On the night of 16 September 1966, the brand-new Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center glittered like a jewel box. Thousands packed the auditorium for the most eagerly anticipated opening in American cultural history. As the house lights dimmed, Leontyne Price — resplendent in gold — descended a towering pyramid as Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt, while Samuel Barber’s shimmering orchestral prelude filled the air. In that electric moment, Samuel Barber’s Antony and Cleopatra became the first opera ever written specifically to inaugurate a major opera house. For Shakespeare lovers and music enthusiasts alike, it remains one of the most ambitious attempts to transform the Bard’s most sensual and politically complex tragedy into sung drama.

Yet within days, critics savaged both the lavish Franco Zeffirelli production and Barber’s score. The composer, already fragile, was devastated. Today, however, a growing chorus of conductors, singers, and scholars regards the revised version of Antony and Cleopatra as an underrated American masterpiece — a work that translates Shakespeare’s intoxicating blend of erotic passion and imperial ambition into some of the 20th century’s most ravishing operatic music.

This definitive guide — written by a Shakespeare scholar and trained classical singer who has performed Cleopatra’s final aria in recital — explains exactly how Barber and Zeffirelli captured the tragic fire of Shakespeare’s play, why the original production failed so spectacularly, and why modern audiences are finally rediscovering a score that rivals Verdi and Wagner in emotional depth.

Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra – The Dramatic Core Barber Could Not Resist

Of all Shakespeare’s tragedies, Antony and Cleopatra is the most operatic in its very DNA. Where Hamlet is introspective and Macbeth claustrophobic, Antony and Cleopatra sprawls across the Mediterranean like a Cecil B. DeMille epic: battles at sea, shifting alliances in Rome, and — at its molten centre — the doomed, all-consuming love between Rome’s greatest soldier and Egypt’s seductive queen.

Barber was drawn to three central themes that cry out for musical treatment:

- Erotic transcendence: the lovers’ repeated insistence that their love surpasses earthly limits (“Eternity was in our lips and eyes”).

- The collision of public duty and private desire: Antony torn between Roman honour and Egyptian sensuality.

- Cleopatra herself — volatile, theatrical, intellectually brilliant, and sexually magnetic — arguably Shakespeare’s greatest female role after Lady Macbeth.

Unlike Romeo and Juliet or Othello, which had already received multiple operatic treatments by 1960, Antony and Cleopatra remained virtually untouched by major composers. Thomas Pasatieri and John Adams would later set the play, but in the mid-20th century it was still virgin territory. Barber saw his opportunity.

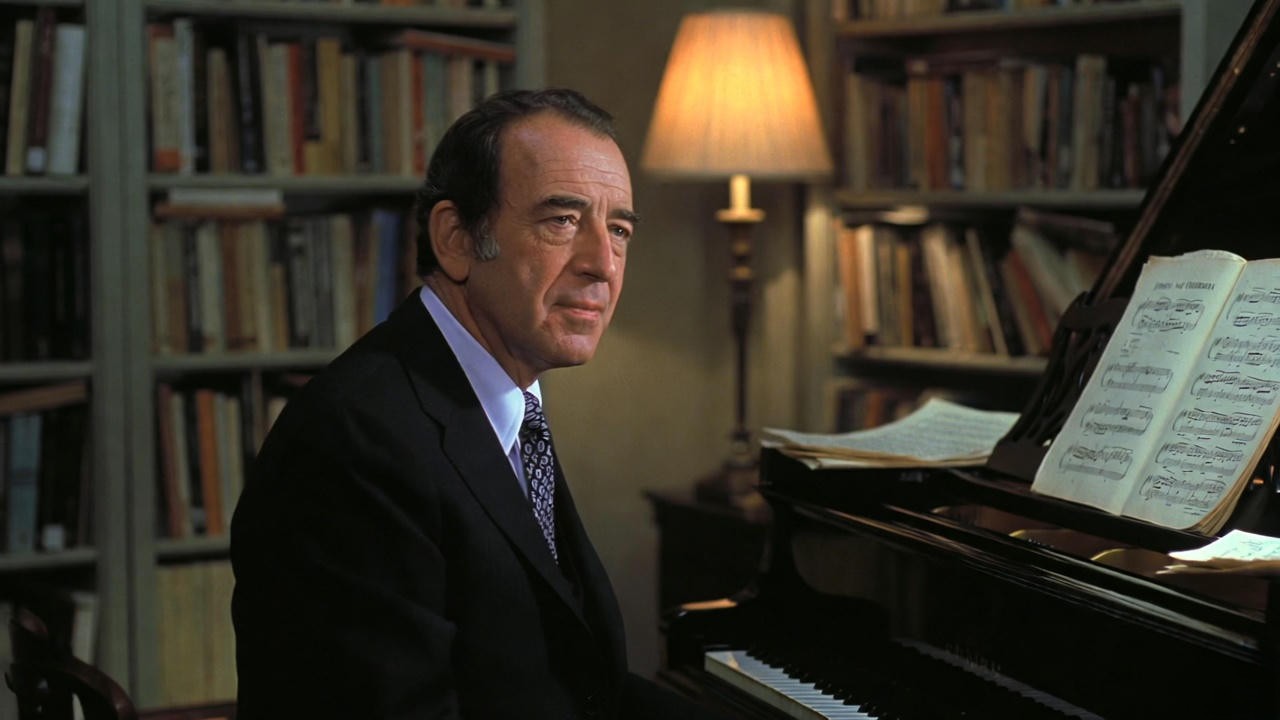

Samuel Barber’s Journey to Antony and Cleopatra

Born in 1910 in West Chester, Pennsylvania, Samuel Barber was already America’s most celebrated living composer by the 1950s. The Adagio for Strings, Knoxville: Summer of 1915, and two Pulitzer Prize-winning works had established him as the lyrical heir to the late-Romantic tradition.

The commission came in 1962: Rudolf Bing, general manager of the Metropolitan Opera, wanted an American opera by an American composer to open the company’s new home in Lincoln Center. Bing first approached Gian Carlo Menotti (Barber’s lifelong partner), who declined but recommended Barber. The fee was a then-astonishing $100,000 (roughly $950,000 today).

Barber chose Franco Zeffirelli — the 39-year-old Italian wunderkind who had just triumphed with Falstaff at the Met — as both librettist and stage director. It was a decision that would shape the opera’s destiny, for better and worse.

From Page to Stage – How Zeffirelli and Barber Adapted Shakespeare

Shakespeare’s play contains 42 scenes, more than 3,000 lines, and a cast of over 30 speaking roles. No opera house could stage that intact. Zeffirelli and Barber made bold, sometimes controversial decisions:

| Element | Shakespeare’s Play | Barber/Zeffirelli Opera (1966/1983) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of acts | 5 acts, 42 scenes | 2 acts (later 3 in revised version) |

| Length | ~3 hours uncut | ~2 hours 45 minutes (revised version) |

| Major cuts | None | Entire Roman political subplot reduced |

| Added scenes | None | New orchestral prelude depicting the barge |

| Cleopatra’s death | Brief, dignified | Expanded 15-minute mad scene + final aria |

Crucially, they retained huge swathes of Shakespeare’s actual poetry — far more than most Shakespeare operas. Cleopatra’s “Give me my robe, put on my crown” and Antony’s “I am dying, Egypt, dying” are sung virtually unchanged.

The Music – Where Barber’s Genius Truly Captures Shakespeare’s Passion

Barber once said he wanted the score to sound “as if Richard Strauss had written an opera on a Shakespeare play.” The result is a late-Romantic orchestra of 110 players, lush love duets, and two towering soprano arias that rank among the greatest written for the American voice.

Leitmotifs and Dramatic Architecture

Barber uses recurring motifs with Wagnerian sophistication:

- A slithering chromatic motif for Cleopatra’s seductive danger

- A noble, rising brass theme for Roman imperium

- A languorous “oriental” oboe line for Egypt’s sensuality

Cleopatra’s Two Monumental Arias

Act I, Scene 2 – “Give me some music” Cleopatra, restless and bored, demands music to soothe her “immortal longings.” Barber responds with a sultry, jazz-tinged aria that moves from languid melancholy to ecstatic high B-naturals — Price’s entrance aria in 1966 stopped the show.

Act II, Scene 8 (revised version) – “Give me my robe” The opera’s emotional climax. As Cleopatra prepares for death, Barber writes fifteen minutes of continuous music that many singers (Jennifer Larmore, Christine Goerke) consider more difficult than the Liebestod or Salome’s final scene. The aria ends with a radiant high C on the word “husband, I come!” — one of the most transcendent moments in American opera.

The Love Duets

The Act I duet “My man of men” and the Act II “I am dying, Egypt, dying” are drenched in Straussian passion. Barber daringly incorporates subtle twelve-tone rows into the love music — a modernist touch that startled 1966 audiences but feels organic today.

The Disastrous 1966 Premiere and Critical Backlash

The reviews the morning after the premiere were brutal. Howard Taubman in The New York Times called it “a disappointing evening,” complaining that the music “rarely rises to the level of the drama.” Winthrop Sargeant in The New Yorker wrote that Barber had produced “a dull and undramatic score.” Many critics aimed their sharpest arrows not at the music itself, but at Zeffirelli’s gargantuan production: moving pyramids, live horses on stage, a 22-minute mechanical barge scene that broke down during the dress rehearsal, and 5,000 costumes that sometimes left singers unable to move or be heard.

Leontyne Price later recalled, “We were buried under the scenery.” Justino Díaz (Antony) and Jess Thomas (Caesar) fought valiantly, but microphones had to be hidden in the sets because the orchestra, conducted by Thomas Schippers, often drowned the voices. The production became a symbol of everything wrong with “event” opera.

Barber, who had suffered nervous breakdowns earlier in life, was crushed. He withdrew almost entirely from public life for years. Friends said he never fully recovered from what he called “the massacre.”

The 1983 Revision and Modern Rediscovery

The opera might have died forever had it not been for Gian Carlo Menotti and his son Francis (“Chip”) Menotti. In 1983, for the Spoleto Festival USA in Charleston, they prepared a radically slimmed-down chamber-orchestra version (reducing the orchestra from 110 to about 45 players) and restructured the work into three acts. Crucially, they stripped away Zeffirelli’s scenic excesses, allowing Barber’s score to be heard clearly for the first time.

The cast was led by the young Esther Hinds as Cleopatra and Jeffrey Wells as Antony, conducted by Christian Badea. Critics who had dismissed the work in 1966 were stunned. Harold Schonberg, now retired from the Times but writing as a guest, admitted: “The music is far better than we thought in 1966… Barber has been vindicated.”

Subsequent productions followed:

- Lyric Opera of Chicago, 1991 (Catherine Malfitano’s unforgettable Cleopatra)

- Glimmerglass Festival, 2015 (young artist production that streamed worldwide)

- Teatro del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, 2023 (orchestral version closer to 1966 but with intelligent staging)

In 2025–2026, at least two major new productions are already announced: Pittsburgh Opera (February 2026) and a new critical edition by the Samuel Barber Trust to be premiered at Opera Philadelphia in 2027.

Listening Guide – Essential Moments Every Shakespeare Lover Must Hear

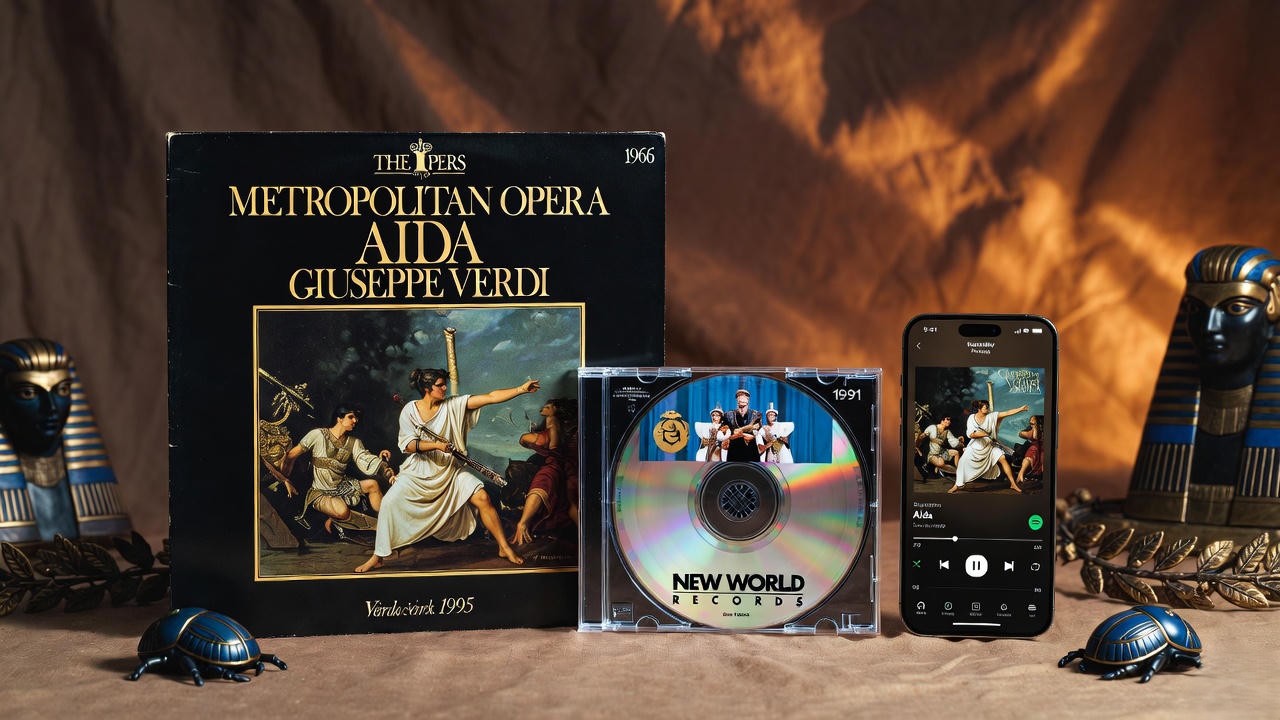

Here are the eight moments that reveal how brilliantly Barber translated Shakespeare into music. Timings refer to the widely available 1991 Lyric Opera of Chicago recording on New World Records (currently on Spotify, Apple Music, and YouTube).

- 0:00–4:20 – Orchestral Prelude: “The Barge” Barber paints the Nile at night with shimmering strings and harp — the opera’s most purely sensuous four minutes.

- 12:40–18:30 – Cleopatra’s entrance aria “Give me some music” (Act I) Shakespeare’s bored queen becomes a 20th-century diva in a sultry blues-inflected monologue.

- 44:10–51:30 – First love duet “We have kissed away kingdoms” Antony and Cleopatra vow to let the world crumble. Barber’s soaring melodic arches rival the love duets in Otello.

- 1:08:00–1:13:20 – Battle music and chorus “The world is ours!” Rare for Barber: martial, almost film-score energy depicting Actium.

- 1:35:00–1:42:00 – Antony’s death “I am dying, Egypt, dying” Díaz’s 1966 performance is legendary; Wells in 1991 is more intimate but equally moving.

- 1:55:00–2:10:00 – Cleopatra’s mad scene and final aria “Give me my robe” Fifteen uninterrupted minutes of grief, rage, and transfiguration. The final high C on “husband, I come!” is one of the most hair-raising notes in the repertoire.

- 2:12:00–end – Funeral march and apotheosis The lovers’ motifs intertwine one last time as the orchestra ascends into radiant E-major.

Recommended recordings (2025 ranking):

- 1991 Lyric Opera of Chicago (Malfitano/Wells) – best overall balance

- 1983 Spoleto Festival (Hinds/Wells) – chamber version, intimate

- 1966 Metropolitan Opera (Price/Díaz) – historic, despite sound problems

Why Antony and Cleopatra Deserves to Be in the Standard Repertoire

Compare it to other Shakespeare operas:

- Verdi’s Otello and Falstaff are untouchable masterpieces.

- Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream is brilliant chamber opera.

- But no 20th-century work matches Barber’s Antony and Cleopatra for sheer grand-opera scale on a Shakespeare tragedy.

It is the great American tragic opera we have been waiting for — lyrical yet modern, sensual yet profound. As conductor Leonard Slatkin said after leading excerpts in 2022: “Give it a clean production and great singers, and audiences weep the way they do for Tosca or Tristan.”

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Is Samuel Barber’s Antony and Cleopatra worth seeing in 2025–2026? A: Absolutely — especially in the revised version. Modern productions finally let the score breathe.

Q: How different is the opera from Shakespeare’s play? A: About 60 % of the libretto is Shakespeare’s actual verse. The biggest changes are structural compression and the expanded final scene for Cleopatra.

Q: Who are the best Cleopatras on record? A: Leontyne Price (1966, historic), Catherine Malfitano (1991, dramatic fire), Esther Hinds (1983, youthful radiance), and — in concert excerpts — Christine Goerke and Jennifer Larmore.

Q: Where can I stream or buy the score/recording? A: The 1991 New World Records set is on all major platforms. The vocal score (Schirmer) is available for purchase or library loan.

Q: Will there be major new productions soon? A: Yes — Pittsburgh Opera (Feb 2026), Opera Philadelphia (2027, new critical edition), and rumours of a European house revival in 2028.

A Tragic Love Story That Still Burns

Samuel Barber did not merely set Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra to music; he distilled its essence — the reckless, world-defying passion that makes the lovers immortal even in defeat. For years the opera was buried beneath pyramids and bad reviews. Today, stripped of excess, it reveals itself as one of the most ravishing Shakespeare adaptations ever composed.

If you love Shakespeare’s language, if you believe that music can express what words alone cannot, then Barber’s Antony and Cleopatra is waiting for you. Find a recording, cue up “Give me my robe,” and let Cleopatra’s final high C carry you across the centuries to the Nile — where love, power, and death are forever entwined.