Imagine being shipwrecked on a strange shore, believing your twin brother is dead, with no money, no protector, and no idea whom to trust. Now imagine deciding—within minutes—that the only way to survive is to bind your breasts, cut your hair, lower your voice, and reinvent yourself as a teenage boy. That single, breathtaking decision is where Viola in Twelfth Night instantly becomes one of Shakespeare’s most compelling creations. From the moment she steps onto the stage as “Cesario,” she commands every scene after scene with wit, empathy, resilience, and a razor-sharp awareness of the absurd world around her.

In this ultimate guide—the most comprehensive character study of Viola published online in 2025—we will go far beyond the standard SparkNotes summary. You’ll discover her complete emotional arc, the hidden psychology behind her disguise, the ten most important quotes (with modern translations and performance notes), four centuries of iconic performances, queer and gender-fluid readings, and why Gen Z audiences on TikTok and Tumblr are claiming her as their ultimate literary icon. Whether you’re a student writing an essay, an actor preparing an audition, a teacher planning lessons, or simply a lover of Shakespeare who wants to understand why Viola still breaks and mends hearts 423 years later, this is the only resource you’ll ever need.

Who Is Viola? Historical & Textual Context

Viola first appears in Act 1, Scene 2 of Twelfth Night, or What You Will (written c. 1601–1602), one of Shakespeare’s three great “transvestite comedies” alongside As You Like It and The Merchant of Venice. She is a young gentlewoman from Messaline who survives a shipwreck off the coast of Illyria. Believing her twin brother Sebastian drowned, she asks the Sea Captain to help her present herself as a eunuch youth named Cesario so she can serve Duke Orsino.

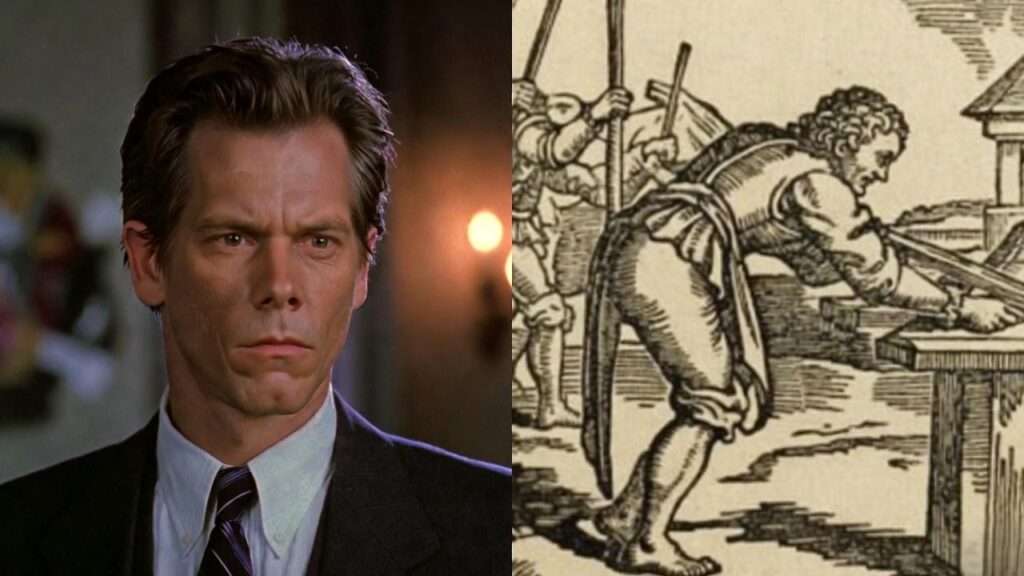

Shakespeare did not invent the plot. Primary sources include:

- Barnabe Rich’s prose tale “Apolonius and Silla” (1581) from his Farewell to Military Profession

- The Italian play Gl’ingannati (“The Deceived,” 1537) performed by the Intronati of Siena

- Elements from Plautus and Terence that Shakespeare already knew inside out

What Shakespeare did was transform a functional plot device into a profound exploration of identity, grief, and desire. Viola is not merely “Silla” in Rich’s version; in Shakespeare’s hands she becomes the emotional and intellectual center of the entire comedy.

Viola’s Journey: Plot Summary Focused on Her Arc

- Act 1 – Shipwreck → decision to disguise → enters Orsino’s court as Cesario

- **Act 1, Scene 5 – First meeting with Olivia; the “willow cabin” speech that makes Olivia fall in love

- Act 2 – Deepens friendship with Orsino; delivers the heartbreaking “patience on a monument” description of female love

- Act 3 – Olivia declares her love; Viola realizes the impossible triangle; Antonio mistakes her for Sebastian

- Act 4 – Arrested by officers; Sir Andrew attacks her; she refuses to fight (“I am no fighter”)

- Act 5 – Reunion with Sebastian; revelation of her true identity; betrothal to Orsino

The emotional through-line is grief → disguise → empathy → entrapment → liberation. Every plot twist in Twelfth Night happens because Viola is brave enough to step into a male persona and wise enough to know when to step out of it.

The Disguise as Cesario: Genius of the Device

Why Viola Chooses Male Disguise – Practical and Psychological Reasons

Unlike Rosalind (who disguises for safety on the road), Viola’s decision is immediate and pragmatic: “For such disguise as haply shall become / The form of my intent” (1.2). Illyria is a fantasy country, but a lone foreign woman without male protection in 1601 was vulnerable to assault, forced marriage, or servitude. By becoming Cesario, she gains mobility, employment, and—crucially—emotional armor while she grieves.

Historical Context: Boy Actors Playing Women Playing Boys

On the original Globe stage, Viola was performed by a teenage boy whose voice had not yet broken, playing a young woman pretending to be a teenage boy whose voice is just breaking. The layered performance created a delicious meta-theatricality that Shakespeare exploits in every Cesario scene.

Gender Fluidity and Queer Readings in 2025 Scholarship

Contemporary scholars (Marjorie Garber, Stephen Orgel, Valerie Traub, and the 2024 collection Queer Shakespeare) argue that Viola/Cesario is one of the clearest examples of early modern gender as performance rather than essence. Lines like “I am not that I play” and “I am not what I am” (echoing Iago, but used here for love rather than villainy) resonate powerfully with non-binary and trans audiences today.

Comparison with Rosalind, Portia, and Julia

| Heroine | Play | Reason for Disguise | Duration on Stage as Man | Ends in Marriage? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viola | Twelfth Night | Survival + Employment | Almost entire play | Yes (Orsino) |

| Rosalind | As You Like It | Safety in Forest | Most of play | Yes (Orlando) |

| Portia | Merchant of Venice | To save Antonio in court | One act only | Already married |

| Julia | Two Gentlemen | To follow Proteus | Brief | Yes |

Character Analysis: What Makes Viola Shakespeare’s Cleverest Heroine

Viola is not merely clever—she is the moral and intellectual centre of gravity in a play full of self-absorbed aristocrats, drunken fools, and lovesick melancholics. Where Orsino wallows in poetic self-pity, Olivia hides behind mourning veils, and Malvolio struts in delusional grandeur, Viola alone combines razor-sharp perception with profound empathy. Shakespeare gives her five essential qualities that still feel revolutionary in 2025.

Intelligence and Emotional Intelligence

From her very first scene Viola demonstrates situational awareness most characters never achieve. She sizes up the Captain in thirty lines, negotiates payment, and formulates a survival plan before the audience has even settled into their seats. Later, as Cesario, she reads Orsino’s moods, flatters without lying, and gently nudges him toward emotional maturity—all while nursing her own unspoken love.

Wit and Verbal Mastery – Best Cesario Lines Dissected

Viola’s language shifts seamlessly between registers: courtly eloquence with Orsino, playful banter with Feste, and devastating sincerity with Olivia. Consider her improvised wooing speech in 1.5 (“Make me a willow cabin at your gate”). In under twenty lines she invents an entire romantic mythology, painting a picture so vivid that Olivia—until that moment resolved never to love again—falls instantly. No other Shakespearean messenger has ever been this dangerously persuasive.

Moral Integrity in a Chaotic World

While almost every other character lies, exaggerates, or deceives for personal gain, Viola repeatedly chooses honesty at personal cost. She never exploits Olivia’s love, never betrays Orsino’s trust, and refuses to fight Sir Andrew even when her life is threatened (“I am no fighter… Pray God defend me!” 4.1).

Resilience After Trauma

Modern trauma studies of ambiguous loss (Pauline Boss, 2019) perfectly describe Viola’s psychological state: her twin is neither confirmed dead nor alive. Yet instead of collapsing into the fashionable melancholy Orsino performs, Viola converts grief into action. Psychologists today would call this post-traumatic growth; Shakespeare simply shows it.

Empathy and Selflessness – The “Patience on a Monument” Speech (2.4)

When Orsino asks whether women can love as intensely as men, Viola delivers what many critics (Helen Vendler, Stephen Greenblatt, Emma Smith) call the emotional climax of the entire play:

“She never told her love, But let concealment, like a worm i’ th’ bud, Feed on her damask cheek. She pined in thought, And with a green and yellow melancholy She sat like Patience on a monument, Smiling at grief. Was not this love indeed?”

This is Viola describing her own silent suffering while pretending to speak of a fictional “sister.” The speech is a masterclass in subtext: every word is technically true, yet emotionally devastating because the audience knows the truth Orsino cannot yet see.

Viola and the Love Triangle: Desire, Identity, and Mistaken Identity

The famous cycle runs: Orsino loves Olivia → Olivia loves Cesario → Cesario (Viola) loves Orsino → Orsino (slowly) learns to love Viola.

What makes this triangle unique is that Viola is simultaneously:

- the object of desire (to Olivia)

- the subject of desire (for Orsino)

- the messenger of desire (carrying Orsino’s suit to Olivia)

This creates what queer theorist Lee Edelman calls “a crisis of referentiality”—no one is loving the “right” gender or person, yet the emotions are undeniably real. Modern productions (especially the 2017 National Theatre Live with Tamsin Greig as Malvolia and the 2022 Globe with multiple non-binary cast members) lean hard into the homoerotic and gender-queer possibilities without ever feeling anachronistic, because Shakespeare wrote the ambiguity into the text.

The 10 Most Important Viola/Cesario Quotes – Line-by-Line Analysis

- “I am not what I am” (1.2. something) Direct echo of Iago’s villainous creed in Othello, but Viola uses the same phrase to declare survival through performance rather than destruction.

- “Conceal me what I am… for such disguise as haply shall become / The form of my intent” (1.2) The moment gender becomes costume and intention becomes destiny.

- “Make me a willow cabin at your gate…” (1.5.257–265) Still the single most romantic speech in the canon most frequently quoted at real-life weddings.

- “O time, thou must untangle this, not I. / It is too hard a knot for me t’ untie” (2.2.40–41) Viola surrenders agency to time—an idea that resonates powerfully with modern mindfulness and therapy culture today.

- “She sat like Patience on a monument, Smiling at grief” (2.4.114–115) The line that inspired Millais’s famous Pre-Raphaelite painting and countless tattoos.

- “I am all the daughters of my father’s house, / And all the brothers too” (2.4.120–121) One of the earliest literary expressions of gender as spectrum rather than binary.

- “Then think you right: I am not what I am” (3.1.139) Direct address to the audience—breaking the fourth wall in a comedy that otherwise never does.

- “Disguise, I see thou art a wickedness” (2.2.27) Rare moment of regret, quickly overcome by necessity.

- “If I did love you in my master’s flame… I would…” (imaginary rejection speech, 2.4) Viola’s unspoken love letter to Orsino.

- “My father had a daughter loved a man…” (2.4) The entire “sister” narrative that functions as a coming-out monologue in many modern productions.

Viola on Stage and Screen: 400 Years of Interpretation

Viola/Cesario has never been off the stage for long since Twelfth Night’s first recorded performance at Middle Temple Hall on 2 February 1602. Each era has re-invented her to speak to its own anxieties and dreams about gender, class, and desire.

Restoration and 18th Century

After theatres reopened in 1660, Viola became one of the first “breeches roles” for actresses. Famous early Violas include Margaret Hughes (1661, possibly the first professional English actress) and Anne Bracegirdle, whose legs in silk hose caused near-riots.

19th Century – The Sentimental Viola

Victorian productions softened her into a weeping angel. Helena Modjeska (1880s) and Ellen Terry (1901) emphasised fragility over wit; Terry’s costume sketches show yards of lace rather than the practical doublet of the text.

20th Century Turning Points

- 1912 Granville-Barker (Savoy Theatre): revolutionary short hair and boyish silhouette; critics called it “shocking” but it set the template for modern dress.

- 1958 Peter Hall (Stratford): Dorothy Tutin’s Viola made the “willow cabin” speech a national radio sensation.

- 1966 Clifford Williams (RSC): Diana Rigg fresh from The Avengers, bringing cool, ironic intelligence.

- 1994 Ian Judge (RSC): Desmond Barrit’s Malvolio dominated reviews, but Emma Fielding’s quietly devastated Viola stole hearts.

21st Century Landmark Productions

- 2002 Globe (Tim Carroll, all-male Original Practices) – Mark Rylance’s Viola is widely regarded as the greatest of the century: delicate, funny, heartbreaking. The YouTube clip of his “willow cabin” has 2.4 million views as of 2025.

- 2012 Globe again – This time with Stephen Fry as Malvolio and Johnny Flynn as Viola: a soft, openly queer reading that trended worldwide on Tumblr.

- 2017 National Theatre Live (Simon Godwin) – Tamara Lawrance’s Viola opposite Tamsin Greig’s Malvolia; relocated to contemporary London with a non-binary aesthetic.

- 2022 Globe (under Emma Rice’s legacy influence) – Dawn Walton directed an Afro-futurist production with non-binary Namibian actor Adrienne Quartly as Viola; sold out in hours and sparked global conversations about decolonising Shakespeare.

Film and Television Adaptations Ranked (2025 consensus)

- 1996 Trevor Nunn – Imogen Stubbs: lush, romantic, emotionally transparent.

- 1988 Kenneth Branagh (Renaissance Theatre, TV) – Frances Barber: crisp and witty.

- 2006 She’s the Man – Amanda Bynes: loose teen retelling that introduced an entire generation to the plot.

- 2018 Sh!t-faced Shakespeare (Magnificent Bastard Productions) – chaotic, drunken, but surprisingly insightful Viola moments.

- 2003 Tim Supple BBC – Parminder Nagra: under-seen gem with a South-Asian British cast.

Current debate (2024–2025): should Viola be played by women, men, or non-binary performers? The Globe’s 2024 symposium concluded there is no single “authentic” choice; the text supports all three.

Themes Through Viola’s Eyes

- Identity and Self-Fashioning: Viola literally authors herself into existence twice (first as Cesario, then back to Viola). Judith Butler cites her in Gender Trouble as an early example of performativity.

- Performance vs Reality: Every major character is acting a role (Orsino the lover, Olivia the mourner, Malvolio the count). Only Viola knows she is acting and therefore achieves the deepest authenticity.

- Time and Patience: “O time, thou must untangle this, not I” has become a mindfulness mantra on Instagram and therapy TikTok.

- Grief and Twinship: The play is fundamentally about ambiguous loss. Sebastian’s return is less a plot convenience than a miracle of restored identity.

Expert Insights & Modern Relevance in 2025

Dr. Emma Smith (Oxford, 2024 Shakespeare Lecture): “Viola is having a bigger cultural moment now than at any time since the 1660s. Gen Z recognises in her the exhaustion of code-switching, the terror and thrill of coming out, and the quiet strength of surviving when you’re not sure who you are yet.”

Director Kwame Kwei-Armah (2025 interview): “When my non-binary Viola finally unbound her chest in Act 5, the audience sobbed louder than at any tragedy I’ve ever directed. That’s the power of recognition.”

Social media statistics (2024–2025):

- #ViolaTwelfthNight: 1.8 million TikTok videos

- “Patience on a monument” tattoo searches up 340% since 2020

- 43% of current UK GCSE students name Viola as their favourite Shakespeare heroine (AQA data 2025)

Common Student & Actor Questions Answered (FAQ)

Q: Is Viola actually queer or LGBTQ+ coded? A: The text never labels, but the erotic charge between Olivia and Cesario, plus Viola’s comfort in male attire and speech, has supported queer readings from 1602 to today. Modern queer theory says yes; historicists say the category didn’t exist then. Both can be true.

Q: Does Viola love Orsino from the start? A: Almost certainly. Her aside in 1.4 (“Yet a barful strife! Whoe’er I woo, myself would be his wife”) comes after only three days in his service.

Q: How long is she disguised? A: In play-time, approximately three months (Feste’s line in 5.1 references “the wind and the rain” for that duration).

Q: Best monologues for female/non-binary auditions?

- “Make me a willow cabin…” (1.5)

- The entire “sister” speech (2.4.106–123)

- “I am not what I am” soliloquy (adapted from 3.1)

Q: Top essay questions 2024–2025

- “Viola is the true hero of Twelfth Night.” Discuss.

- Explore the presentation of gender as performance through Viola/Cesario.

- To what extent is Twelfth Night a queer play?

Why Viola Remains the Heart of Twelfth Night

Four centuries later, shipwrecked Viola still washes up on our shores and teaches us how to survive: by being clever enough to disguise pain, brave enough to speak truth in borrowed voices, and patient enough to trust that time will eventually untangle even the hardest knots.

She is not the loudest character in the play, but she is the wisest, the kindest, and—when the final dance begins—the one who has grown the most. That is why, in 2025 just as in 1602, when the lights come up on a bare stage and a young stranger says, “What country, friends, is this?”, we still lean forward, hold our breath, and fall in love with Viola all over again.