“Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more; Or close the wall up with our English dead!”

These electrifying words, delivered by King Henry V on the fields of Harfleur, have echoed through centuries as one of William Shakespeare’s most stirring calls to courage. Yet behind this iconic moment stands not just a heroic monarch, but a richly woven tapestry of characters in Henry V who bring the play’s profound themes to life: leadership, honor, national identity, the cost of war, and the complex humanity of both victors and vanquished.

Written around 1599 as the triumphant conclusion to Shakespeare’s second tetralogy (following Richard II, Henry IV Part 1, and Henry IV Part 2), Henry V transforms the wild Prince Hal into England’s legendary warrior-king. Understanding the full range of characters in Henry V is essential for any reader, student, or theater enthusiast seeking to grasp how Shakespeare explores the moral ambiguities of power and patriotism. This comprehensive guide offers a complete character list, in-depth analysis of major and minor figures, historical context, thematic connections, and insights from notable performances—far surpassing standard summaries to provide the definitive resource on Shakespeare’s dramatic portrait of Agincourt and its people.

Historical and Dramatic Context

Shakespeare drew heavily from Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles (1577 and 1587 editions) and the anonymous play The Famous Victories of Henry the Fifth for his source material. While grounded in the historical Henry V’s victorious 1415 campaign—culminating in the Battle of Agincourt—Shakespeare took significant dramatic liberties. The real Henry was a disciplined, pious ruler from youth; Shakespeare’s version completes a remarkable arc from the reckless Prince Hal who caroused with Falstaff.

The play blends genres: it is officially a history play, yet incorporates epic elements through the Chorus, comedic interludes with lowborn soldiers, and a romantic courtship finale. Performed originally at the Globe Theatre, Henry V was likely shaped by contemporary Elizabethan patriotism, especially during the threat of the Spanish Armada’s aftermath and England’s campaigns in Ireland.

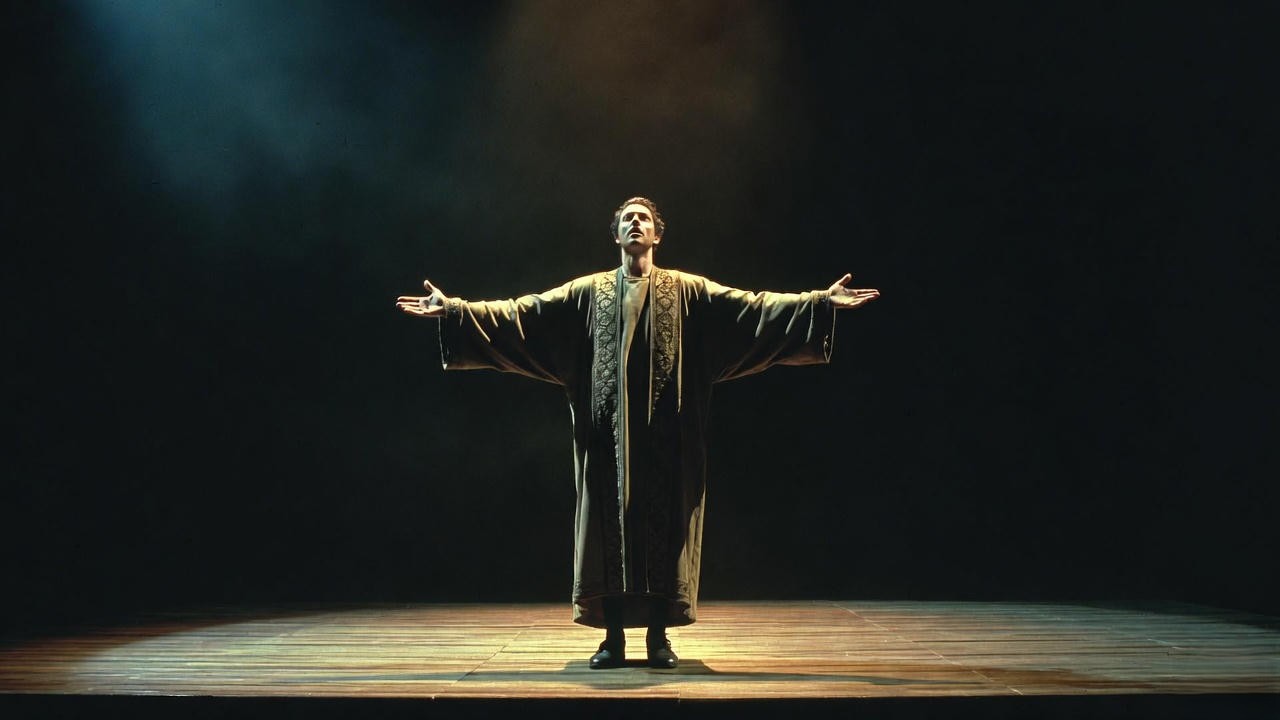

Notable productions have interpreted the play in vastly different lights. Laurence Olivier’s 1944 film, made during World War II, presented an unequivocally heroic Henry to boost morale. Kenneth Branagh’s 1989 adaptation, by contrast, emphasized the mud, blood, and moral cost of war. Tom Hiddleston’s portrayal in the 2012 BBC The Hollow Crown series highlighted Henry’s introspective burden of kingship. These varying interpretations underscore how the characters in Henry V remain open to endless reinterpretation.

Complete List of Characters in Henry V

Shakespeare’s dramatis personae for Henry V is expansive, reflecting the epic scope of a national campaign. Below is a comprehensive, grouped list with allegiance, key traits, and primary appearances (based on the First Folio and modern editions such as the Folger Shakespeare Library).

English Court and Army

- King Henry the Fifth: Protagonist; charismatic, ruthless, eloquent leader (appears throughout).

- Chorus: Narrator who frames the action and apologizes for the stage’s limitations (Prologue, each act).

- Duke of Gloucester and Duke of Bedford: Henry’s loyal brothers (minor roles in council and battle).

- Duke of Exeter: Henry’s uncle; trusted ambassador and warrior (key in Acts II and IV).

- Duke of York: Historical figure seeking atonement; leads charge at Agincourt (Act IV).

- Earl of Salisbury, Westmoreland, Warwick: Noble supporters (brief appearances).

- Archbishop of Canterbury and Bishop of Ely: Church leaders justifying the war (Act I, Scene 1–2).

- Captain Fluellen: Welsh officer; pedantic, honorable, comic (Acts III–V).

- Captain Gower: English officer; Fluellen’s friend (Acts III–IV).

- Captain Jamy: Scottish officer (Act III, Scene 2).

- Captain Macmorris: Irish officer (Act III, Scene 2).

- Pistol: Boastful, cowardly soldier; former tavern companion (Acts II–V).

- Bardolph: Thief and follower of Pistol (executed in Act III).

- Nym: Cowardly soldier (Acts II–III).

- Boy: Former page to Falstaff; insightful commentator (Acts II–IV).

- Mistress Quickly (Hostess): Pistol’s wife; reports Falstaff’s death (Act II, Scene 1 and 3).

French Court and Army

- King Charles VI: Aging, cautious French king.

- Queen Isabel: His wife; appears in final peace negotiations.

- Lewis the Dauphin (Prince): Arrogant heir; mocks Henry with tennis balls.

- Princess Katherine (Catherine): Charles’s daughter; Henry’s eventual bride.

- Alice: Katherine’s lady-in-waiting.

- Constable of France: Proud military leader.

- Duke of Burgundy: Mediator in peace talks (Act V).

- Montjoy: French herald; delivers challenges and concessions.

- Various French lords: Orléans, Rambures, Bourbon, Grandpré, etc.

Other Minor Figures

- Sir Thomas Erpingham: Elderly English knight.

- Bates, Court, Williams: Common English soldiers who debate with disguised Henry.

- French Messenger, Governors, Ambassadors, etc.

In total, the play features approximately 50 named parts—many doubled in original productions—illustrating the vast social spectrum Shakespeare examines.

In-Depth Analysis of Major Characters

King Henry V

At the heart of the play stands Henry himself, one of Shakespeare’s most debated protagonists. His transformation from the prodigal Hal of the Henry IV plays into a model Renaissance prince is complete by the opening scene, where Canterbury marvels: “The courses of his youth promised it not.”

Henry displays extraordinary rhetorical skill—witness the soaring St. Crispin’s Day speech (“We few, we happy few, we band of brothers”) that turns numerical disadvantage into immortal glory. Yet Shakespeare complicates this heroism. Henry orders the execution of Bardolph for theft and threatens Harfleur with rape and slaughter if it does not surrender. His disguised nighttime conversation with soldiers Williams and Bates reveals private doubts about the king’s responsibility for his subjects’ souls.

Critics remain divided: Harold Bloom views Henry as Shakespeare’s ideal ruler, while Stephen Greenblatt argues he exemplifies Machiavellian pragmatism. Historically, the real Henry V was devout and militarily brilliant but also capable of harsh retribution (e.g., ordering prisoners killed at Agincourt when fearing a French counterattack—a detail Shakespeare includes). Modern productions often highlight this duality: Branagh’s Henry weeps over the dead; Hiddleston’s appears haunted by power’s weight.

Chorus

Unique among Shakespeare’s plays, Henry V employs a single Chorus who speaks directly to the audience in soaring verse. The famous opening—“O for a Muse of fire, that would ascend / The brightest heaven of invention”—acknowledges the theater’s limitations while inviting imagination to “piece out our imperfections with your thoughts.”

The Chorus serves multiple functions: bridging scene changes, providing epic narration, and shaping patriotic sentiment. Notably, the Epilogue reminds audiences of Henry’s short reign and the eventual loss of France—tempering triumphalism. Scholars such as Patricia Parker note how the Chorus creates dramatic irony, promising grandeur the stage cannot fully deliver.

Fluellen, Gower, Macmorris, and Jamy

The four captains represent the united kingdoms under Henry’s banner: England (Gower), Wales (Fluellen), Scotland (Jamy), and Ireland (Macmorris). Their Act III, Scene 2 exchange—filled with comic accents and national stereotypes—offers light relief amid battle preparations.

Fluellen emerges as the most developed, a pedantic scholar-soldier obsessed with “the disciplines of the pristine wars of the Romans.” His forced eating of the leek by Pistol in Act V provides comic closure while affirming honor across rank. The scene subtly comments on British unity, relevant to Elizabethan concerns over incorporating Wales, Scotland, and Ireland.

Pistol, Bardolph, Nym, and Mistress Quickly

These Eastcheap survivors link Henry V to the Henry IV plays, contrasting tavern lowlife with royal politics. Pistol’s bombastic language parodies heroic rhetoric (“Let floods o’erswell, and let the world be drowned!”), exposing cowardice beneath bravado.

Bardolph’s execution for stealing a pax (a church tablet) marks Henry’s rejection of former companions and his commitment to martial justice. The Boy’s moral commentary—“I did never know so full a voice issue from so empty a heart”—underscores Shakespeare’s critique of false honor. Mistress Quickly’s moving, malapropism-filled account of Falstaff’s death (“a’ parted ev’n just between twelve and one… for his nose was as sharp as a pen, and a’ babbled of green fields”) provides poignant closure to that legendary relationship.

Princess Katherine and Alice

Princess Katherine (often spelled Catherine in historical contexts) humanizes the French side, transforming the enemy from abstract foes into individuals with vulnerability and charm. Her famous English lesson scene (Act III, Scene 4)—conducted entirely in French with Alice as her attendant—serves multiple dramatic purposes. The comic misunderstanding of English words (“de foot et de coun”) underscores language barriers while subtly eroticizing courtship.

Katherine’s final wooing by Henry in Act V reveals a politically astute woman who navigates power dynamics with quiet dignity. Though she declares “Is it possible dat I sould love de enemy of France?” her acceptance of Henry seals the peace treaty. Modern feminist critics, such as Jean E. Howard, argue that Katherine embodies the female cost of war—reduced to a diplomatic prize—while others praise Shakespeare for granting her agency through wit and silence.

Historically, Catherine of Valois did marry Henry V in 1420, bore Henry VI, and later secretly wed Owen Tudor, founding the Tudor dynasty. Shakespeare compresses and romanticizes this alliance.

The French King, Dauphin, and Constable

The French court provides a foil to Henry’s disciplined leadership through arrogance and disunity. King Charles VI appears cautious and weakened, haunted by his real-life mental illness (though Shakespeare downplays this). The Constable of France embodies traditional chivalric pride, boasting before Agincourt only to lament “O diable!” as defeat looms.

The Dauphin (Lewis) is the most vividly drawn antagonist, mocking Henry with the infamous tennis balls gift (Act I, Scene 2)—a dramatic invention symbolizing youthful disdain. His bravado crumbles on the battlefield; Shakespeare denies him presence at Agincourt (unlike history) to heighten French humiliation. These portrayals reflect Elizabethan stereotypes of French vanity while serving dramatic contrast to English resolve.

Minor Characters and Their Significance

Though less spotlighted, minor characters in Henry V amplify the play’s thematic depth and social breadth.

The Archbishop of Canterbury and Bishop of Ely open the play with the lengthy Salic law exposition (Act I, Scene 2), justifying Henry’s French claim. Critics often view this as satirical: the church funds the war to divert Henry from seizing ecclesiastical lands, exposing political expediency behind pious rhetoric.

Henry’s uncles and supporters—Exeter, Bedford, Gloucester, and the Duke of York—form a loyal inner circle, contrasting the fractious French nobility. York’s poignant request to lead the vanguard at Agincourt and his subsequent death add pathos.

The common soldiers John Bates, Alexander Court, and Michael Williams provide the play’s moral core in the disguised king scene (Act IV, Scene 1). Williams’s challenge—“But if the cause be not good, the king himself hath a heavy reckoning to make”—forces Henry to confront the human cost of ambition. This exchange, unique in the history plays, democratizes ethical debate.

Montjoy the French herald recurs as a dignified intermediary, his repeated concessions tracing French decline. Sir Thomas Erpingham, the elderly knight who lends Henry his cloak for disguise, symbolizes experienced loyalty.

Even fleeting figures like the Boy (former page to Falstaff) offer sharp commentary, condemning Pistol’s crew and lamenting Bardolph and Nym’s executions before his own offstage death while guarding luggage.

Collectively, these minor roles illustrate class stratification, the universality of fear in war, and the gap between royal justification and soldierly reality.

Character Relationships and Thematic Connections

Shakespeare masterfully interweaves relationships to explore core themes.

Henry’s decisive break with his Eastcheap past—symbolized by Falstaff’s offstage death reported by Mistress Quickly—marks his maturation into kingship. Yet echoes linger: Pistol’s bombast parodies heroic language, reminding audiences of Hal’s former world.

Parallel structures between English and French courts highlight national character. Both have proud nobles and cautious monarchs, suggesting shared humanity beneath rivalry. The four captains’ banter celebrates (and gently mocks) British multiplicity, reflecting James I’s later “Union of Crowns” aspirations.

Language itself becomes a character: Katherine’s scene and the soldiers’ dialects underscore identity and communication. Honor spans classes—from Fluellen’s scholarly code to Williams’s blunt integrity—while justice proves uneven (Bardolph hanged for theft, nobles spared).

Ultimately, every relationship orbits Henry, testing his claim to exemplary rule.

Characters in Performance and Adaptation

Interpretations of Henry V’s characters shift with cultural context.

Laurence Olivier’s 1944 film presented a radiant, unambiguous hero amid WWII propaganda needs, cutting subversive elements like the traitors’ execution and bishops’ cynicism. Kenneth Branagh’s 1989 version restored grit: his mud-soaked Henry delivers St. Crispin’s Day through tears, emphasizing war’s toll. The disguised scene becomes anguished soul-searching.

Tom Hiddleston’s 2012 Hollow Crown portrayal leaned introspective, a thoughtful king burdened by inherited violence. Stage productions often experiment: the RSC’s 2015 version cast women in soldier roles, while anti-war readings (post-Vietnam or Iraq) foreground Henry’s threats and prisoner executions.

Pistol and the comic subplot frequently provide directorial choices—broad farce or tragic underbelly. Fluellen’s Welshness has evolved from stereotype to celebration of diversity. Katherine’s role grows in modern productions emphasizing gender dynamics.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who is the main protagonist in Henry V? King Henry V is the clear protagonist, tracing his journey from new monarch to triumphant (yet morally complex) conqueror.

How many characters are there in Henry V? Approximately 50 named characters, though many minor roles were doubled in original Globe productions.

Is Falstaff in Henry V? No, Sir John Falstaff does not appear onstage. His death is reported by Mistress Quickly in Act II, Scene 3, providing emotional closure to the Henry IV storyline.

Who is the comic relief in Henry V? Primary comic relief comes from Pistol, Bardolph, Nym, and Fluellen—whose pedantic honor and national stereotypes balance the play’s epic tone.

What is the role of the Chorus in Henry V? The Chorus acts as narrator, framing each act, apologizing for theatrical limitations, and urging the audience’s imagination to supply epic spectacle.

How does Shakespeare portray the French characters? French characters are often arrogant and overconfident early on (especially the Dauphin), but humanized through defeat and Katherine’s charm—serving both dramatic contrast and subtle critique of stereotyping.

The characters in Henry V form one of Shakespeare’s richest ensembles, spanning kings and commoners, victors and vanquished, comic braggarts and quiet heroes. Together they illuminate timeless questions: What justifies war? What defines true honor? How does power shape (and misshape) humanity?

From Henry’s magnetic yet troubling leadership to the Chorus’s poetic framing, from Fluellen’s leek to Katherine’s fractured English, each figure contributes to a portrait far more nuanced than mere patriotic triumph. Whether read as celebration or cautionary tale, Henry V endures because its characters remain vividly, painfully human.

Revisit the play, watch a production—Olivier for inspiration, Branagh for grit, or a fresh stage interpretation—and decide for yourself which character speaks most urgently today. Who is your favorite figure in Shakespeare’s Agincourt gallery? Share in the comments below.