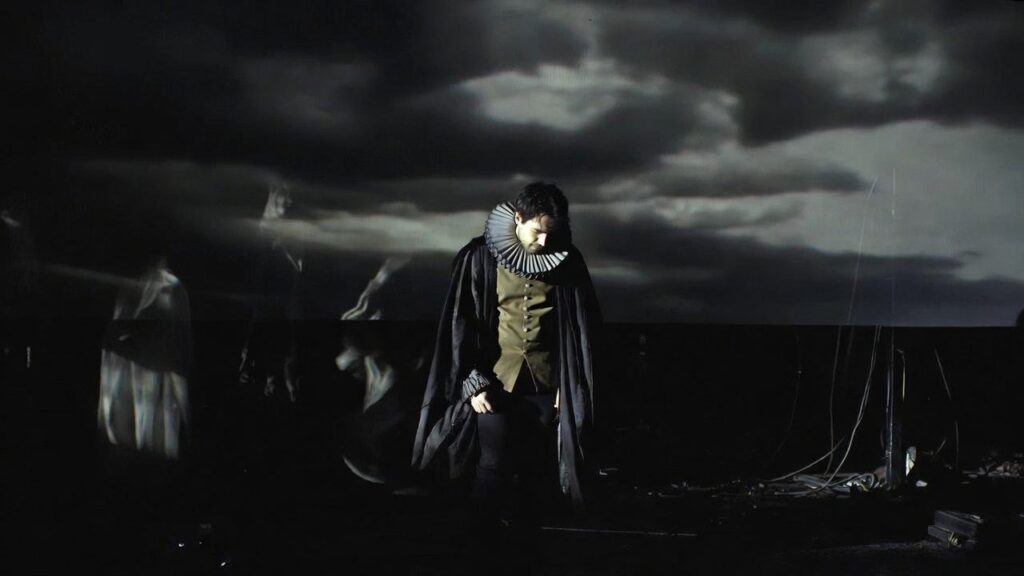

Imagine a prince standing alone on a cold Danish stage, his mind a whirlwind of grief, rage, and existential dread. He speaks not to the other characters, but directly to us—the audience—unveiling thoughts too dangerous or intimate for anyone else to hear. These are Hamlet’s soliloquies, the beating heart of Shakespeare’s greatest tragedy. In Hamlet soliloquies, we find the prince’s raw psyche laid bare: his suicidal despair, his paralyzing indecision, his philosophical wrestling with life and death, and ultimately, his shift toward bloody resolve. These seven key speeches do more than reveal Hamlet’s inner world—they propel the entire plot forward, turning personal torment into catastrophic action.

For students grappling with essays, teachers seeking deeper classroom insights, or literature lovers wanting to truly understand why Hamlet endures as the pinnacle of introspective drama, this comprehensive guide offers everything you need. We’ll examine each of the seven major soliloquies chronologically, with original excerpts, modern paraphrases, line-by-line breakdowns, psychological revelations, and their direct impact on the tragedy’s unfolding. Drawing from the Folio and Quarto texts, scholarly consensus, and performance traditions, this article goes beyond surface summaries to provide skyscraper-level depth—more thorough, insightful, and actionable than fragmented blog posts or basic study guides.

Why Soliloquies Matter in Hamlet

A soliloquy is a dramatic device where a character speaks their thoughts aloud while alone (or believing themselves to be), allowing the audience privileged access to their mind. In most Elizabethan plays, soliloquies serve exposition or moral commentary, but Shakespeare elevates them in Hamlet to unprecedented psychological realism. Hamlet delivers more soliloquies than any other Shakespearean protagonist—seven major ones—creating an intimate, almost voyeuristic bond with the viewer.

These speeches showcase Shakespeare’s mastery of language: rich metaphors of disease and decay, iambic pentameter that mirrors racing thoughts, and rhetorical questions that echo universal human struggles. They trace Hamlet’s evolution from paralyzing grief to decisive (if doomed) action, while advancing core themes—revenge ethics, appearance vs. reality, corruption in the state, and the human condition. Scholars widely agree on these seven as the pivotal ones, each building on the last to map the prince’s tragic arc.

The 7 Key Soliloquies: In-Depth Analysis

1. First Soliloquy: “O, that this too too solid flesh would melt” (Act 1, Scene 2)

Context Fresh from his father’s funeral and his mother’s hasty remarriage to Claudius, Hamlet is left alone as the court exits. The scene exposes the “rotten” state of Denmark through personal betrayal.

Key Excerpts and Modern Paraphrase “O, that this too too solid flesh would melt, / Thaw and resolve itself into a dew! / Or that the Everlasting had not fix’d / His canon ‘gainst self-slaughter! O God! God!” (1.2.129–132)

Modern: Oh, if only my body could just dissolve into nothing! Or if God hadn’t forbidden suicide! How weary, stale, flat, and pointless the world seems to me!

Line-by-Line Breakdown Hamlet wishes for annihilation rather than endure the “unweeded garden” of corruption. He contrasts his father (“Hyperion”) with Claudius (“a satyr”), and condemns Gertrude’s “incestuous sheets.” The speech ends in frustrated silence: “But break, my heart, for I must hold my tongue.”

What It Reveals About Hamlet Profound grief mixed with suicidal ideation, misogynistic disgust toward his mother, and a sense of universal decay. This establishes his baseline despair and intellectual sensitivity.

How It Drives the Tragedy It sets the tone of moral corruption and foreshadows Hamlet’s inaction rooted in overwhelming emotion.

2. Second Soliloquy: “O all you host of heaven! O earth! what else?” (Act 1, Scene 5)

Context Right after the Ghost reveals Claudius murdered King Hamlet and demands revenge.

Key Excerpts and Modern Paraphrase “Remember thee? / Ay, thou poor ghost, whiles memory holds a seat / In this distracted globe.” (1.5.95–97)

Modern: Remember you? Yes, poor ghost—as long as I have memory, I’ll remember. I’ll wipe my mind clean of everything else and focus only on your command.

Line-by-Line Breakdown Hamlet vows vengeance, curses his mother and uncle, and plans his “antic disposition” (feigned madness).

What It Reveals Shock turning to furious determination; the birth of his revenge mission and deceptive strategy.

Plot Impact This ignites the central revenge plot, creating suspense around whether Hamlet will act.

3. Third Soliloquy: “O, what a rogue and peasant slave am I!” (Act 2, Scene 2)

Context After watching the players perform a passionate speech about Hecuba, Hamlet berates himself for inaction.

Key Excerpts and Modern Paraphrase “O, what a rogue and peasant slave am I! / Is it not monstrous that this player here, / But in a fiction, in a dream of passion…” (2.2.550–552)

Modern: What a worthless coward I am! This actor can fake such emotion over nothing, while I do nothing about my real cause.

Line-by-Line Breakdown He envies the player’s tears and vows to use the play to “catch the conscience of the king.”

What It Reveals Self-loathing over procrastination; intellect as both gift and curse.

Plot Impact Directly leads to “The Mousetrap” play, confirming Claudius’s guilt.

4. Fourth Soliloquy: “To be, or not to be” (Act 3, Scene 1) – The Most Famous

Context Hamlet contemplates existence before Ophelia enters (debated if true soliloquy, but traditionally treated as one).

Key Excerpts and Modern Paraphrase “To be, or not to be—that is the question: / Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer / The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune…” (3.1.56–58)

Modern: To live or to die—that’s the question. Is it better to endure life’s sufferings or end them by dying? But who knows what comes after death?

Line-by-Line Breakdown He weighs endurance against suicide, fearing the “undiscovered country” of afterlife; “conscience does make cowards of us all.”

What It Reveals Existential crisis, fear of the unknown, philosophical depth on suffering and action.

Why It’s Iconic Its universal appeal to mortality and mental anguish; endlessly quoted in culture, psychology, and philosophy.

5. Fifth Soliloquy: “‘Tis now the very witching time of night” (Act 3, Scene 2)

Context The play-within-a-play (“The Mousetrap”) has just confirmed Claudius’s guilt. Hamlet, electrified by success, prepares to confront his mother in her closet while warning himself against excessive violence.

Key Excerpts and Modern Paraphrase “’Tis now the very witching time of night, / When churchyards yawn and hell itself breathes out / Contagion to this world.” (3.2.378–380)

Modern: It’s the witching hour—when graves open and evil spreads. Now I could drink hot blood and do such bitter business the day would tremble to see it. But I’ll speak daggers to my mother, yet use none.

Line-by-Line Breakdown The speech opens with gothic imagery of midnight horror, showing Hamlet embracing a darker, more vengeful persona. He consciously sets limits: verbal cruelty is permitted, physical murder of Gertrude is not. This self-imposed moral boundary reveals both his growing ruthlessness and his lingering conscience.

What It Reveals About Hamlet A pivotal shift. Earlier soliloquies were dominated by paralysis and self-doubt; here we see purposeful energy and a willingness to channel his rage. Yet the restraint (“use none”) underscores his complex morality—he is not a cold-blooded killer.

Plot Impact This directly leads to the closet scene (Act 3, Scene 4), where Hamlet accidentally kills Polonius, thinking him to be Claudius behind the arras. That murder spirals the tragedy into irreversible chaos: Ophelia’s madness, Laertes’s revenge plot, and Hamlet’s exile.

6. Sixth Soliloquy: “Now might I do it pat” (Act 3, Scene 3)

Context Hamlet finds Claudius alone, apparently praying. This is the perfect, unguarded moment for revenge—yet Hamlet hesitates.

Key Excerpts and Modern Paraphrase “Now might I do it pat, now he is praying, / And now I’ll do’t. And so he goes to heaven, / And so am I revenged.” (3.3.73–75)

Modern: Right now I could kill him easily—he’s praying. But if I kill him while he’s repenting, his soul goes to heaven. That would be revenge for my father, but a reward for him. No.

Line-by-Line Breakdown Hamlet reasons that killing Claudius at prayer would send the king to salvation, defeating the purpose of revenge (which demands Claudius suffer in the afterlife as his father did in purgatory). He decides to wait for a moment of sin.

What It Reveals The tragic core of Hamlet’s character: over-intellectualization and moral scrupulosity as fatal flaws. He is not indecisive from cowardice alone, but from an acute ethical awareness that paralyzes action.

Plot Impact By sparing Claudius here, Hamlet allows the king to survive and later orchestrate the deadly duel plot. This moment of hesitation is widely regarded by scholars as the turning point that seals the tragedy’s body count.

7. Seventh Soliloquy: “How all occasions do inform against me” (Act 4, Scene 4)

Context Hamlet watches Fortinbras’s army march to fight for a worthless patch of land. The sight shames him into final resolution.

Key Excerpts and Modern Paraphrase “How all occasions do inform against me / And spur my dull revenge!” (4.4.32–33)

“How stand I then, / That have a father kill’d, a mother stain’d, / Excitements of my reason and my blood, / And let all sleep…” (4.4.56–59)

Modern: Everything around me accuses me of inaction and prods my dull revenge. I have a murdered father, a dishonored mother, and powerful reasons to act—yet I do nothing. Even this young Fortinbras risks everything for almost nothing. From now on, my thoughts will be bloody or they will be worth nothing.

Line-by-Line Breakdown Hamlet contrasts his own inaction with Fortinbras’s decisive (if arguably pointless) military ambition. The speech ends with a vow: “My thoughts be bloody, or be nothing worth!”

What It Reveals A decisive psychological turning point. Hamlet moves from contemplation to commitment. While earlier speeches questioned existence and morality, this one embraces action—even if it arrives too late.

Plot Impact This soliloquy marks the beginning of the endgame. Hamlet returns to Denmark with lethal intent, setting the stage for the final bloodbath in Act 5.

How the Soliloquies Track Hamlet’s Psychological Evolution

These seven speeches form a clear arc:

- Despair & Grief (1st) → suicidal ideation and disgust at the world

- Rage & Vow (2nd) → revenge is born

- Self-Loathing & Paralysis (3rd) → guilt over inaction

- Existential Crisis (4th) → philosophical questioning of life itself

- Dark Resolve (5th) → willingness to embrace cruelty (with limits)

- Moral Hesitation (6th) → overthinking prevents action

- Final Determination (7th) → shame propels him toward violence

This progression is not linear growth but tragic oscillation: intellect and conscience repeatedly sabotage instinct, prolonging suffering and multiplying deaths.

| Soliloquy | Dominant Emotion | Key Theme | Resulting Action/Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Despair | Corruption & decay | Establishes baseline melancholy |

| 2 | Rage | Revenge duty | Launches central conflict |

| 3 | Self-disgust | Inaction vs. passion | Triggers play-within-play |

| 4 | Existential doubt | Life vs. death | Deepens audience empathy |

| 5 | Dark purpose | Controlled cruelty | Leads to Polonius’s death |

| 6 | Moral scruple | Ethics of revenge | Delays killing, escalates tragedy |

| 7 | Shame → Resolve | Action vs. thought | Commits to bloody endgame |

Broader Themes and Literary Significance

Hamlet’s soliloquies are not mere character moments—they are engines of tragedy. His prolonged indecision allows poison (literal and metaphorical) to spread: Ophelia’s madness, Gertrude’s guilt, Laertes’s vengeance, and the final slaughter.

Shakespeare uses these speeches to explore:

- Appearance vs. Reality — feigned madness vs. genuine torment

- Corruption & Mortality — “something is rotten in the state of Denmark”

- Revenge Ethics — Is vengeance ever just? Does it corrupt the avenger?

- The Human Condition — suffering, doubt, the fear of the unknown afterlife

The language itself is revolutionary: dense metaphors (disease, weeds, warfare), questions that invite reflection, and rhythms that mimic thought patterns. These elements have made the soliloquies foundational texts in literature, psychology, philosophy, and theater.

Expert Insights and Common Misconceptions

- Is “To be, or not to be” a true soliloquy? Traditionally yes, though some scholars note Ophelia’s presence makes it an “overheard meditation.” Performance tradition treats it as solitary introspection.

- Folio vs. Quarto variations — The First Folio (1623) is generally considered more authoritative for these speeches, though the Second Quarto (1604–5) offers richer textual detail in places.

- Modern psychological readings — Many clinicians see Hamlet exhibiting symptoms consistent with major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety, and obsessive rumination—yet he retains insight and wit, complicating simple diagnoses.

Why These Soliloquies Endure

Hamlet’s seven key soliloquies remain unmatched in Western literature for their psychological depth, philosophical range, and dramatic power. They do not merely reveal the prince’s mind—they expose the universal struggle between thought and action, morality and impulse, life and death. By tracing his journey from suicidal despair to bloody determination, we understand why the tragedy feels so personal and so inevitable.

Revisit Hamlet with these speeches as your guide: read them aloud, watch different performances, and notice how each one shifts the emotional temperature of the play. They are not museum pieces—they are living, breathing portraits of a mind at war with itself.

FAQs

How many soliloquies does Hamlet actually have? Seven major ones are universally recognized by scholars and editors, though shorter asides and semi-solitary speeches exist. These seven are the most substantial and plot-defining.

What is the most famous Hamlet soliloquy? “To be, or not to be” (Act 3, Scene 1) — it has become a cultural shorthand for existential questioning.

Do the soliloquies prove Hamlet is mad? No. They reveal intense grief, philosophical depth, and feigned madness (“antic disposition”), but his speeches show coherent, self-aware thought—often more lucid than anyone else in the play.

How have these soliloquies influenced modern literature and psychology? They inspired existentialist thinkers (Camus, Sartre), shaped modern depictions of depression and indecision, and appear in countless adaptations from film to therapy discussions.