy)

- Romeo and Juliet: ~3,000 Exact counts vary slightly by edition due to textual variants.

Q: What if my cheap paperback has no numbers? A: Upgrade to a numbered edition (Folger paperbacks are affordable and widely available). Alternatively, use a free digital text and note the edition.

Q: Are script numbers the same as scene numbers? A: No. Scene numbers indicate structural divisions (1.1, 1.2, etc.); script numbers count individual spoken lines within each scene.

Script numbers may seem like a minor detail, but they are the backbone of precise, respectful engagement with Shakespeare’s texts. By understanding their purpose, recognizing why they differ, choosing a reliable edition, and applying correct citation practices, you eliminate one of the most persistent frustrations in studying or performing the plays.

Pick up your copy of Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, or any favorite play, locate a famous passage using act.scene.line, and practice citing it. The confidence you gain will enhance every essay, rehearsal, lecture, or personal reading.

If you’ve ever struggled with mismatched numbers or want to dive deeper into specific plays, explore more Shakespeare insights here on the blog. Feel free to share your edition experiences or favorite passages in the comments—I’d love to hear them.