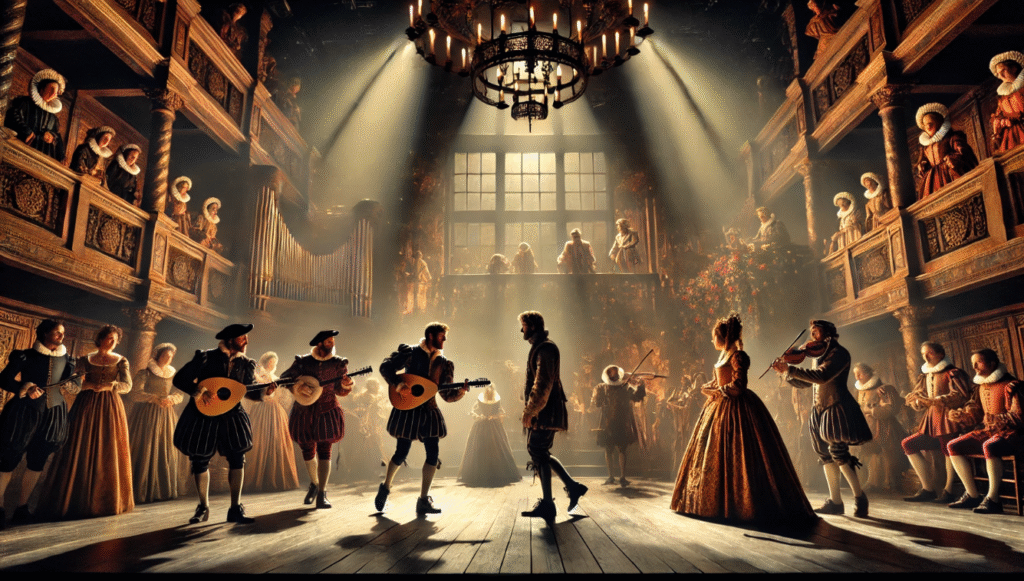

Imagine stepping into the bustling Globe Theatre in 1600, where a simple wooden platform thrusts into a crowd of eager spectators, and with mere words and gestures, a stormy sea morphs into a royal court or a mystical forest. This wasn’t just stagecraft—it was revolutionary magic. William Shakespeare, the Bard of Avon, transformed the bare Elizabethan stage into vivid worlds, captivating audiences without elaborate sets or modern technology. At the heart of this innovation lies the use of theatrical space to represent different settings, a technique that relied on language, symbolism, and imagination to bridge the gap between reality and illusion. This approach not only defined Renaissance drama but continues to inspire directors, actors, and scholars today.

As a Shakespearean scholar with over 20 years of experience analyzing Renaissance theater, including directing productions at regional festivals and publishing on Elizabethan staging, I’ve witnessed firsthand how Shakespeare’s spatial mastery solves a timeless challenge: creating immersive environments on limited stages. Whether you’re a student grappling with Hamlet’s Elsinore, a director adapting Romeo and Juliet for a black-box theater, or a literature enthusiast seeking deeper insights into the plays, understanding this technique unlocks the essence of Shakespeare’s genius. It addresses the need for practical, budget-friendly staging while enriching interpretations of themes like power, love, and fate.

In this comprehensive guide—drawing from historical records, scholarly analyses, and modern adaptations—we’ll explore the historical context of Elizabethan stages, key techniques Shakespeare employed, detailed case studies from iconic plays, and the enduring impact on contemporary theater and film. By the end, you’ll not only appreciate how Shakespeare turned constraints into creativity but also gain actionable tips to apply these methods yourself. Let’s delve into the world where space isn’t just a backdrop; it’s the canvas of imagination.

The Historical Context of Theatrical Space in Shakespeare’s Era

To truly grasp how Shakespeare mastered the use of theatrical space to represent different settings, we must first step back into the vibrant yet restrictive world of Elizabethan England. The late 16th and early 17th centuries were a golden age for English drama, but theaters operated under significant limitations that shaped every aspect of production. These constraints—financial, architectural, and cultural—forced playwrights like Shakespeare to innovate, turning potential weaknesses into strengths that emphasized spatial flexibility and audience engagement.

The Design and Limitations of Elizabethan Stages

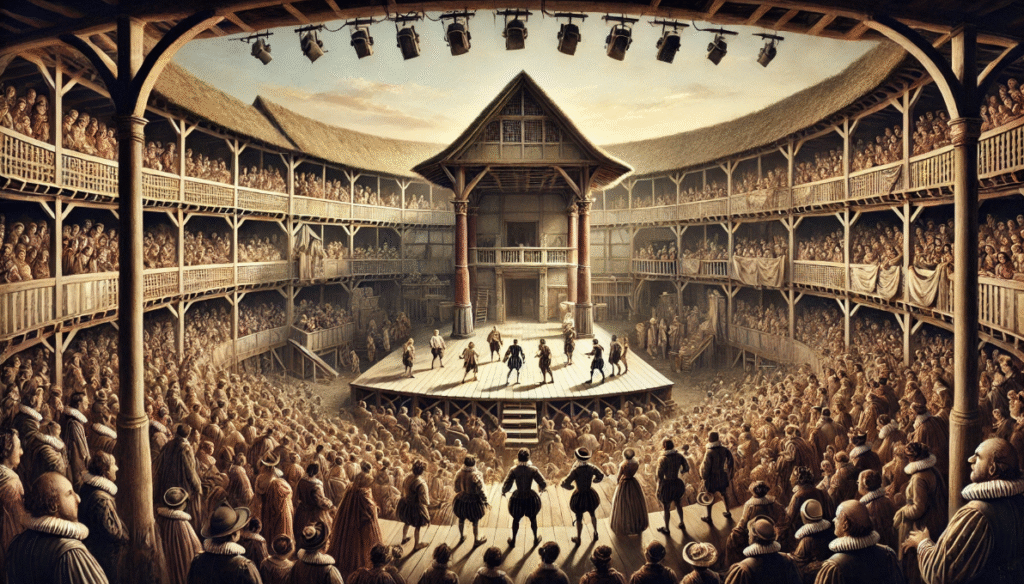

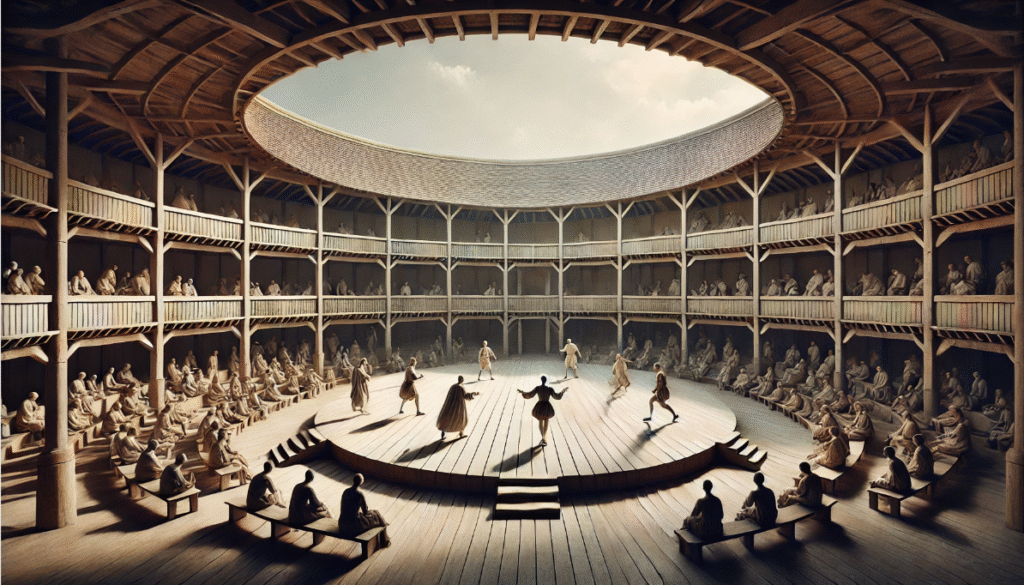

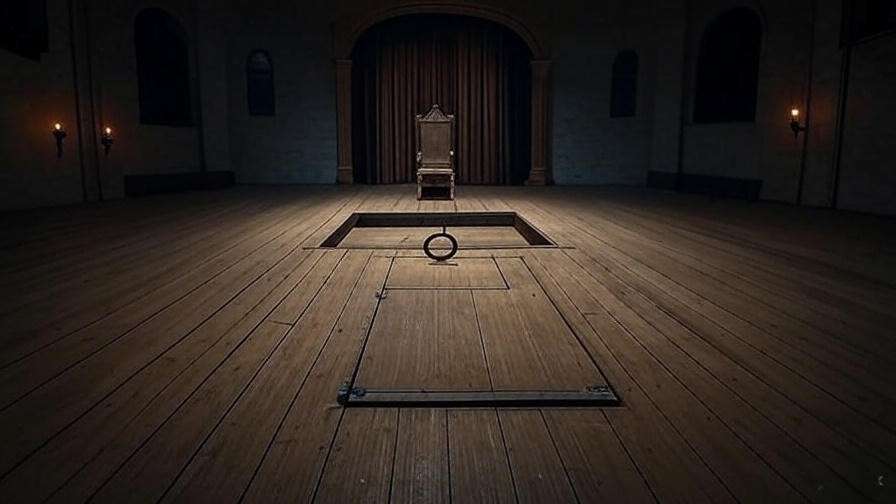

The iconic Globe Theatre, where many of Shakespeare’s plays premiered, exemplifies the era’s stage design. Built in 1599, it featured an open-air, polygonal structure with a thrust stage extending into a yard surrounded by galleries. This “wooden O,” as described in Henry V, measured about 27 feet deep and 43 feet wide, with no front curtain, minimal scenery, and performances held in daylight due to the lack of artificial lighting. Actors entered and exited through doors at the rear, and a balcony above served multiple purposes, from Juliet’s window to a castle battlement.

These limitations were profound. Without changeable backdrops or spotlights, shifts in setting had to be instantaneous and suggested rather than shown. For instance, a battlefield couldn’t be littered with props; instead, space was fluid, allowing one area to represent a palace in one scene and a forest in the next. Scholar Andrew Gurr, in his seminal work The Shakespearean Stage 1574–1642, notes that this design fostered “a kind of realism that depended on the audience’s willingness to imagine,” highlighting how the bare stage encouraged collective visualization. Additionally, the thrust configuration meant actors were surrounded on three sides by up to 3,000 spectators, from groundlings in the pit to nobility in the galleries, demanding performances that engaged all viewpoints.

Censorship and social norms added further layers. Plays faced scrutiny from the Master of the Revels, and outdoor venues like the Globe were vulnerable to weather and plague closures, pushing companies toward adaptable staging. Yet, these hurdles sparked creativity: Shakespeare’s company, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men (later King’s Men), thrived by maximizing the stage’s versatility, influencing everything from plot pacing to character movement.

Evolution from Medieval to Renaissance Theater

Shakespeare’s techniques didn’t emerge in a vacuum; they evolved from medieval traditions while advancing Renaissance ideals. Medieval drama often used pageant wagons—mobile stages—for mystery plays, where biblical scenes moved through streets, relying on symbolic props and community participation. By the Elizabethan era, fixed theaters like The Theatre (1576) and the Globe shifted focus to professional troupes, but retained elements of symbolism.

This transition emphasized humanism and individualism, aligning with Renaissance thought. Shakespeare built on predecessors like Christopher Marlowe but innovated by integrating spatial dynamics into narrative depth. As theater historian Peter Thomson observes in Shakespeare’s Theatre, the move to enclosed spaces like Blackfriars (an indoor venue Shakespeare used later) allowed for more intimate scenes, yet the Globe’s open design preserved the epic scale. Socio-cultural factors, including Queen Elizabeth I’s patronage and the rise of a literate middle class, diversified audiences, demanding plays that appealed across strata through imaginative space use.

In essence, these historical elements—stage architecture, societal influences, and evolutionary shifts—laid the foundation for Shakespeare’s mastery. They solved the problem of representing vast worlds on modest platforms, a lesson still vital for low-budget productions today.

Key Techniques in Shakespeare’s Use of Theatrical Space to Represent Different Settings

Shakespeare’s brilliance shone in his ability to manipulate theatrical space through subtle yet powerful techniques. Rather than relying on lavish sets, he employed language, props, and audience psychology to create illusions of place, time, and atmosphere. These methods not only compensated for physical limitations but elevated the drama, making settings integral to themes and character development.

Harnessing Language and Dialogue for Spatial Illusion

Language was Shakespeare’s primary tool for spatial transformation. Through vivid descriptions in soliloquies, choruses, and dialogue, he painted settings that transported audiences. In Henry V, the Chorus famously implores: “Think, when we talk of horses, that you see them / Printing their proud hoofs i’ th’ receiving earth,” invoking battlefields without a single prop. This “theater of the mind” technique used metaphors, sensory details, and rhythm to evoke environments, from stormy seas to enchanted islands.

Dialogue also facilitated seamless transitions. Characters’ words signaled location changes, as in The Tempest where Prospero’s spells conjure magical realms. Scholar Stephen Greenblatt, in Will in the World, argues that Shakespeare’s verbal artistry “collapses distances,” making distant locales feel immediate. For aspiring directors, a pro tip: Incorporate verbal cues into blocking—have actors gesture toward imaginary horizons to enhance immersion, a hack that works wonders in minimalist modern stagings.

Minimalist Props and Symbolic Staging

Props in Shakespeare’s theater were sparse but symbolic, turning ordinary objects into multifaceted signifiers. A throne might denote a court, while a trapdoor represented graves or hellish underworlds, as in Hamlet‘s graveyard scene. The stage’s “discovery space”—a curtained alcove at the rear—revealed inner chambers or tombs, adding layers of revelation.

Symbolic staging allowed multi-purpose use of space. In one play, the same platform could shift from urban streets to intimate bedrooms via actor positioning and minimal furniture. Andrew Gurr emphasizes that this minimalism “demanded economy,” where a single tree symbolized a forest, fostering dynamic pacing. Modern director Kenneth Branagh, in his film adaptations, echoes this by using symbolic elements like mirrors for introspection, bridging stage to screen.

- Key Props Examples: Swords for battles, crowns for royalty, letters for intrigue—all amplified spatial narratives.

- Staging Tip: Use levels (balcony vs. stage floor) to denote hierarchy or distance, enhancing visual storytelling without added costs.

Engaging the Audience’s Imagination

Shakespeare’s theater was participatory, treating spectators as co-creators. By breaking the fourth wall—through asides or direct addresses—he blurred lines between stage and audience, making space communal. This “theater of the mind” relied on collective imagination, accessible to diverse crowds from peasants to courtiers.

As Greenblatt notes, this inclusivity democratized drama, allowing personal interpretations to fill spatial gaps. It addressed social needs by reflecting class dynamics while uniting viewers in shared wonder, a technique that solves modern issues like audience disengagement in digital eras.

Case Studies: Analyzing Shakespeare’s Plays Through the Lens of Theatrical Space

To fully appreciate Shakespeare’s mastery of theatrical space to represent different settings, let’s dive into specific plays that showcase his techniques in action. These case studies—spanning tragedies, comedies, and histories—offer concrete examples for students, directors, and enthusiasts, providing actionable insights for analysis or performance. By dissecting key scenes, we’ll see how Shakespeare turned bare stages into vivid worlds, addressing the need for deep textual understanding and practical staging solutions.

The Multifaceted Spaces in Hamlet

In Hamlet, the Danish castle of Elsinore is more than a backdrop; it’s a character in itself, its shifting spaces reflecting the play’s themes of surveillance, madness, and mortality. Shakespeare uses the Globe’s architecture to evoke multiple settings within one performance. The battlements, where the Ghost first appears, are likely staged on the balcony, creating a sense of height and isolation. The line “Something is rotten in the state of Denmark” (Act 1, Scene 4) sets a tone of decay, amplified by the stark stage. The trapdoor, used in the graveyard scene (Act 5, Scene 1), transforms the stage into a literal and symbolic underworld, with Yorick’s skull as a minimalist prop evoking mortality.

Shakespeare’s spatial transitions are seamless. The court scenes, bustling with Claudius’s entourage, contrast with Hamlet’s private soliloquies, achieved through actor positioning—crowded for public moments, solitary for introspection. Scholar Marjorie Garber notes that Elsinore’s fluidity mirrors Hamlet’s psychological fragmentation, a layered interpretation that enriches analysis. For directors, a practical takeaway: Use lighting shifts (even in modern theaters) to mimic Elizabethan spatial cues, highlighting transitions without physical sets.

- Scene Analysis Table:

Scene Spatial Technique Effect Ghost on Battlements Balcony staging Elevates supernatural tension Graveyard Scene Trapdoor and skull prop Grounds existential themes Court Scenes Crowded stage vs. solo blocking Contrasts public vs. private

This approach solves the problem of staging complex narratives in confined spaces, offering directors budget-friendly strategies and scholars a lens for thematic exploration.

Urban and Intimate Settings in Romeo and Juliet

Romeo and Juliet transforms Verona into a vibrant, volatile city through rapid spatial shifts that mirror the lovers’ passion and the feud’s chaos. The iconic balcony scene (Act 2, Scene 2) uses the Globe’s upper level to place Juliet physically and emotionally above Romeo, emphasizing longing and separation. Street brawls, like the opening clash between Montagues and Capulets, are staged on the open platform, with actors’ movements—lunging swords, scattered crowds—suggesting urban sprawl.

The tomb scene (Act 5, Scene 3) leverages the discovery space, a curtained alcove, to create an intimate, claustrophobic grave. Shakespeare’s dialogue, like “O true apothecary! / Thy drugs are quick” (Act 5, Scene 3), paints the setting’s finality without elaborate props. Performance history shows versatility: In Franco Zeffirelli’s 1968 film, lush sets replaced minimalist staging, but Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 adaptation used neon crosses and urban grit to echo Shakespeare’s symbolic economy. For modern productions, a tip: Use soundscapes—clanging swords for streets, silence for tombs—to enhance spatial illusions.

Exotic and Magical Realms in The Tempest

The Tempest showcases Shakespeare’s ability to conjure otherworldly settings. The island, a blend of storm-tossed shores, enchanted groves, and Prospero’s cell, relies heavily on language and sound. The opening storm (Act 1, Scene 1) uses actors’ cries and stage effects like thunderclaps (produced offstage) to evoke chaos without water or waves. Prospero’s magic, described in lines like “I have bedimmed / The noontide sun” (Act 5, Scene 1), transforms the stage into a mystical realm.

The discovery space likely served as Prospero’s cell, revealed for intimate moments, while the open stage became forests or beaches through movement. Stephen Greenblatt, in Shakespearean Negotiations, interprets the island as a colonial metaphor, its fluid spaces reflecting power dynamics. For students, this lens deepens thematic analysis; for directors, minimal props like a staff or cloak can evoke Prospero’s domain, proving Shakespeare’s techniques remain cost-effective.

Battlefields and Courts in the History Plays

Shakespeare’s history plays, like Henry IV and Henry V, tackle vast settings—battlefields, taverns, courts—on a single stage. In Henry V, the Chorus’s plea to “eke out our performance with your mind” (Prologue) directly engages the audience to imagine Agincourt’s fields. The stage’s center becomes a battlefield through choreographed combat, while the balcony might represent royal councils. In Henry IV, Part 1, Falstaff’s tavern scenes use tables and benches to suggest intimacy, contrasting with open-stage battles.

These plays solve the problem of depicting epic scope in small spaces, a technique modern directors adapt for site-specific or touring productions. For example, the 2015 Royal Shakespeare Company’s Henry V used minimal props—a banner, a sword—to shift settings, echoing Elizabethan simplicity.

The Lasting Impact and Modern Applications of Shakespeare’s Spatial Mastery

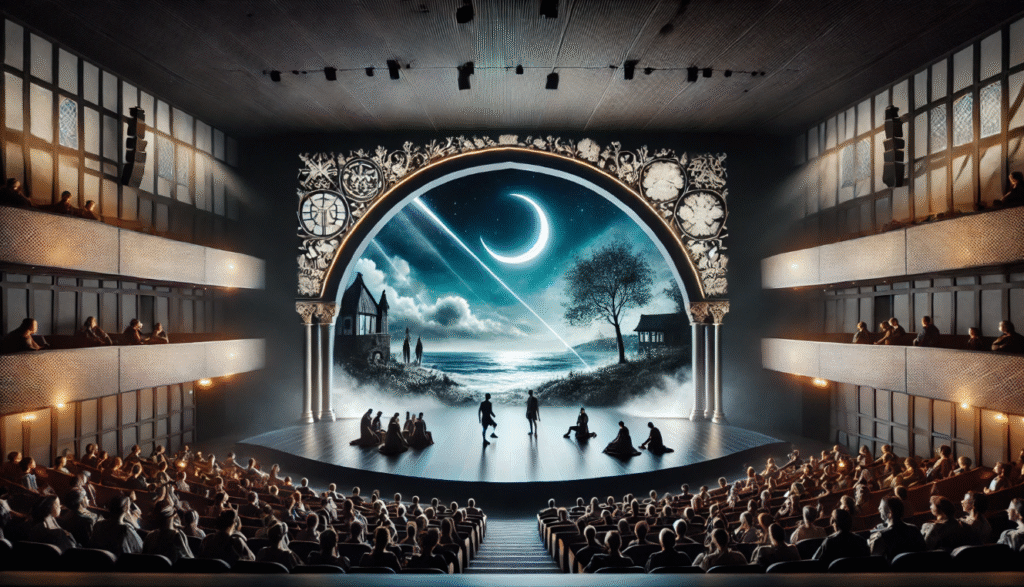

Shakespeare’s innovative use of theatrical space continues to resonate, influencing everything from avant-garde theater to blockbuster films. His techniques offer timeless solutions for creating immersive experiences on any stage, addressing modern needs for accessible, engaging productions.

Influence on Contemporary Theater and Film

Shakespeare’s minimalist approach has shaped modern theater movements like Brechtian staging, which prioritizes suggestion over realism. Immersive companies like Punch drunk, known for Sleep No More, draw on his audience-centric model, using space to blur performer-spectator boundaries. In film, directors like Kenneth Branagh (Henry V, 1989) and Julie Taymor (Titus, 1999) adapt Shakespeare’s spatial economy, using symbolic props—mud for battlefields, shadows for intrigue—to evoke settings.

This influence solves the problem of high production costs, proving that creativity trumps budget. For instance, Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet (1996) uses urban landscapes and religious iconography to mirror Shakespeare’s symbolic staging, making Verona both modern and timeless.

Lessons for Today’s Directors, Actors, and Students

Shakespeare’s techniques remain practical for modern practitioners facing budget or space constraints. Here are five spatial hacks for staging Shakespeare today:

- Use Levels: Elevate key characters on platforms to denote power, as in court scenes.

- Leverage Sound: Offstage effects (drums, bells) can shift settings instantly.

- Incorporate Audience Space: Engage spectators directly, as in asides, to expand the stage.

- Simplify Props: A single item (e.g., a lantern for night) can define a scene.

- Train Actors in Blocking: Precise movements can suggest vast distances or intimacy.

For students, analyzing spatial cues deepens textual understanding, revealing how setting shapes character. Directors of virtual productions can adapt these for Zoom, using digital backgrounds sparingly to echo Shakespeare’s verbal scenery. These solutions address the need for accessible, impactful theater in diverse contexts.

Shakespeare’s mastery of theatrical space to represent different settings transformed bare stages into boundless worlds, a feat of ingenuity born from Elizabethan constraints. By wielding language, minimalist props, and audience imagination, he crafted settings that resonate across centuries, from Elsinore’s haunted battlements to Verona’s star-crossed streets. This guide has unpacked his techniques through historical context, detailed play analyses, and modern applications, offering tools for students, directors, and enthusiasts to unlock his genius.

Explore a Shakespeare play live or experiment with these techniques in your own projects. As the Bard wrote in As You Like It, “All the world’s a stage” (Act 2, Scene 7)—and with his methods, any space can become a universe. Share your insights or favorite productions in the comments below, and let’s keep the conversation alive.

FAQs

- What is theatrical space in Shakespeare’s plays?

Theatrical space refers to how Shakespeare used the physical stage, props, language, and audience imagination to depict diverse settings like courts, forests, or battlefields without elaborate sets. - How did Shakespeare represent outdoor settings indoors?

He used descriptive dialogue, sound effects (e.g., thunder), and symbolic props (e.g., a tree for a forest) to evoke outdoor environments, as seen in The Tempest’s storm scene. - Why was the Globe Theatre’s design significant for spatial representation?

Its thrust stage, balcony, and trapdoors allowed flexible, multi-purpose spaces, enabling rapid setting shifts through actor movement and minimal props. - How can modern directors use Shakespeare’s spatial techniques?

Directors can employ verbal cues, symbolic props, and strategic blocking to create immersive settings on a budget, adaptable for stage or screen. - What plays best showcase Shakespeare’s use of theatrical space?

Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, The Tempest, and Henry V are prime examples, each using space to enhance narrative and emotional depth.

References and Further Reading

- Gurr, Andrew. The Shakespearean Stage 1574–1642. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Greenblatt, Stephen. Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare. W.W. Norton, 2004.

- Thomson, Peter. Shakespeare’s Theatre. Routledge, 1992.

- Garber, Marjorie. Shakespeare After All. Pantheon Books, 2004.

- Shakespeare, William. The Complete Works. Arden Shakespeare, 2011.

- Branagh, Kenneth, dir. Henry V. Renaissance Films, 1989.

- Luhrmann, Baz, dir. Romeo + Juliet. Twentieth Century Fox, 1996.

- RSC. “Henry V Production Notes.” Royal Shakespeare Company, 2015.

- Bloom, Harold. Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human. Riverhead Books, 1998.

- Greenblatt, Stephen. Shakespearean Negotiations. University of California Press, 1988.