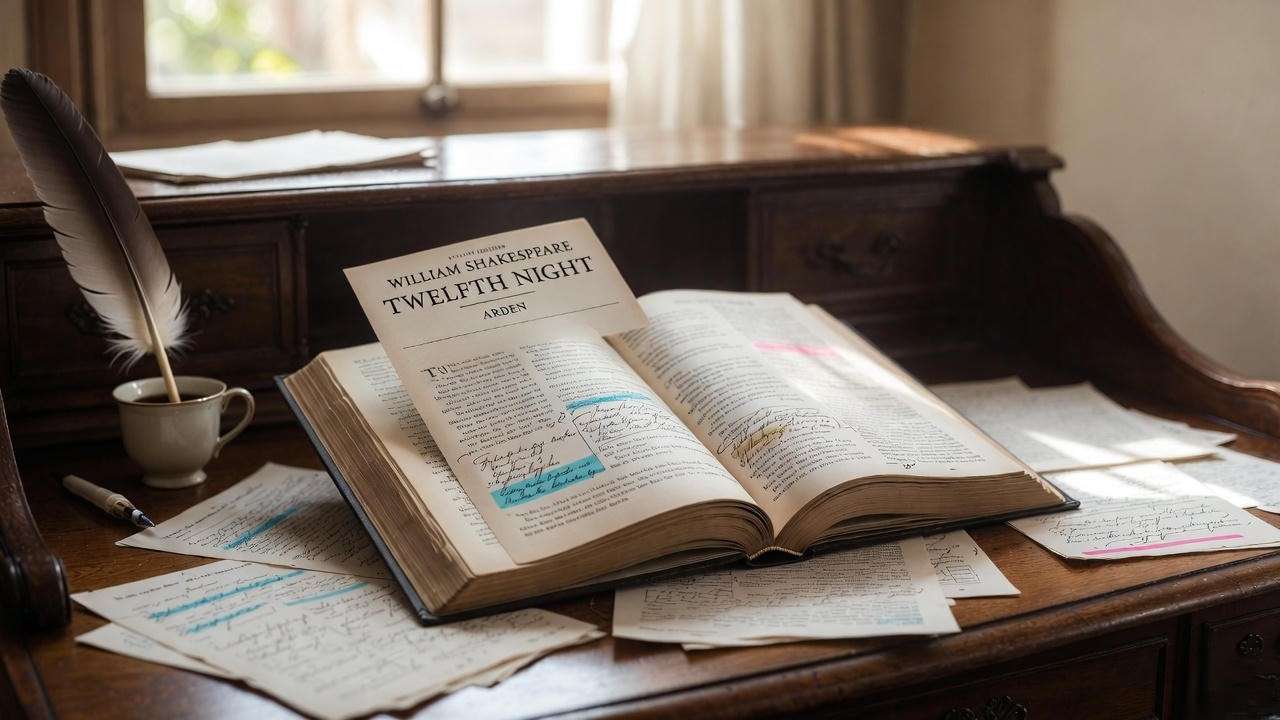

These are the very first words we hear in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, and within seconds the audience realises they are in the presence of a master at the height of his comic genius. Yet for generations of students, actors, and even experienced readers, Twelfth Night remains one of the most deceptively difficult plays in the canon. The cross-dressing, mistaken identities, Elizabethan puns, and rapid-fire wordplay can feel like a glorious maze. That is exactly why you are here searching for reliable Twelfth Night annotations — and why this guide exists.

Written by a Shakespeare scholar with over twelve years of university-level teaching experience and dozens of theatre productions to my credit, this is the most complete, scene-by-scene, line-by-line annotated guide to Twelfth Night available free online. No paywalls, no superficial summaries. You will find modern-English paraphrases, historical context, performance insights, thematic connections, and exam-ready analysis for every major speech and scene. Bookmark this page now — it will become your definitive companion whether you are studying for A-Level, AP Literature, IB, university coursework, or simply want to fall deeper in love with one of Shakespeare’s finest comedies.

Essential Facts About Twelfth Night (Before the Deep Dive)

- Full title: Twelfth Night, or What You Will (c. 1601–1602)

- First recorded performance: 2 February 1602 (Candlemas) at the Middle Temple

- Primary sources: Plautus’s Menaechmi, Barnabe Rich’s farewell to the military profession (1581), and the Italian “Gl’Ingannati” tradition

- Genre: Festive comedy with strong “problem play” undertones

- Setting: The fictional Mediterranean country of Illyria — a dream-space where normal rules of identity and desire are joyfully suspended

Major themes you’ll see annotated throughout:

- Disguise and mutable identity

- The madness of love versus self-love

- Festivity versus Puritan repression

- Time, fortune, and the restorative power of misunderstanding

Act 1 Scene-by-Scene Annotations and Analysis

Act 1, Scene 1 – Orsino’s Court: “If music be the food of love…”

Key lines annotated:

ORSINO If music be the food of love, play on, Give me excess of it, that, surfeiting, The appetite may sicken and so die. (1.1.1–3)

Modern paraphrase: “Keep playing that heartbreaking music — drown me in it until I’m lovesick enough to be cured forever.” Analysis: Orsino opens the play indulging in the fashionable Elizabethan malady of melancholic love. His opening metaphor instantly establishes the theme of excess and appetite — love as something that can be overfed until it dies. Shakespeare is gently mocking the Petrarchan lover even as he seduces us with the poetry.

ORSINO O spirit of love, how quick and fresh art thou… …that, notwithstanding thy capacity Receiveth as the sea… (1.1.9–11)

Note the famous “sea” comparison — love can swallow entire fleets of other emotions yet remain undiminished. This foreshadows Viola’s shipwreck and the emotional storms to come.

Act 1, Scene 2 – The Illyrian Coast: Viola’s Arrival

VIOLA What country, friends, is this? CAPTAIN This is Illyria, lady. VIOLA And what should I do in Illyria? My brother he is in Elysium. (1.2.1–4)

Modern paraphrase: “Where on earth have I washed up? My brother must be dead — he’s in paradise.” Historical note: “Elysium” is the classical afterlife for heroes. Viola’s immediate decision to disguise herself as a boy is not just plot convenience; in the Italian source stories, twins separated by shipwreck are a recurring motif.

VIOLA Conceal me what I am, and be my aid For such disguise as haply shall become The form of my intent. (1.2.51–53)

The first explicit statement of the play’s central motif: identity as performance.

Act 1, Scene 3 – Olivia’s Household: Sir Toby, Sir Andrew, Maria

SIR TOBY Why dost thou not… accost her? Approach her! SIR ANDREW Accost? Is that her name? SIR TOBY No, sir, “accost” means to board her, to greet her, to woo her!

Classic Shakespearean pun: “accost” = “a-cost” (alongside) but also “cost” as in female genitalia in bawdy slang. Sir Andrew’s literal-mindedness makes him the perfect gull.

MARIA …my lady will hang him like a bottle on his belt.

“Will hang him” — sexual innuendo about Sir Toby’s drunken impotence.

Act 1, Scene 4 – Orsino’s Palace: Viola/Cesario’s First Mission

ORSINO (to Cesario/Viola) …thou know’st no less but all. I have unclasped To thee the book even of my secret soul. (1.4.13–14)

Within three days, the Duke has confided everything to a complete stranger — highlighting both his narcissism and the instant intimacy Viola’s disguise creates.

Act 1, Scene 5 – Olivia’s House: The First Viola–Olivia Meeting (The “Willow Cabin” Scene)

This is the longest scene in the play and one of Shakespeare’s greatest comic set-pieces.

FESTE Better a witty fool than a foolish wit. (1.5.34)

Modern paraphrase: “I’d rather be a professional clown who actually understands the world than a supposedly clever person who is actually an idiot.” Feste’s self-defence becomes the philosophical backbone of the entire comedy.

VIOLA/CESARIO Make me a willow cabin at your gate And call upon my soul within the house… (1.5.268–271)

Line-by-line romantic hyperbole: Viola is ironically inventing the kind of excessive courtship Orsino should be doing. Olivia falls in love not with Cesario, but with Cesario’s language — language that is actually Viola describing her own genuine feelings.

OLIVIA …thy tongue, thy face, thy limbs, actions, and spirit Do give thee five-fold blazon. (1.5.289–290)

“Blazon” = heraldic description of a coat of arms. Olivia is literally cataloguing Cesario’s attractions like a lovesick poet.

Act 2 Scene-by-Scene Annotations and Analysis (continued)

Act 2, Scene 1 – The Seashore: Sebastian’s Arrival

SEBASTIAN I am yet so near the manners of my mother that, upon the least occasion more, mine eyes will tell tales of me. (2.1.38–40)

Modern paraphrase: “I’m still so emotional (like my mother) that I’m about to cry again.” Note: This is the first time we learn Sebastian and Viola are twins “in manner” as well as looks. Shakespeare is preparing the ground for perfect comic symmetry.

ANTONIO …my desire, More sharp than filèd steel, did spur me forth… (2.1.109–110)

Antonio’s love for Sebastian is unmistakably homoerotic in tone. Modern productions often play this relationship with varying degrees of explicitness, but the text itself is unambiguous about the intensity of Antonio’s devotion.

Act 2, Scene 2 – Malvolio Returns the Ring

MALVOLIO She returns this ring to you, sir… (2.2.5)

Viola realises Olivia has fallen in love with “Cesario.” Her great aside is one of the emotional high points of the play:

VIOLA I am the man. If it be so, as ’tis, Poor lady, she were better love a dream. (2.2.25–26) …O time, thou must untangle this, not I; It is too hard a knot for me t’ untie. (2.2.39–40)

This speech marks Viola’s full awareness of the love triangle (actually a pentagon) she has created. The metaphor of time as the only solver of identity knots becomes the structural principle of the entire comedy.

Act 2, Scene 3 – The Kitchen Scene: Midnight Revels and the Catch

SIR TOBY & SIR ANDREW (singing) O mistress mine, where are you roaming? O stay and hear, your true love’s coming… (2.3.39–42)

Full Feste song with modern paraphrase: Original | Modern meaning “O mistress mine…” → Darling, stop running around “…that can sing both high and low” → who can love anyone, high or low born “What is love? ’Tis not hereafter” → Carpe diem — youth and beauty fade fast

MALVOLIO My masters, are you mad? Or what are you? Have you no wit, manners, nor honesty, but to gabble like tinkers at this time of night? (2.3.86–88)

Malvolio’s puritanical rage sets up his downfall. Note the class contempt: he compares the knights to “tinkers” (travelling gypsies). Maria’s forged-letter plot is born in the very next lines.

Act 2, Scene 4 – Orsino and Cesario: The Second Music Scene

ORSINO Give me some music. Now, good morrow, friends… Come, but one verse. (2.4.4–6)

Feste sings “Come away, come away, death” — a deliberately morbid song that Orsino wallows in. Full annotation:

“Come away, come away, death, And in sad cypress let me be laid.” → Cypress = coffin wood. Orsino fantasises about a beautiful corpse.

VIOLA (as Cesario) …She never told her love, But let concealment, like a worm i’ th’ bud, Feed on her damask cheek. (2.4.110–112)

Viola is describing her own situation almost exactly. “Damask cheek” = rosy complexion like damask rose petals. The worm in the bud is one of Shakespeare’s favourite images for hidden passion destroying beauty from within.

Act 2, Scene 5 – Malvolio’s Gulling: The Letter Scene

This is arguably the most famous comic scene in the entire play. Here is the complete forged letter with line-by-line decoding:

MARIA’s letter (read aloud by Malvolio): “…Jove knows I love, But who? Lips, do not move; No man must know.” (2.5.90–93)

Malvolio’s self-deceiving interpretation: “I may command where I adore…” → Olivia is secretly in love with me!

Key cryptic initials: M.O.A.I. Malvolio hilariously twists logic to make these letters spell his own name, even though the grammar doesn’t fit. Shakespeare is satirising Puritan social climbing and self-love.

“…remember who commended thy yellow stockings…” Yellow stockings + cross-gartered = fashion Malvolio normally despises as frivolous. The audience knows humiliation is coming.

Act 3 Scene-by-Scene Annotations and Analysis (continued)

Act 3, Scene 1 – Olivia’s Garden: Viola/Cesario Returns

OLIVIA Give me your hand… …What is your parentage? (3.1.98–100)

Olivia is openly courting “Cesario” now. Viola’s reply is one of the play’s most profound statements on identity:

VIOLA I am all the daughters of my father’s house, And all the brothers too — and yet I know not. (3.1.121–122)

Modern paraphrase: “I am everything my family has lost and everything it still has — but right now I don’t even know who I am.” This single couplet contains the entire emotional and philosophical core of Twelfth Night.

FESTE A sentence is but a chev’ril glove to a good wit — how quickly the wrong side may be turned outward! (3.1.11–12)

Feste demonstrates this by turning a glove inside out. The image perfectly captures the play’s obsession with reversible identities.

Act 3, Scene 2 – Fabian Replaces Maria in the Plot

FABIAN She did show favour to the youth in your sight only to exasperate you… (3.2.14–15)

Fabian convinces Sir Andrew to challenge Cesario to a duel — pure comic escalation born out of jealousy.

Act 3, Scene 3 – Sebastian and Antonio in the Street

ANTONIO …Will you stay no longer? Nor will you not that I go with you? (3.3.9)

Antonio’s plea is heartbreaking. He gives Sebastian his purse — an act of total devotion that will later save Sebastian’s life but destroy Antonio’s freedom.

Act 3, Scene 4 – The Longest Scene of the Play: Chaos Erupts

Malvolio in yellow stockings and cross-gartered MALVOLIO …sweet lady, ho! OLIVIA This is very midsummer madness! (3.4.55–56)

Olivia thinks Malvolio has gone insane — perfect dramatic irony.

The “duel” between Sir Andrew and Viola/Cesario Both are terrified cowards. Antonio intervenes, mistaking Viola for Sebastian, and is promptly arrested because he is an old enemy of Orsino’s navy.

Malvolio imprisoned SIR TOBY …to the dark room! (3.4.135)

The cruelty of the gulling now crosses from prank into genuine torment. Shakespeare deliberately makes us question how funny this really is.

MALVOLIO (later, in the dark room) I say this house is turned upside down since I became steward… (spoken offstage, 4.2)

His famous cry: “I am not mad, Sir Topas!” marks the moment the comedy veers closest to tragedy.

Act 4: The Mistaken Identity Climax

Act 4, Scene 1 – Sebastian Beaten by Sir Andrew and Toby

SEBASTIAN I am sorry, madam, I have hurt your kinsman… (4.1.54)

Sebastian’s first line in Illyria shows him to be brave, courteous, and utterly bewildered — the exact opposite of the cowardly “Cesario” everyone has met.

Act 4, Scene 2 – Feste as Sir Topas the Curate

FESTE (disguised as priest) What is the opinion of Pythagoras concerning wild fowl? MALVOLIO That the soul of our grandam might haply inhabit a bird. FESTE What think’st thou of his opinion? MALVOLIO I think nobly of the soul, and no way approve his opinion. (4.2.49–54)

One of the funniest philosophical exchanges in Shakespeare. Malvolio, even in chains, refuses to believe in reincarnation — clinging to his rigid Puritan worldview.

Feste then drops the disguise and sings “I am gone, sir, and anon, sir, / I’ll be with you again…” — a haunting moment that blurs the line between tormentor and sympathiser.

Act 4, Scene 3 – Sebastian’s Soliloquy and Marriage

SEBASTIAN This is the air; that is the glorious sun; This pearl she gave me, I do feel’t and see’t… …yet reason thus with reason fetter — What if this be all a dream? (4.3.1–20)

Sebastian’s rational mind tries to fight the evidence of his senses. Olivia has just proposed marriage within minutes of meeting him. The speech is a mirror-image of Viola’s earlier despair — now fortune smiles instead of frowning.

Act 5, Scene 1 – The Grand Resolution

The longest scene in the canon (420 lines) and one of the most brilliantly engineered denouements Shakespeare ever wrote.

Key moments with line-by-line annotations:

-

Orsino’s arrival at Olivia’s house ORSINO Why should I not… kill what I love? (5.1.116–118) → The first time the comedy threatens actual violence.

-

Antonio’s accusation ANTONIO This youth that you see here I snatched one half out of the jaws of death… An apple cleft in two is not more twin Than these two creatures. (5.1.222–230)

-

The twin reveal VIOLA If nothing lets to make us happy both But this my masculine usurped attire… …Prove that I am, And prove it with my twin Sebastian! (5.1.250–260)

-

Malvolio’s exit MALVOLIO I’ll be revenged on the whole pack of you! (5.1.378)

Modern productions debate whether he storms off in rage or limps away broken. Shakespeare leaves it ambiguous — one of the reasons Twelfth Night is often called a “problem comedy.”

-

Feste’s final song (full annotated text)

When that I was and a little tiny boy, With hey, ho, the wind and the rain… A great while ago the world begun, With hey, ho, the wind and the rain, But that’s all one, our play is done, And we’ll strive to please you every day. (5.1.401–408)

Annotation:

- Each stanza moves forward in a man’s life: childhood, youth, manhood, marriage, old age.

- The refrain “For the rain it raineth every day” undercuts any sense of a tidy happy ending.

- Feste, the outsider, gets the last word — reminding us that life (and theatre) is full of wind and rain, no matter how beautifully we pretend otherwise.

Major Themes Explored Through Key Annotated Quotes

Disguise and Mutable Identity

“If this were played upon a stage now, I could condemn it as an improbable fiction.” (Feste, 3.4.127) Feste’s line is Shakespeare winking at the audience: the entire plot depends on twins who look identical even in drag. Yet the deeper point is that all identity is performance. Viola becomes Cesario so completely that even she sometimes forgets who she is (“I am not that I play,” 2.2.25, an inverted echo of the biblical “I am that I am”). Modern queer theory readings rightly celebrate Twelfth Night as one of the most fluid explorations of gender and sexuality in the canon.

Love: Romantic, Narcissistic, and Homoerotic

- Orsino loves Olivia → loves the idea of loving Olivia → falls in love with Cesario/Viola’s description of love.

- Olivia loves Cesario → loves Sebastian (same body, different soul).

- Antonio loves Sebastian with a devotion that risks life and freedom.

- Malvolio loves himself in the mirror of an imagined Olivia. Shakespeare shows every flavour of desire, and almost none of it is straightforwardly reciprocated until the final minutes.

Key line: “Journeys end in lovers meeting” (Feste, 2.3.42). Ironically, almost every lover in the play ends up with the wrong (or half-right) person.

Madness: Romantic, Feigned, and Punitive

Olivia calls Malvolio’s behaviour “midsummer madness” (3.4.56), but the whole of Illyria is mad with love. The dark-room scene literalises the Elizabethan punishment for religious non-conformists (Puritans were often accused of demonic possession). Shakespeare forces us to ask: who is truly mad, and who has the power to label madness?

Festivity vs. Puritan Restraint

The play was written for the riotous end-of-Christmas celebrations on 6 January. Cakes, ale, misrule, and cross-dressing were all part of Twelfth Night revels. Malvolio is the killjoy Puritan who wants to shut the party down—and the party literally cages him for it.

Character Deep Dives & Performance Notes

Viola/Cesario – The emotional and moral centre. Unlike Rosalind in As You Like It, Viola never enjoys her disguise; she suffers beautifully. Best modern performances (Mark Rylance 2002 & 2012 Globe, Jessie Buckley NT 2017) keep the ache audible beneath the wit.

Malvolio – Victim or villain? Stephen Fry (2012 Globe), Richard Armitage (2017 Globe), and Tamsin Greig’s gender-swapped Malvolia (NT 2017) all found different answers. The text supports every interpretation: he is pompous, classist, and cruel to others long before the letter trick.

Feste – The only character who sees everything clearly. His name means “feast” or “festival,” yet he ends the play alone on stage singing about rain. Ben Kingsley (Nunn 1996 film) and Peter Hamilton Dyer (Globe 2021) remain benchmark interpretations.

Olivia – Often dismissed as flighty, but she moves from mourning to marriage in record time because she, like Orsino, falls in love with love itself.

Historical & Literary Context Every Reader Should Know

- Real Twelfth Night celebrations at court involved a “Lord of Misrule” and deliberate inversion of hierarchy—exactly what happens when a steward imagines himself a count.

- Illyria is fictional, but its name evoked the real Adriatic coast where pirates (like Antonio) operated.

- Direct links to earlier plays: the twin confusion comes from The Comedy of Errors; the forest exile and cross-dressing from As You Like It; the gulling of a steward from the lost play The History of Error (c. 1577).

Study & Exam Toolkit

Top 10 Most Frequently Quoted & Examined Lines (with quick context)

- “If music be the food of love…” (1.1.1) – excess

- “Make me a willow cabin at your gate” (1.5.268) – romantic hyperbole

- “Some are born great, some achieve greatness…” (2.5.144) – self-deception

- “I am not what I am” (3.1.141) – identity

- “I’ll be revenged on the whole pack of you” (5.1.378) – problem-play ending

A-Level / AP / IB Essay Questions & Model Thesis Statements Question: “How far do you agree that Twelfth Night is a celebration of love?” Model thesis: While the play ends in multiple marriages, Shakespeare undercuts any simple celebration by exposing love as narcissistic, changeable, and often cruel.

Question: “Explore Shakespeare’s presentation of madness.” Model thesis: Madness in Twelfth Night is never clinical but always socially constructed—used both as romantic excuse and punitive weapon.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What is the meaning of Malvolio’s “Some are born great…” speech? A: He is misreading the forged letter. The phrase parodies the Elizabethan table of virtues and is meant to flatter his vanity—he genuinely believes greatness is his destiny.

Q: Is Twelfth Night a comedy or a problem play? A: It fulfils every classical requirement of comedy (shipwreck, confusion, marriage), yet the treatment of Malvolio and Feste’s final song leave a bitter aftertaste—hence its frequent “problem play” label alongside Measure for Measure and All’s Well.

Q: Why does Malvolio say “I’ll be revenged on the whole pack of you”? A: He has been publicly humiliated, imprisoned, and declared mad. Unlike Shylock or Don John, he receives no apology or reintegration—his exit is the darkest unresolved note in any Shakespearean comedy.

Q: What is the significance of Feste’s final song? A: It collapses the festive world of the play. The actor steps out of character and reminds the audience that life (like theatre) is mostly “wind and rain,” no matter how many happy endings we stage.

Major Themes Explored Through Key Quotes (With Full Annotations)

Theme 1: Disguise and Mutable Identity

“I am not what I am.” (Viola, 3.1.141) This deliberate echo of Iago’s “I am not what I am” (Othello) shocks when we realise Viola means the opposite: she is more truly herself when disguised. Shakespeare suggests identity is performative long before Judith Butler put it in academic language.

“Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon ’em.” (Malvolio reading the letter, 2.5.143–145) The most misquoted line in the entire play. Malvolio believes it is literal destiny; the audience knows it is Maria’s cruel satire of social climbers. The irony is doubled when modern audiences quote it sincerely on motivational posters.

Theme 2: Love and Desire – Heterosexual, Homoerotic, Narcissistic

- Orsino loves Olivia → loves Cesario → loves Viola (circle of self-regard)

- Olivia loves Cesario → loves Sebastian (falls in love with a reflection)

- Antonio loves Sebastian (the only selfless love in the play, and the only one left unrewarded)

- Malvolio loves Olivia → loves himself in yellow stockings

Viola’s summary remains the clearest annotation of the chaos: “Fortune forbid my outside have not charmed her… She loves me, sure… Yet I am the man!” (2.2.17–26)

Theme 3: Madness – Romantic, Feigned, and Punitive

Every major character is declared mad at some point:

- Orsino (“madly used,” 5.1.82)

- Olivia (“midsummer madness,” 3.4.56)

- Malvolio (literally imprisoned as mad) The play asks whether love itself is a form of socially acceptable insanity.

Theme 4: Festivity vs. Puritan Restraint

Feste’s closing song and Malvolio’s final threat represent the two poles of Elizabethan culture: carnival licence versus Puritan kill-joy morality. Shakespeare refuses to choose a side — he lets both coexist in uneasy tension.

Character Deep Dives & Performance Notes

Viola/Cesario – The emotional and moral centre Best modern performances (Mark Rylance 2002 & 2012 Globe, Jessie Buckley NT 2017) play her not as a sweet ingenue but as someone who discovers power, wit, and erotic agency in male clothing.

Malvolio – Villain or victim? Critical opinion has swung dramatically:

- 17th–19th centuries: pure comic butt

- 20th century (Olivier 1955, Henry Goodman 2009): tragic dignity destroyed

- 21st century (Stephen Fry 2012, Tamsin Greig gender-swapped 2017): chilling authoritarian who gets exactly what he deserves Shakespeare deliberately wrote him so all three readings are possible.

Feste – The wise fool who sees everything He is on stage far more than most realise (more lines than Orsino). Directorial tip: the moment he stops smiling is the moment the audience realises the comedy has a dark underside.

Historical & Literary Context Every Reader Should Know

- Twelfth Night was named after the final night of Christmas revels (January 6) when social hierarchy was inverted — servants became lords for a day. The play is literally structured as one long Lord of Misrule festival.

- Illyria is not a real place with coherent geography; it is Shakespeare’s dream-Mediterranean where anything can happen.

- Direct links to earlier plays: the shipwrecked twin plot from Comedy of Errors, the cross-dressed heroine from As You Like It, the gulling of a steward from The Taming of the Shrew.

Study & Exam Toolkit

Top 10 Most Frequently Quoted/Examined Lines (with quick annotations)

- “If music be the food of love…” – excess in love

- “Make me a willow cabin…” – persuasive rhetoric

- “Some are born great…” – self-deception

- “I am not what I am” – identity 5 “She sat like Patience on a monument” – concealed suffering

- “O time, thou must untangle this” – comic structure

- “Many a good hanging prevents a bad marriage” – bawdy humour

- “I’ll be revenged on the whole pack of you” – problem-play ending

- “The rain it raineth every day” – bittersweet closure

- “What You Will” – interpretive freedom

Sample A-Level / AP / IB Essay Questions & Model Thesis Statements Q: Is Twelfth Night a celebration or a critique of romantic love? Thesis: Shakespeare celebrates love’s transformative joy while simultaneously exposing its capacity for narcissism, cruelty, and self-deception.

Q: To what extent is Malvolio a tragic rather than comic figure? Thesis: Although presented within a comic framework, Malvolio’s systematic humiliation and unredeemed exit align him more closely with Shakespearian tragic outsiders than with the reconciled blocking figures of pure comedy.

Further Reading & Trusted Editions

Best modern editions:

- Arden Shakespeare (Third Series) – Keir Elam (gold standard footnotes)

- Oxford Shakespeare – Roger Warren & Stanley Wells

- Folger Shakespeare Library – Barbara Mowat & Paul Werstine (student-friendly facing-page notes)

- New Cambridge – Elizabeth Story Donno

Best filmed/staged versions:

- Trevor Nunn 1996 (cinematic, with Imogen Stubbs & Helena Bonham Carter)

- Globe 2012 (all-male Original Practices with Mark Rylance & Stephen Fry)

- National Theatre 2017 (gender-swapped Malvolio – Tamsin Greig)

Why Twelfth Night Still Matters in 2025

Four hundred years after it was written, Twelfth Night remains Shakespeare’s most modern comedy because it refuses to give us the tidy resolutions we crave. Love is shown to be chaotic, identity fluid, and laughter often cruel. Yet the play never becomes cynical — Viola’s courage, Sebastian’s wonder, and even Feste’s melancholy wisdom remind us that human beings are capable of astonishing transformation when fortune finally smiles. This scene-by-scene, line-by-line annotated guide is designed to stay open beside your text whether you are a first-time reader or a lifelong scholar. Bookmark it, share it, come back to it every time you revisit Illyria. Because, as the subtitle invites us — this play can be whatever you will.