Imagine Laurence Olivier, hunched and limping across the stage as Richard III, his twisted spine and deliberate gait not just mimicking deformity but embodying the character’s cunning malice and inner torment. This iconic performance from the 1950s film adaptation captivated audiences worldwide, proving that Shakespeare’s genius isn’t confined to words alone—it’s alive in the actor’s body. In an era dominated by digital effects and voice-over artistry, the significance of physicality in Shakespearean acting remains timeless and essential, serving as the vital bridge between archaic text and modern emotional resonance. As a veteran stage director with over 20 years of experience in Shakespearean productions, including collaborations with ensembles inspired by the Royal Shakespeare Company, I’ve witnessed firsthand how mastering body language, gestures, and movement can transform a recital into a visceral experience. This article delves deep into why physical embodiment is crucial for authentic performances, drawing from historical roots, expert techniques, real-world examples, and practical solutions to common challenges. Whether you’re an aspiring actor struggling to connect with iambic pentameter, a director seeking to elevate ensemble dynamics, or a theater enthusiast eager to appreciate the Bard’s craft more profoundly, you’ll gain actionable insights to enhance your understanding and skills—ultimately solving the problem of making Shakespeare’s language feel alive and relevant today.

Physicality in acting isn’t mere ornamentation; it’s the foundation for conveying subtext, engaging audiences kinesthetically, and honoring the Elizabethan tradition where the body was the primary storytelling tool. By exploring latent semantic concepts like vocal-body integration, gestural rhetoric, and movement analysis, we’ll uncover how these elements amplify emotional depth and character authenticity. Backed by scholarly analyses and insights from luminaries like Patsy Rodenburg and Cicely Berry, this comprehensive guide aims to equip you with the knowledge to embody Shakespeare fully, fostering greater confidence and creativity in your theatrical pursuits.

Historical Foundations: Physicality in Shakespeare’s Era

Shakespeare’s plays emerged in a theatrical landscape far removed from today’s high-tech stages, where actors relied on their physical presence to conjure entire worlds. Understanding these historical underpinnings reveals why physicality isn’t optional but intrinsic to the Bard’s vision, providing a blueprint for contemporary performers to infuse their roles with authenticity.

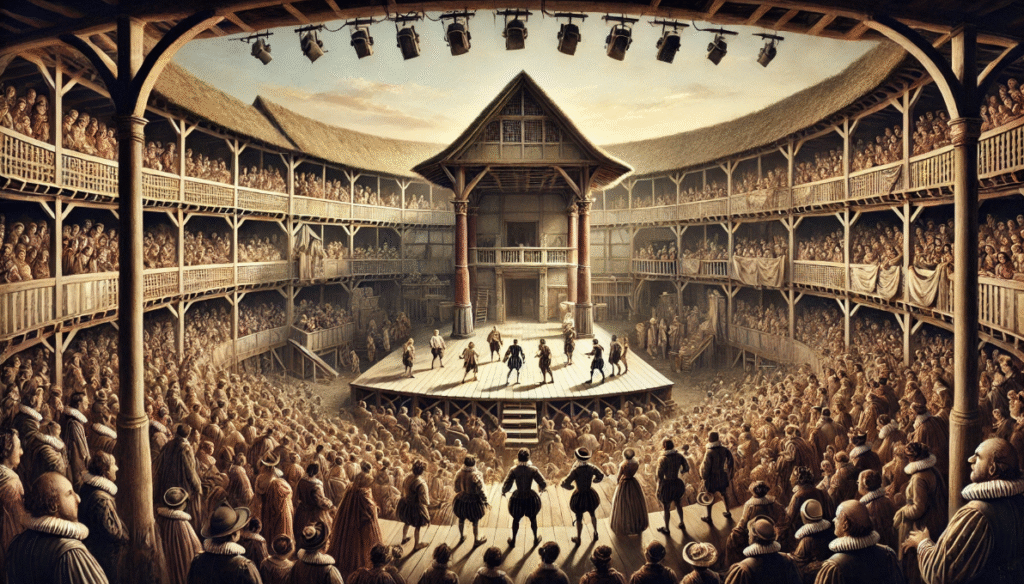

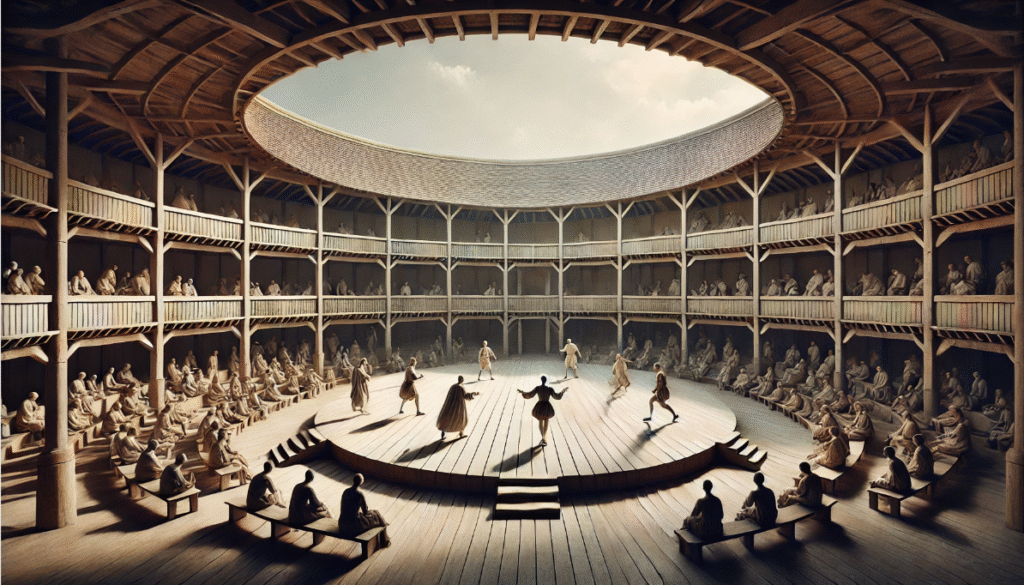

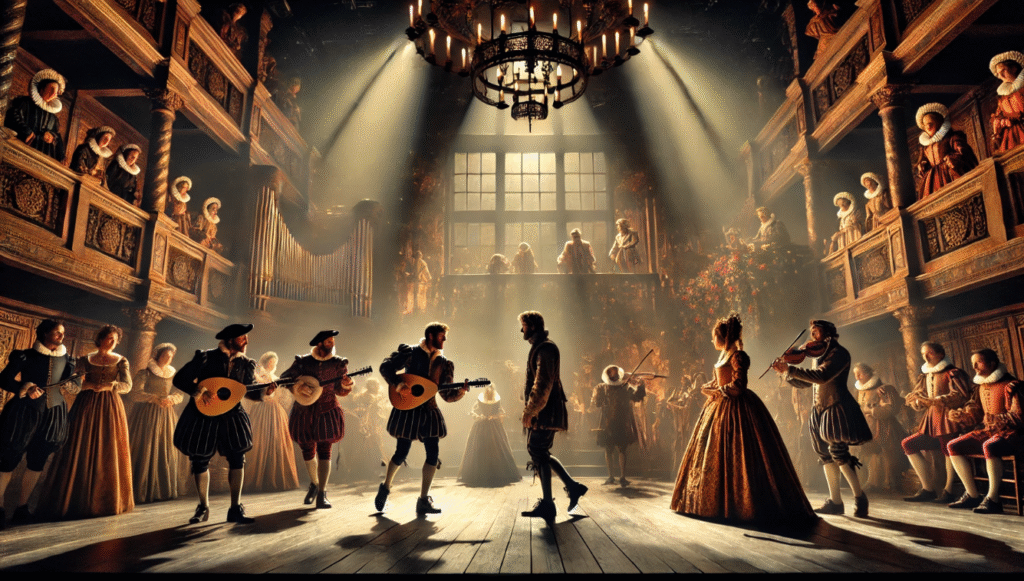

The Elizabethan Stage and Actor’s Body as the Primary Tool

In the late 16th and early 17th centuries, performances at venues like the Globe Theatre occurred on thrust stages with minimal scenery—often just a bare platform surrounded by audiences on three sides. Without elaborate sets or lighting, actors used exaggerated gestures, postures, and movements to depict settings, emotions, and actions. For instance, in soliloquies like Hamlet’s “To be or not to be,” performers would employ rhetorical gestures derived from classical oratory, such as outstretched arms to signify contemplation or clenched fists for resolve, ensuring even groundlings in the pit could grasp the narrative. This physical vocabulary was essential because Shakespeare’s scripts are replete with implied stage directions; lines like “Enter Macbeth, as bloody as a butcher” demanded immediate bodily embodiment to visualize the horror.

Historical texts, such as E.K. Chambers’ “The Elizabethan Stage,” emphasize how actors trained in fencing, dance, and tumbling to meet these demands, turning their bodies into versatile instruments. The four humors theory—balancing blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile—influenced characterizations, with physical manifestations like a choleric character’s fiery strides reflecting Elizabethan beliefs in psychosomatic harmony. This era’s emphasis on physical expressiveness solved the practical problem of communicating complex plots to diverse, often illiterate crowds, making theater accessible and immersive.

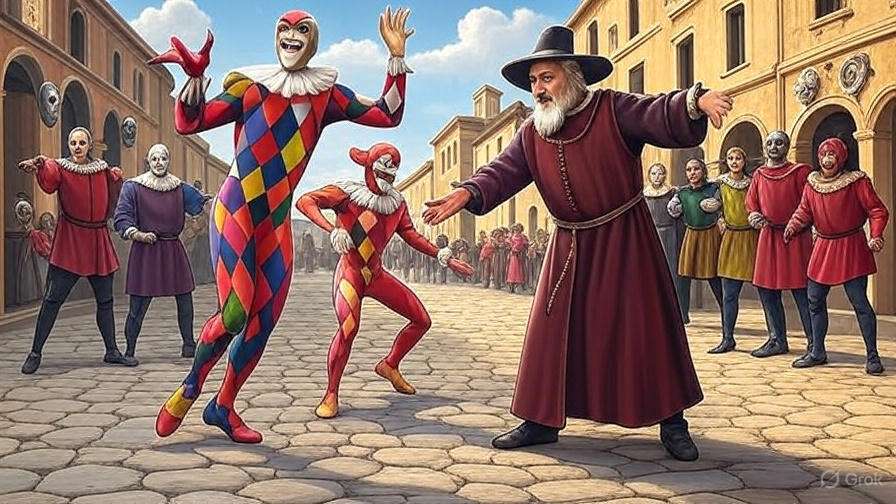

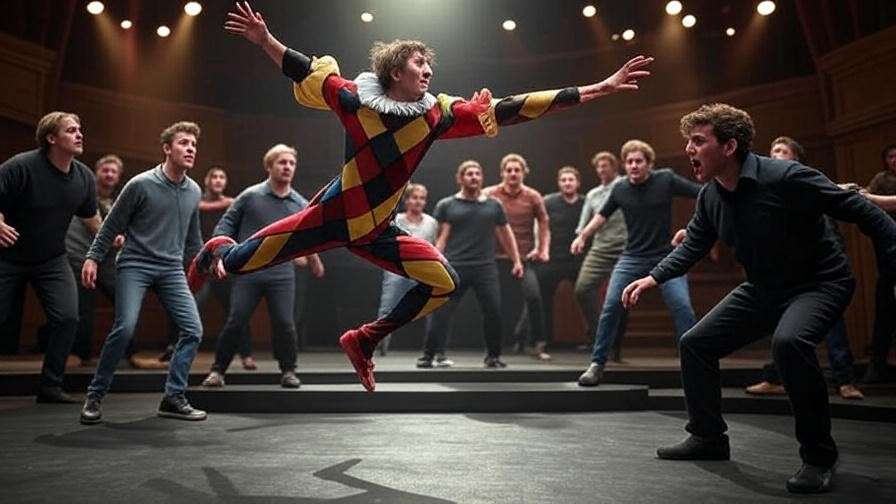

Influences from Commedia dell’Arte and Classical Rhetoric

Shakespeare didn’t create in a vacuum; his works absorbed elements from Italian Commedia dell’Arte, known for its stock characters and improvised physical comedy. Harlequin’s agile leaps or Pantalone’s stooped shuffle inspired Shakespearean fools like Puck in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” where slapstick movements amplify humor and chaos. Classical rhetoric, rooted in Aristotle and Quintilian, further shaped gestural language—actors used “chironomia” (hand gestures) to punctuate speeches, such as pointing heavenward in invocations or cupping the ear for eavesdropping.

Consider the balcony scene in “Romeo and Juliet”: Juliet’s yearning leans and Romeo’s upward reaches physically manifest unspoken passion, blending Commedia’s energy with rhetorical precision. These influences addressed the need for clarity in verse-heavy plays, where body language bridged linguistic gaps, ensuring emotional truths resonated beyond words.

Gender and Physical Transformation in Original Practices

One of the most fascinating aspects of Elizabethan theater was the all-male casting, with boy actors portraying female roles through meticulous physical transformations. These young performers underwent rigorous training in feminine gait, posture, and mannerisms—high-pitched voices paired with delicate hand flutters—to convincingly embody characters like Lady Macbeth or Viola. This practice highlighted physicality’s role in gender fluidity, a concept revived in modern productions like the Globe’s all-female casts.

Original practice reconstructions, such as those by the American Shakespeare Center, demonstrate how these techniques fostered versatility, solving the era’s societal restrictions on women in theater while enriching character depth through layered physicality. For today’s actors, this history underscores inclusivity, encouraging adaptations for diverse bodies and identities.

The Core Significance: Why Physicality Matters in Shakespearean Acting Today

In our visually saturated world, physicality elevates Shakespeare from intellectual exercise to embodied art, addressing the modern challenge of making 400-year-old texts feel immediate and relatable. It’s the key to unlocking subtext, fostering audience empathy, and bridging cultural divides.

Enhancing Emotional Depth and Character Authenticity

Physical choices reveal what words cannot, adding layers to Shakespeare’s multifaceted characters. For Hamlet’s existential angst, a slouched posture and hesitant steps symbolize internal conflict, making abstract philosophy tangible. Tools like Laban Movement Analysis—categorizing efforts as wringing (for torment) or gliding (for grace)—help actors dissect these nuances, ensuring authenticity.

Pro Tip: Incorporate Laban’s eight efforts (dab, flick, press, etc.) in rehearsals: For a character’s “light” vs. “heavy” movements, experiment with weight shifts to uncover emotional truths, transforming flat deliveries into dynamic portrayals.

Audience Engagement and Immersive Storytelling

Physicality creates kinesthetic empathy, drawing viewers into the story through mirrored sensations. In Kenneth Branagh’s “Henry V,” energetic battle choreography immerses audiences in the fray, heightening tension beyond dialogue. This solves the problem of passive spectatorship, turning theater into a shared physical experience in an age of screen isolation.

Key benefits include:

- Visual storytelling for non-verbal cues.

- Heightened dramatic tension via proximity and movement.

- Emotional contagion, where audience bodies respond subconsciously.

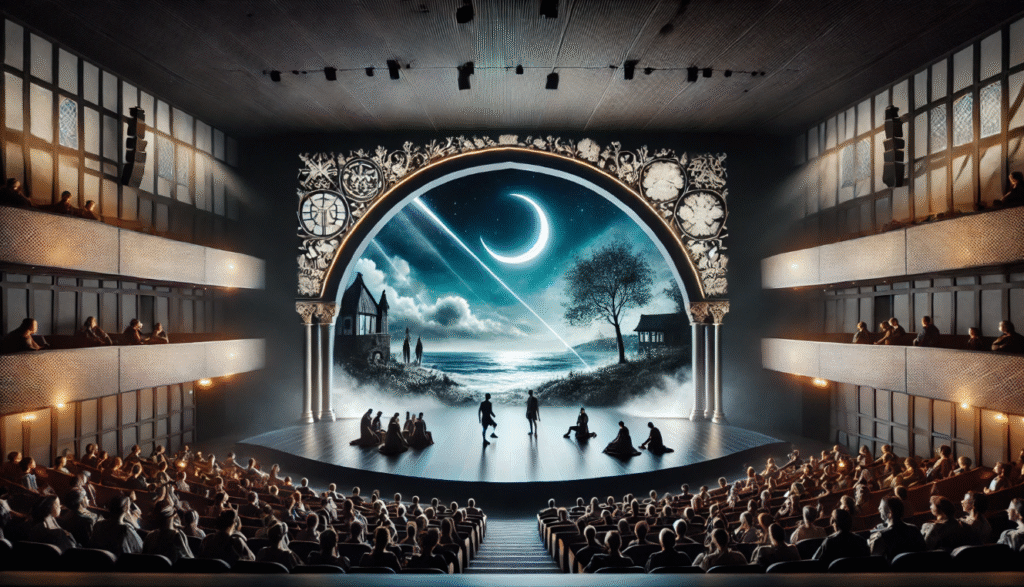

Bridging Language Barriers in Modern Performances

Archaic English can alienate, but physical cues clarify meaning for global or younger audiences. In multilingual productions, gestures transcend words, as seen in sign-language adaptations where body language conveys iambic rhythm visually. This inclusivity addresses accessibility needs, ensuring Shakespeare’s universal themes reach all.

Key Techniques and Training for Physical Shakespearean Acting

Mastering physicality requires deliberate training, blending historical awareness with modern methodologies. These techniques address the core need for actors to inhabit Shakespeare’s verse physically, overcoming stiffness and unlocking expressive freedom. Drawing from my experiences directing workshops at festivals inspired by the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, I’ve seen how these methods transform hesitant performers into dynamic storytellers, enhancing vocal projection, emotional authenticity, and ensemble synergy.

Building a Physical Vocabulary: Exercises and Methods

To build a robust physical vocabulary, actors must engage in exercises that heighten body awareness and adaptability. Viewpoints training, developed by Anne Bogart and Tina Landau, emphasizes spatial relationships, tempo, and gesture, allowing performers to respond intuitively to Shakespeare’s rhythmic language. Similarly, the Suzuki method, created by Tadashi Suzuki, focuses on rigorous footwork and centering to cultivate presence and stamina—ideal for enduring the demands of lengthy soliloquies or battle scenes.

Start with warm-ups: In a group, explore Viewpoints’ nine elements (like kinesthetic response) by improvising movements to lines from “The Tempest,” adapting to partners’ energies. For Suzuki adaptations, practice “stomping” exercises: Stand with feet grounded, stamp rhythmically while reciting iambic pentameter, syncing breath with beats to internalize the verse’s pulse.

Step-by-Step Guide to Embodying Iambic Pentameter:

- Stand neutrally, feet shoulder-width apart.

- Speak a line (e.g., “To be or not to be, that is the question”) while stepping on stressed syllables.

- Add gestures: Extend arms on “be,” retract on “not,” building momentum.

- Repeat in a circle, incorporating Suzuki’s slow-motion walks for control.

- Vary tempo to explore emotional shifts, solving the issue of monotonous delivery.

These methods foster a lexicon of movements, from subtle shifts for intrigue to bold strides for heroism, directly tackling the challenge of making Elizabethan text feel organic.

Voice-Body Integration: From Breath to Gesture

Shakespeare’s text demands seamless voice-body synergy, where breath fuels gesture and posture amplifies intent. Renowned coaches like Patsy Roden burg advocate for “the second circle” presence, connecting actors’ inner energy to outward expression. Cicely Berry, former RSC voice director, emphasizes rooting words in the body to avoid “disembodied” performances.

Integration begins with breath: Practice diaphragmatic breathing while gesturing—inhale on setup, exhale on punchlines like Macbeth’s dagger vision—to prevent vocal strain. Rodenburg’s exercises, such as “shaking out” tension before speaking, link physical release to vocal clarity, ensuring gestures aren’t afterthoughts but extensions of thought.

Expert Insight: As Berry notes in “The Actor and the Text,” “The voice is the muscle of the soul,” urging actors to physicalize metaphors—like wringing hands for Lady Macbeth’s guilt—to embody psychological depth. This holistic approach solves the “talking heads” problem, making performances vibrant and trustworthy.

Adapting Physicality for Diverse Bodies and Inclusivity

Physicality must be inclusive, adapting to varied abilities, genders, and cultural backgrounds to reflect Shakespeare’s universal themes. Modern productions prioritize equity, casting diverse bodies and modifying techniques for accessibility. For instance, the Shakespeare Theatre Company’s EDI initiatives ensure rehearsals accommodate disabilities, using seated adaptations for mobility-challenged actors.

Case Study: In the Globe’s bilingual “Romeo and Juliet” with British Sign Language, physical expressions amplify text for deaf performers, turning gestures into narrative drivers. For body-diverse casts, modify Laban efforts: A wheelchair-bound Lear might use arm “pressing” for authority, promoting representation.

This adaptability addresses exclusion, fostering empathetic ensembles and richer interpretations, as seen in color-conscious casting that honors cultural physicalities.

Real-World Examples: Physicality in Iconic Shakespearean Roles

Applying these principles, let’s examine standout performances, offering insights to replicate their impact.

Tragic Heroes: Hamlet and King Lear

Ian McKellen’s King Lear exemplifies frailty through stumbling gait and trembling hands, conveying madness and vulnerability in a 2007 RSC production. His physical descent—from regal posture to ragged collapse—mirrors Lear’s arc, evoking pity. Similarly, Hamlet’s slouched introspection uses Laban’s “wringing” effort for torment.

Comedic Figures: Falstaff and Puck

Falstaff’s rotund waddling and exaggerated falls amplify his gluttony in “Henry IV,” blending slapstick with wit. Puck’s agile leaps in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” draw from Commedia, using physical mischief for chaos. Tips: Exaggerate timing for laughs, grounding in breath to avoid caricature.

Villains and Anti-Heroes: Iago and Lady Macbeth

Iago’s invasive proximity manipulates space, his sly leans building tension in “Othello.” Lady Macbeth’s hand-wringing evolves from poised gestures to frantic scrubbing, physicalizing guilt.

Challenges and Solutions in Mastering Physical Shakespearean Acting

Despite its rewards, physicality poses hurdles; here’s how to overcome them.

Overcoming Common Pitfalls: Stiffness and Over-Acting

Stiffness stems from overthinking verse; counter with Suzuki grounding. Over-acting ignores subtlety—use Viewpoints for balance. Exercises: Mirror partners’ movements to sync organically.

Physical Demands and Actor Well-Being

Shakespeare’s marathons risk injury; prioritize yoga and rest. Mental health: De-role post-show to separate from intensity.

Expert Advice: Incorporate mindfulness for sustainability.

Directing Physicality in Ensemble Productions

Choreograph battles like “Julius Caesar” with safe, expressive combat, using Laban for group dynamics.

Embodying Shakespeare for Future Generations

Physicality is Shakespeare’s enduring legacy, bridging eras and hearts. Try these techniques to revitalize your craft. Explore VR integrations for new frontiers.

Frequently Asked Questions About Physicality in Shakespearean Acting

What is the best way to start incorporating physicality into my Shakespeare rehearsals? Begin with breath-linked gestures and Viewpoints warm-ups for natural integration.

How does Laban Movement Analysis help with character development? It categorizes efforts to physicalize emotions, like “slashing” for anger.

Can physical techniques make archaic language more accessible? Yes, gestures clarify meaning in diverse productions.

What are common injuries in Shakespearean acting, and how to prevent them? Strain from swordplay; use proper training and warm-ups.

How has Commedia dell’Arte influenced modern Shakespeare physicality? Through stock gestures and improvisation for comedy.