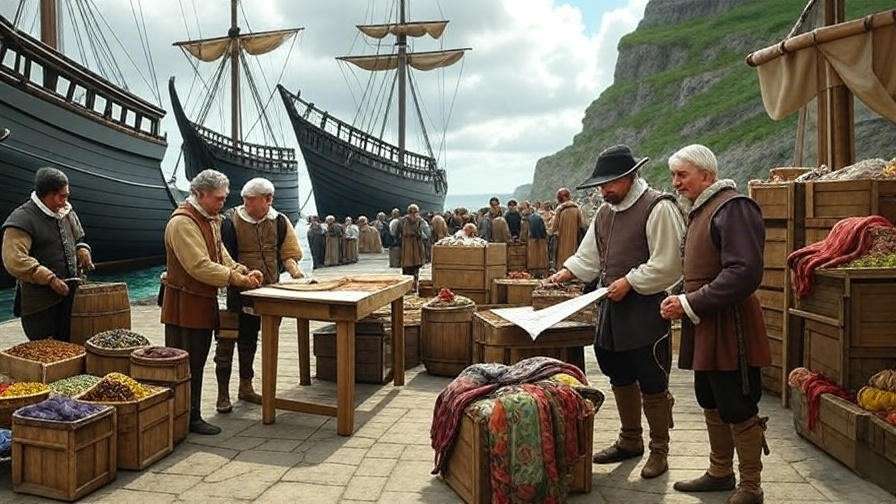

Picture a bustling Elizabethan marketplace: merchants haggle over exotic silks, seal deals with a handshake, and stake their reputations on bonds of trust. In William Shakespeare’s world, merchants bonding was more than a financial transaction—it was a complex dance of trust, risk, and human connection that defined trade and society. For readers, students, and scholars, understanding merchants bonding in Shakespeare’s plays unlocks profound insights into Elizabethan commerce and timeless lessons about relationships. This article explores how Shakespeare uses merchant bonds to reflect trust, economic interdependence, and moral dilemmas, offering value for both literary enthusiasts and modern professionals. As a Shakespearean scholar with years of research into Elizabethan literature, I’ll guide you through this fascinating theme with textual evidence and historical context.

What Is Merchants Bonding in Shakespeare’s Context?

Defining Merchants Bonding

Merchants bonding in Shakespeare’s works refers to the financial, social, and emotional agreements that bind traders in commerce. These bonds often involve loans, contracts, or mutual reliance, reflecting the economic realities of Elizabethan England. In plays like The Merchant of Venice, bonds are literal (e.g., Antonio’s loan from Shylock) and symbolic, representing trust and obligation. Historically, merchants in Venice and London relied on credit systems, where reputation and personal relationships underpinned financial deals. This concept resonates with modern notions of business partnerships, where trust remains a cornerstone.

Shakespeare’s World: The Merchant Class in Elizabethan Society

In the late 16th century, England’s merchant class was rising in prominence, fueled by global exploration and trade. Merchants in London’s markets or Venice’s Rialto (a frequent setting in Shakespeare’s plays) were pivotal to economic growth. Shakespeare, himself a savvy investor, was familiar with these dynamics, owning shares in the Globe Theatre and engaging in property deals. His plays reflect the merchant class’s influence, portraying them as ambitious yet vulnerable to economic risks like shipwrecks or debt defaults. According to Dr. Stephen Greenblatt, a renowned Shakespearean scholar, “Shakespeare’s fascination with commerce mirrors the era’s obsession with wealth and risk” (Greenblatt, 2004).

Merchants Bonding in Key Shakespearean Plays

The Merchant of Venice: Trust and Betrayal in Bonds

In The Merchant of Venice, merchants bonding drives the central conflict. Antonio, a Venetian merchant, secures a loan from Shylock, pledging a “pound of flesh” as collateral (Act 1, Scene 3). This bond tests trust and loyalty, as Antonio’s ships face peril, and Shylock demands repayment. Shakespeare uses this relationship to explore economic risk and personal sacrifice. For instance, Antonio’s willingness to risk his life for Bassanio’s courtship highlights the emotional depth of merchant bonds. The play’s famous trial scene (Act 4, Scene 1) underscores the tension between justice and mercy, with the bond as a metaphor for societal values.

The Comedy of Errors: Mistaken Identities and Mercantile Trust

In The Comedy of Errors, merchant bonds propel the plot through misunderstandings over payments. Egeon, a merchant, faces execution over an unpaid debt in Ephesus, while his sons’ mistaken identities cause chaos in trade dealings. Shakespeare illustrates how trust in commerce relies on clear communication and reputation. For example, when Antipholus of Syracuse is mistaken for his twin, merchants demand payments he doesn’t owe, showing how fragile mercantile trust can be (Act 2, Scene 2). This play highlights the comedic yet critical role of bonds in maintaining economic stability.

Other Plays: Merchants Bonding in Broader Contexts

Merchant themes appear in other works, too. In Othello, trade routes shape the backdrop, with characters like the Moor navigating a world of commerce and power. In Timon of Athens, wealth and betrayal intertwine, as Timon’s generosity to merchant friends leads to his downfall when they abandon him. These examples show Shakespeare’s consistent interest in how bonds shape human behavior, from loyalty to greed.

Themes of Trust and Trade in Merchants Bonding

Trust as the Foundation of Commerce

Trust is the bedrock of merchants bonding in Shakespeare’s plays. In The Merchant of Venice, Antonio’s bond with Shylock hinges on mutual reliance, despite their animosity. Shakespeare shows trust as both fragile and essential, a theme echoed in modern business. For example, today’s supply chain partnerships rely on trust, much like Elizabethan merchants depended on reliable trade networks. As Bassanio says, “I owe the most in money and in love” (Act 1, Scene 1), blending financial and emotional trust.

Risk and Reward in Merchant Bonds

Merchants in Shakespeare’s plays take significant risks. Antonio’s ships are at sea, vulnerable to storms, while Egeon in The Comedy of Errors travels despite trade bans, risking his life. These risks mirror Elizabethan realities, where shipwrecks or piracy could ruin fortunes. Shakespeare contrasts these risks with rewards, like Antonio’s potential profits or Bassanio’s successful courtship. Modern parallels include entrepreneurs investing in startups or crowdfunding, where trust and risk intertwine.

Moral and Ethical Dilemmas

Merchant bonds raise ethical questions in Shakespeare’s works. In The Merchant of Venice, Shylock’s insistence on his bond’s terms sparks debate about justice versus mercy. Is Shylock’s demand fair, or does it reflect greed? Similarly, in Timon of Athens, merchants’ refusal to aid Timon questions loyalty in commerce. Below is a comparison of ethical dilemmas across plays:

| Play | Ethical Dilemma | Key Quote |

|---|---|---|

| The Merchant of Venice | Justice vs. mercy in enforcing bonds | “The quality of mercy is not strained” (Act 4, Scene 1) |

| The Comedy of Errors | Trust vs. misunderstanding in trade | “I am not bound to please thee” (Act 4, Scene 1) |

| Timon of Athens | Loyalty vs. self-interest in wealth | “You mistake my love” (Act 3, Scene 2) |

Historical Context: Merchants Bonding in Elizabethan England

The Economic Landscape of Shakespeare’s Time

Elizabethan England was a hub of trade, with merchants exporting wool and importing spices, silks, and sugar. Venice, a model for Shakespeare’s settings, was a global trade center, with sophisticated credit systems. According to historical records from the Worshipful Company of Merchant Taylors (est. 1327), merchants used bonds to secure loans, often relying on personal reputation. Shakespeare’s plays reflect this, with characters like Antonio navigating complex financial networks. The era’s economic growth, driven by exploration, parallels modern globalization.

Social Dynamics of Merchant Relationships

Merchants built trust through guilds, contracts, and personal ties. In London, merchant guilds enforced codes of conduct, ensuring reliability. Shakespeare captures this in his portrayal of merchants as community figures, like Antonio, whose reputation secures his loans. However, breaches of trust, as with Shylock, could lead to social exclusion. These dynamics highlight the interplay of commerce and community, a theme Shakespeare weaves into his narratives.

Timeline: Key Mercantile Developments (1500–1600)

- 1500s: Rise of London as a trade hub.

- 1565: Establishment of the Royal Exchange, a merchant meeting place.

- 1598: East India Company founded, expanding global trade.

Why Merchants Bonding Resonates Today

Lessons for Modern Business and Relationships

Shakespeare’s merchant bonds offer lessons for today’s professionals. Trust remains critical in business, from contract negotiations to partnerships. For example, Antonio’s bond with Shylock resembles modern peer-to-peer lending platforms, where trust drives investment. Similarly, reputation management in e-commerce echoes Elizabethan merchants’ reliance on social standing. By studying Shakespeare, professionals can learn to navigate trust and risk in their own ventures.

Educational Value for Students and Scholars

For students, analyzing merchants bonding fosters critical thinking. It connects literature to history and economics, encouraging interdisciplinary study. Teachers can use The Merchant of Venice to spark discussions on ethics or trust, while scholars can explore archival trade records to deepen their analysis. A downloadable PDF checklist for analyzing merchant themes is available on our William Shakespeare Insights blog, guiding students through key questions and passages.

Checklist Preview:

- Identify the bond’s terms (financial, social, emotional).

- Analyze how trust shapes character interactions.

- Compare historical and modern parallels.

How to Analyze Merchants Bonding in Shakespeare’s Works

Key Questions to Ask

To study merchants bonding, ask:

- How does the bond drive the play’s conflict?

- What does the bond reveal about trust or betrayal?

- How do economic pressures influence characters’ decisions?

These questions help uncover Shakespeare’s commentary on commerce and human nature.

Tools and Resources for Deeper Study

Explore these resources:

- Folger Shakespeare Library: Offers digital texts and historical context.

- JSTOR: Access scholarly articles on Shakespeare’s economic themes.

- Oxford Shakespeare Editions: Provide annotated plays for close reading.

Try close-reading techniques, like annotating passages about trade or trust, to deepen your analysis. Dr. Emma Smith, Oxford Shakespeare scholar, notes, “Shakespeare’s economic themes reveal the human cost of commerce” (Smith, 2019).

Common Misconceptions About Merchants in Shakespeare

Myth: Merchants Are Solely Greedy

Many assume Shakespeare’s merchants, like Shylock, are driven by greed. However, characters like Antonio show loyalty and sacrifice, risking their lives for friends. Shakespeare portrays merchants as complex, balancing profit with relationships.

Myth: Merchant Bonds Are Purely Financial

While bonds often involve money, they carry emotional weight. Antonio’s bond with Bassanio is rooted in friendship, not just finance. This duality makes Shakespeare’s merchants relatable, reflecting the multifaceted nature of trust.

Infographic: Misconceptions vs. Realities

- Misconception: Merchants are greedy.

- Reality: They balance profit with loyalty (e.g., Antonio’s sacrifice).

- Misconception: Bonds are only financial.

- Reality: Bonds blend money, trust, and emotion (e.g., Bassanio’s debt).

Shakespeare’s portrayal of merchants bonding transcends the Elizabethan stage, offering timeless insights into trust, trade, and human relationships. From Antonio’s risky loan in The Merchant of Venice to Egeon’s perilous journey in The Comedy of Errors, these bonds reveal the delicate balance of economic and emotional stakes. By exploring these themes, readers gain a deeper appreciation for Shakespeare’s commentary on commerce and its moral complexities. Whether you’re a student analyzing The Merchant of Venice, a professional seeking lessons on trust, or a literature enthusiast, these plays invite you to re-read and reflect. Join a discussion group, revisit a play, or explore our William Shakespeare Insights blog for more. What bonds of trust do you see shaping today’s world, and how do they echo Shakespeare’s timeless wisdom?

FAQs

What is the significance of merchants bonding in The Merchant of Venice?

In The Merchant of Venice, merchants bonding drives the plot through Antonio’s loan from Shylock, secured by a “pound of flesh” (Act 1, Scene 3). This bond explores trust, betrayal, and justice, culminating in the trial scene where mercy prevails (Act 4, Scene 1). It reflects Elizabethan commerce while posing universal questions about obligation and humanity.

How does Shakespeare’s portrayal of merchants reflect Elizabethan society?

Shakespeare’s merchants mirror the rising merchant class in Elizabethan England, a time of expanding trade and global exploration. Characters like Antonio embody the era’s reliance on credit and reputation, as seen in historical trade guilds and markets like the Royal Exchange. The plays capture the social and economic dynamics of trust and risk.

Can studying merchants bonding in Shakespeare help modern professionals?

Yes, Shakespeare’s merchant bonds offer lessons for modern business. Trust, as seen in Antonio’s loyalty or Shylock’s contracts, parallels today’s partnerships, contract negotiations, and e-commerce. Professionals can learn to navigate risk, build trust, and address ethical dilemmas, making Shakespeare’s insights relevant to contemporary commerce.

Where can I find more resources on Shakespeare’s economic themes?

Explore the Folger Shakespeare Library for digital texts, JSTOR for scholarly articles, or Oxford’s Shakespeare editions for annotated plays. The William Shakespeare Insights blog also offers guides and checklists for analyzing economic themes, enhancing your study of merchants bonding.