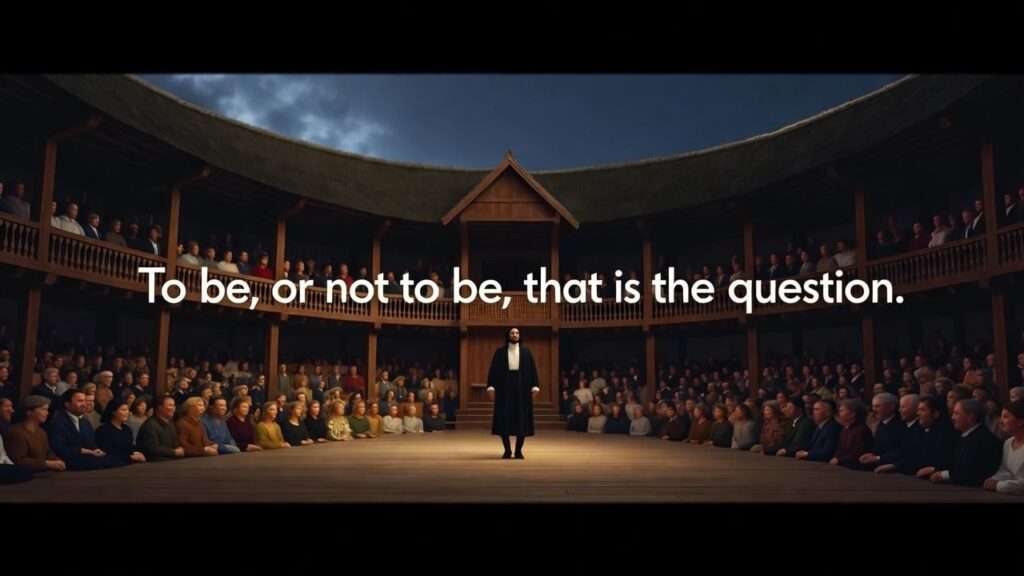

Picture yourself in the dimly lit Globe Theatre, 1601, as the tormented Prince of Denmark steps forward, his voice cutting through the hushed crowd: “To be, or not to be, that is the question.” These famous lines of Hamlet, penned by William Shakespeare, have echoed through centuries, captivating audiences with their raw emotion and philosophical depth. Why do these words still resonate? Whether you’re a student grappling with Shakespeare’s language, a theater enthusiast, or simply curious about Hamlet’s enduring wisdom, this article unveils the meaning, context, and cultural impact of Hamlet’s most iconic quotes. Backed by Shakespearean scholarship and enriched with practical insights, we’ll explore how these lines illuminate the human condition and inspire reflection today.

Why Hamlet’s Lines Endure: The Power of Shakespeare’s Words

The Universal Appeal of Hamlet

Hamlet is more than a play; it’s a mirror reflecting humanity’s deepest struggles. Themes of mortality, indecision, madness, and morality weave through its narrative, making it a timeless masterpiece. From Elizabethan playhouses to modern Broadway stages, Hamlet’s universal appeal lies in its exploration of questions we all face: What is the meaning of life? How do we confront death? Its global reach is evident in countless adaptations—Japanese Noh theater, Bollywood films, and even Disney’s The Lion King. These stories resonate because Hamlet’s dilemmas are our own, transcending time and culture.

Shakespeare’s Mastery of Language

Shakespeare’s genius lies in his ability to craft language that is both poetic and profound. Hamlet’s famous lines, often delivered in iambic pentameter, mimic the natural rhythm of speech while packing emotional and intellectual weight. His use of metaphors, paradoxes, and rhetorical flourishes—like Hamlet’s introspective soliloquies—creates unforgettable dialogue. For instance, the phrase “to be, or not to be” isn’t just a question; it’s a rhythmic meditation on existence. Elizabethan audiences, familiar with the cadence of poetry, would have felt its pulse. As scholar Harold Bloom notes, “Shakespeare’s language in Hamlet is a universe unto itself, where every word carries the weight of human thought.”

The Cultural Impact of Hamlet’s Lines

Hamlet’s quotes have seeped into the fabric of modern culture. Phrases like “something is rotten” or “the lady doth protest too much” are used in political discourse, literature, and even casual conversation. Films like Star Wars echo Hamlet’s existential angst, while TV shows like Breaking Bad draw on its moral complexities. These lines are not just literary relics; they’re tools for understanding our world, from personal struggles to societal corruption. Their adaptability ensures they remain relevant, whether in a classroom or a Netflix series.

The Most Famous Lines of Hamlet: A Deep Dive

“To be, or not to be, that is the question”

Context: In Act 3, Scene 1, Hamlet delivers his most famous soliloquy, wrestling with the choice between life and death. Alone on stage, he ponders whether to endure suffering or end it through suicide, a question sparked by his father’s murder and his mother’s hasty remarriage.

Meaning: This line encapsulates an existential crisis. “To be” represents life, with its pain and uncertainty; “not to be” suggests death, an unknown that might bring peace or torment. The soliloquy explores fear of the afterlife (“the undiscovered country”), indecision, and the human condition. It’s a philosophical cornerstone, questioning the value of existence itself.

Impact: Beyond literature, this line has shaped philosophy, psychology, and popular culture. It’s quoted in therapy sessions, referenced in films like Schindler’s List, and even parodied in memes. Its brevity and depth make it a universal touchstone for grappling with life’s big questions.

Example: Consider its use in modern contexts—a motivational speaker might invoke it to inspire action, or a therapist might use it to spark discussion about mental health. Its versatility is its power.

“Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him, Horatio”

Context: In Act 5, Scene 1, Hamlet holds the skull of Yorick, the court jester, in the graveyard. This moment, known as the “gravedigger scene,” occurs as Hamlet confronts mortality head-on, surrounded by death’s stark reality.

Meaning: The line is a poignant reflection on mortality. Yorick, once a lively figure, is now a lifeless skull, reminding Hamlet—and us—that death levels all. The phrase “memento mori” (remember you must die) resonates here, urging humility and introspection. Hamlet’s nostalgia for Yorick contrasts with the grim reality of decay.

Impact: This scene has inspired countless artistic depictions, from paintings to modern theater. It’s a reminder of life’s transience, influencing works like T.S. Eliot’s poetry and Ingmar Bergman’s films. Scholar Stephen Greenblatt notes that this moment’s staging in Elizabethan theaters, with real skulls often used, would have chilled audiences.

Expert Insight: The line’s power lies in its intimacy—Hamlet’s personal connection to Yorick makes death feel immediate, not abstract.

“The lady doth protest too much, methinks”

Context: In Act 3, Scene 2, Queen Gertrude comments on a player’s exaggerated performance during the play-within-a-play, designed by Hamlet to expose Claudius’s guilt. The line subtly critiques hypocrisy.

Meaning: Gertrude’s observation suggests that excessive protestations often hide truth. In the play, it hints at her own denial of complicity in King Hamlet’s death. The phrase has evolved into a modern idiom for spotting insincerity or overcompensation.

Impact: Today, it’s used to call out exaggerated denials in politics, media, or personal interactions. For example, a politician’s fervent denial of scandal might prompt this quote in commentary. Its sharp wit makes it a favorite for critiquing human behavior.

Example: In a recent news cycle, a public figure’s repeated claims of innocence were dubbed “protesting too much” by analysts, showing the line’s enduring relevance.

“Something is rotten in the state of Denmark”

Context: Spoken by Marcellus in Act 1, Scene 4, this line follows the Ghost’s appearance, signaling corruption at Elsinore’s core. It foreshadows the moral and political decay Hamlet uncovers.

Meaning: The phrase captures a sense of unease, suggesting that the kingdom’s troubles stem from deeper, systemic issues—namely, Claudius’s usurpation and murder. It’s a metaphor for societal or institutional rot.

Impact: This quote is often invoked in discussions of corruption, from corporate scandals to political upheavals. Its broad applicability makes it a staple in editorials and speeches, resonating with audiences aware of systemic flaws.

“Get thee to a nunnery”

Context: In Act 3, Scene 1, Hamlet berates Ophelia, urging her to retreat to a convent. This outburst follows his “To be, or not to be” soliloquy, reflecting his turmoil and distrust.

Meaning: Interpretations vary: Is Hamlet protecting Ophelia from a corrupt world, or is he cruelly rejecting her? The term “nunnery” may also imply a brothel in Elizabethan slang, adding ambiguity. The line raises questions about gender dynamics and Hamlet’s mental state.

Impact: Feminist critics have scrutinized this line, noting its harshness toward Ophelia. Modern productions often use it to explore themes of misogyny or mental instability. Its complexity invites debate, making it a focal point in academic discussions.

Tip: Readers approaching this line should consider both its historical context and modern gender perspectives to fully grasp its nuances.

Historical and Theatrical Context of Hamlet’s Lines

Elizabethan Theater and Audience Reception

In Shakespeare’s time, the Globe Theatre was a bustling hub where diverse audiences—nobles, merchants, and groundlings—gathered. Hamlet’s soliloquies, delivered directly to the crowd, broke the fourth wall, creating intimacy. Actors used minimal props, relying on language to paint vivid scenes. As scholar Emma Smith notes in her book This Is Shakespeare, the play’s raw emotional power captivated Elizabethan audiences, who saw their own fears and ambitions in Hamlet’s words. Primary accounts, like those from diarist John Manningham, describe the play’s immediate impact in 1601.

Hamlet’s Evolution Through the Ages

Hamlet’s lines have been reinterpreted across centuries. In the Romantic era, actors like Edmund Kean emphasized Hamlet’s emotional intensity, while modern productions, like Benedict Cumberbatch’s 2015 performance, highlight psychological realism. Kenneth Branagh’s 1996 film adaptation brought cinematic grandeur, with “To be, or not to be” set against a stark, snowy backdrop. A comparison table of performances (e.g., David Tennant’s introspective delivery vs. Laurence Olivier’s dramatic flair) shows how directors shape these lines to reflect their era’s sensibilities.

Shakespeare’s Sources and Inspirations

Shakespeare drew from Saxo Grammaticus’s Gesta Danorum and earlier revenge tragedies, but his innovation was in deepening the psychological complexity of his characters. Hamlet’s introspective soliloquies, unlike the action-driven dialogue of earlier works, gave the play its philosophical edge. By blending Danish folklore with Renaissance humanism, Shakespeare crafted lines that resonate universally.

How to Understand and Appreciate Hamlet’s Lines Today

Reading Hamlet with Fresh Eyes

Approaching Hamlet for the first time—or revisiting it—can feel daunting due to its Elizabethan language. However, its famous lines are accessible with the right tools. Start by reading slowly, focusing on the rhythm of iambic pentameter, which mirrors natural speech. Visualize the scene: imagine Hamlet clutching Yorick’s skull or pacing alone during “To be, or not to be.” Annotated editions, like the Folger Shakespeare Library’s version, provide glossaries and context for unfamiliar terms. Online resources, such as No Fear Shakespeare, offer modern translations alongside the original text, making the language less intimidating. For deeper engagement, listen to audio performances—David Tennant’s 2009 RSC recording brings the lines to life with emotional clarity.

Tip: Break soliloquies into smaller chunks. For example, parse “To be, or not to be” by focusing on each clause: “to suffer / The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune” becomes a vivid image of enduring life’s hardships.

Applying Hamlet’s Wisdom in Modern Life

Hamlet’s lines offer more than literary beauty; they provide frameworks for personal reflection. “To be, or not to be” can inspire decision-making: when faced with a tough choice, weigh the “slings and arrows” (risks) against the potential “consummation” (resolution). This soliloquy encourages mindfulness, urging us to pause and reflect rather than act impulsively. Similarly, “Alas, poor Yorick” reminds us to stay grounded in the face of mortality. Journaling about these themes—perhaps writing how Yorick’s skull prompts thoughts of legacy—can make Hamlet’s insights actionable.

Example: A professional facing burnout might use “To be, or not to be” to evaluate whether to push through or pivot careers, listing pros and cons as Hamlet does with life and death.

Teaching and Sharing Hamlet’s Lines

Educators and book club leaders can make Hamlet’s lines engaging by focusing on their emotional resonance. Create discussion prompts like, “How does ‘Something is rotten’ reflect modern societal issues?” Encourage students to perform short excerpts, emphasizing tone and gesture to internalize the language. For book clubs, host a “quote-off” where members share their favorite lines and debate their meanings. A downloadable discussion guide, with questions like “How does ‘The lady doth protest too much’ apply to today’s media?” can spark lively conversations.

Resource: Visit williamshakespeareinsights.com for a free Hamlet quote discussion guide, tailored for classrooms and reading groups.

Common Misconceptions About Hamlet’s Famous Lines

Misquoted or Misunderstood Lines

Even Hamlet’s most famous lines are sometimes misquoted. For instance, “To be, or not to be” is occasionally shortened to “To be or not to be,” losing its rhythmic balance. Another misconception surrounds Hamlet’s madness: some assume lines like “Get thee to a nunnery” prove he’s genuinely unhinged, but scholars like Margreta de Grazia argue his madness is a calculated act to unsettle others. Clarifying these nuances helps readers appreciate the text’s depth.

Example: The phrase “methinks” in “The lady doth protest too much” is often omitted in casual use, diluting its skeptical tone. Always include the full quote for accuracy.

Myths About Hamlet’s Intent

A common myth paints Hamlet as a straightforward tragic hero, but his complexity defies this label. His indecision in “To be, or not to be” isn’t mere weakness; it reflects a philosophical struggle between action and contemplation. Similarly, “Get thee to a nunnery” isn’t just cruelty—it may be Hamlet’s attempt to protect Ophelia from Elsinore’s corruption. Scholarly debates, such as those in The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare, highlight how Hamlet’s ambiguity fuels his enduring appeal.

Expert Insight: Professor Emma Smith notes that Hamlet’s contradictory nature—philosopher, avenger, son—makes his lines a battleground for interpretation, inviting readers to project their own experiences.

FAQs About Hamlet’s Famous Lines

What is the most famous line in Hamlet, and why?

“To be, or not to be, that is the question” is arguably the most famous, thanks to its universal exploration of existence. Its concise yet profound phrasing resonates across cultures, appearing in everything from philosophical treatises to social media captions. Its fame stems from its accessibility—anyone grappling with a tough choice can relate.

How can I memorize Hamlet’s lines for study or performance?

Memorization is easier with techniques like chunking: break “To be, or not to be” into phrases (“To be / or not to be / that is the question”). Associate each line with an emotion or image—picture Hamlet’s anguish for “slings and arrows.” Recite aloud with gestures to engage muscle memory. Apps like Quizlet can also help with flashcards.

Are Hamlet’s lines relevant to non-academic readers?

Absolutely. Hamlet’s themes—grief, betrayal, self-doubt—are universal. “Something is rotten” speaks to anyone sensing corruption in their workplace or community. Non-academic readers can connect through performances or adaptations, like the 2000 film Hamlet starring Ethan Hawke, which sets the play in modern New York.

How have Hamlet’s lines influenced modern language?

Phrases like “something is rotten” and “protest too much” are embedded in English. They appear in journalism (e.g., editorials on political scandals) and casual speech (e.g., calling out insincerity). Their concise wit makes them endlessly quotable, ensuring Shakespeare’s linguistic legacy endures.

The famous lines of Hamlet—“To be, or not to be,” “Alas, poor Yorick,” and others—are more than poetic flourishes; they’re windows into the human soul. They challenge us to confront life’s big questions, from mortality to morality, and their cultural staying power proves their relevance. Whether you’re a student, a theatergoer, or simply curious, these quotes offer wisdom for navigating today’s complexities. Revisit Hamlet at a local theater, dive into an annotated edition, or share your favorite quote in the comments below. Which line speaks to you most? Join the conversation on social media with #HamletQuotes and keep Shakespeare’s words alive.