Have you ever argued with someone who refused to see things from any angle but their own? Or felt the frustration of personal beliefs clashing with undeniable facts? At the heart of such moments lies a fundamental linguistic and philosophical tension: the search for an antonym for point of view. While dictionaries often suggest “objectivity,” “fact,” or “impartiality,” the concept runs far deeper—especially in literature. Few writers have explored this contrast more masterfully than William Shakespeare, whose plays constantly pit subjective perspective (personal bias, emotion, and interpretation) against objective reality (impartial truth revealed through action, irony, and dramatic structure). In this comprehensive analysis, we will uncover how Shakespeare transforms a simple linguistic opposition into profound insight into human nature.

For students, educators, theater enthusiasts, and lifelong learners seeking deeper Shakespearean understanding, recognizing this dynamic unlocks richer interpretations of his timeless works. This article examines the antonym for point of view through Shakespeare’s dramatic techniques, offering detailed play-by-play analysis, scholarly context, and practical reading strategies you won’t find in standard summaries.

Understanding “Point of View” and Its Antonyms

Defining Point of View in Language and Literature

In everyday usage, “point of view” refers to an individual’s attitude, opinion, or standpoint on an issue. Linguistically, it derives from the French point de vue—literally “point from which one views.” In literary theory, the term expands to encompass narrative perspective: first-person (deeply subjective), third-person limited (partially subjective), or third-person omniscient (closer to objective).

Shakespeare, writing primarily for the stage rather than the page, operated in an inherently dramatic medium that presents events objectively—actors perform actions visible to all—while simultaneously granting access to characters’ inner subjectivity through soliloquies and asides.

Common Antonyms for “Point of View”

Standard thesauri list several candidates:

- Objectivity – detachment from personal feelings or bias

- Fact or reality – as opposed to opinion or interpretation

- Impartiality or neutrality – absence of favoritism

- Universality – a truth that transcends individual experience

No single word serves as a perfect antonym because “point of view” operates on multiple levels: spatial, attitudinal, and narrative. The most useful conceptual opposite, particularly in dramatic context, is objective reality—the impartial truth that exists independently of any character’s perception.

Why This Matters in Shakespeare Studies

Shakespeare’s genius lies in exploiting this tension. His plays rarely rely on a single narrator’s limited perspective (as novels often do). Instead, the audience occupies a privileged, near-omniscient position, witnessing events and motives that individual characters cannot. This structural objectivity constantly undercuts subjective delusion, producing tragic irony and profound philosophical resonance.

Renowned Shakespearean scholar A.C. Bradley noted in Shakespearean Tragedy (1904) that the playwright’s tragedies derive much of their power from the discrepancy between what characters believe and what the audience knows to be true. Northrop Frye later described Shakespeare’s dramatic world as one where “the audience sees the whole action, while the characters see only part of it.”

Subjective vs. Objective Perspective: Core Concepts in Drama

Subjective Perspective Explained

Subjective perspective manifests through characters’ expressed thoughts, emotions, and biased interpretations. Shakespeare’s primary tools for conveying subjectivity are:

- Soliloquies – extended speeches delivered when a character is alone onstage

- Asides – brief comments directed to the audience

- Private dialogues – conversations that reveal hidden motives

These devices immerse the audience in a character’s inner world, often clouded by passion, ambition, madness, or deception.

Objective Reality as the Antonym

Objective reality emerges from the play’s overall action—what actually happens, independent of any character’s interpretation. The audience, seeing the full stage picture, becomes the arbiter of truth. Dramatic techniques that reinforce objectivity include:

- Dramatic irony – when the audience knows more than the characters

- Multiple conflicting viewpoints – no single perspective dominates

- Visible action – deeds that contradict spoken claims

Shakespeare’s Mastery of the Contrast

Unlike novelists who can restrict knowledge to one character’s consciousness, Shakespeare’s stage demands visibility. Yet he brilliantly layers subjective illusion atop objective fact, creating tension that mirrors real human experience. As Harold Bloom observed in Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human (1998), “We are all Hamlet-like in our subjectivity, yet the world proceeds with an objectivity indifferent to our desires.”

Hamlet: The Pinnacle of Subjective Turmoil vs. Objective Truth

Few works illustrate the antonym for point of view more vividly than Hamlet.

Hamlet’s Subjective Point of View

Prince Hamlet’s soliloquies provide unparalleled access to a tormented psyche. His famous “To be, or not to be” speech (Act 3, Scene 1) reveals existential despair, fear of the afterlife, and paralyzing introspection:

“Thus conscience does make cowards of us all, And thus the native hue of resolution Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought…”

Here, subjectivity reigns—Hamlet’s hesitation stems from overthinking and moral scruple. We also witness potential madness (feigned or genuine), further clouding reliable perception.

Contrasting Objective Reality

The audience, however, possesses knowledge Hamlet lacks or doubts:

- We see the Ghost and hear its command (Act 1, Scene 5)

- We witness Claudius’s guilty prayer (Act 3, Scene 3)

- We observe the play-within-a-play (“The Mousetrap”) objectively proving Claudius’s guilt

This dramatic irony positions objective reality as the clear antonym to Hamlet’s subjective uncertainty. The prince’s delayed action arises precisely from his entrapment in personal perspective, while the audience grasps the broader truth.

Key Examples and Analysis

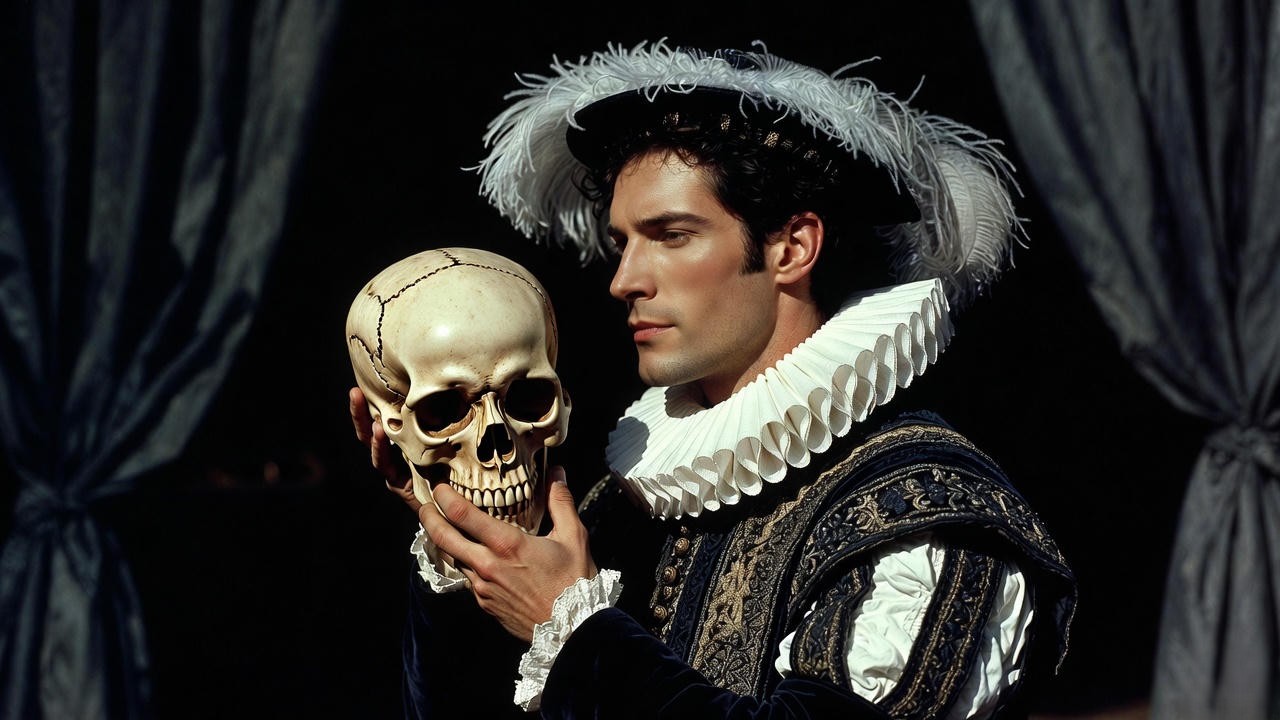

The graveyard scene (Act 5, Scene 1) further highlights the contrast. Hamlet’s philosophical musings on Yorick’s skull represent peak subjectivity (“Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him, Horatio…”). Moments later, objective reality intrudes violently with Ophelia’s funeral procession and Laertes’ grief, forcing confrontation with consequences.

Scholar Jan Kott, in Shakespeare Our Contemporary (1964), argued that Hamlet remains eternally modern because it dramatizes the perpetual conflict between individual perception and indifferent reality—a conflict we recognize in today’s polarized discourse.

Macbeth: Descent from Subjective Ambition to Objective Consequences

Macbeth traces a similar trajectory, beginning in subjective delusion and culminating in crushing objective retribution.

Early Subjectivity in Macbeth and Lady Macbeth

The play opens with the witches’ prophecy igniting Macbeth’s latent ambition. His aside in Act 1, Scene 3 reveals the birth of treacherous thought:

“Why do I yield to that suggestion Whose horrid image doth unfix my hair…”

The hallucinatory dagger soliloquy (Act 2, Scene 1) plunges us deeper into subjective distortion: “Is this a dagger which I see before me…?” Lady Macbeth’s unsexing invocation further exemplifies willful rejection of natural empathy in favor of ruthless personal vision.

Shift to Objective Horror

As the play progresses, focus shifts from private ambition to public consequences. The murder of Duncan occurs offstage, but its aftermath dominates: Banquo’s ghost at the banquet (seen only by Macbeth) underscores subjective guilt, while the audience observes objective political fallout.

The slaughter of Macduff’s family (Act 4, Scene 2) is presented with heartbreaking objectivity—innocent victims given voice before their deaths. This scene counterbalances Macbeth’s increasingly isolated perspective.

Thematic Insights

By the end, Macbeth recognizes the hollowness of his subjective interpretation of the prophecies. His nihilistic “Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow” soliloquy (Act 5, Scene 5) acknowledges objective reality’s triumph:

“Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player That struts and frets his hour upon the stage…”

Critics such as L.C. Knights have noted how Shakespeare uses this progression to explore moral causality: subjective ambition inevitably collides with objective moral order.

Additional Plays Illustrating the Contrast

Shakespeare’s exploration of subjective perspective versus objective reality extends far beyond the major tragedies. Several other plays employ this dynamic to varying degrees, enriching his canon with multifaceted insights into human perception.

Romeo and Juliet: Youthful Subjectivity vs. Societal Objectivity

Romo and Juliet (c. 1597) presents one of Shakespeare’s most poignant clashes between passionate individual viewpoint and the indifferent reality of social structures.

The young lovers inhabit a world of intense subjectivity. Romeo’s infatuation shifts overnight from Rosaline to Juliet, exemplified in his hyperbolic language: “Did my heart love till now? Forswear it, sight! / For I ne’er saw true beauty till this night” (Act 1, Scene 5). Juliet similarly embraces impulsive devotion, declaring “My bounty is as boundless as the sea, / My love as deep” (Act 2, Scene 2).

Yet the audience witnesses the objective reality that dooms them: the ancient grudge between Montagues and Capulets, reinforced by Prince Escalus’s decrees and the fatal chain of misunderstandings (the delayed letter, the apothecary, the tomb scene). Dramatic irony abounds—viewers know Friar Laurence’s plan has failed long before the lovers do.

This contrast underscores Shakespeare’s commentary on how youthful subjectivity, while beautiful, often proves tragically incompatible with societal objectivity. As critic Jill L. Levenson notes in the Oxford Shakespeare edition, the play’s prologue establishes an omniscient frame that renders the lovers’ private passion both moving and inevitably futile.

The Tempest: Prospero’s Controlling Subjectivity vs. Island’s Objective Magic

In his late romance The Tempest (c. 1611), Shakespeare flips the dynamic: Prospero imposes his subjective will through magic, yet the island’s natural order ultimately asserts objective limits.

Prospero’s perspective dominates early acts. His narrative to Miranda (Act 1, Scene 2) frames events through personal grievance—“I have done nothing but in care of thee”—while his manipulation of Ariel and Caliban reveals authoritarian bias. Even the storm is his subjective creation.

However, objective reality gradually reasserts itself. Caliban’s earthy counter-perspective (“This island’s mine, by Sycorax my mother”) challenges Prospero’s colonial narrative. The young lovers Miranda and Ferdinand experience genuine, unmanipulated emotion, and Gonzalo’s utopian vision offers an alternative impartial idealism.

By Act 5, Prospero acknowledges objective moral reality: “The rarer action is / In virtue than in vengeance” (Act 5, Scene 1). His abjuration of magic signifies surrender of subjective control to broader human truths. Stephen Orgel’s Arden edition highlights how the play’s metatheatrical elements reinforce audience omniscience, making Prospero’s eventual humility inevitable.

Othello: Iago’s Manipulated Subjectivity vs. Tragic Objective Truth

Othello (c. 1603) masterfully demonstrates how malicious manipulation can distort subjectivity until it destroys contact with objective reality.

Othello begins with confidence rooted in military achievement, but Iago’s insinuations systematically erode this. The handkerchief—objective evidence planted by Iago—becomes “proof” only through Othello’s increasingly subjective jealousy: “Trifles light as air / Are to the jealous confirmations strong / As proofs of holy writ” (Act 3, Scene 3).

Iago himself operates from pure subjective malice (“I hate the Moor”), never fully explained, while the audience sees his machinations objectively. Desdemona’s innocence and Cassio’s loyalty remain clear to viewers throughout.

The play’s devastating power stems from this gap: Othello murders based on distorted perception, only recognizing objective truth too late—“O fool! fool! fool!” (Act 5, Scene 2). Scholar Edward Pechter argues that Othello uniquely makes the audience complicit in watching subjectivity override reality, mirroring real-world vulnerabilities to misinformation.

Comparative Overview: Subjective and Objective Elements Across Key Plays

To visualize Shakespeare’s consistent use of this contrast, consider the following table:

| Play | Primary Subjective Tool | Key Objective Mechanism | Central Tension Resolved By |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hamlet | Soliloquies, feigned madness | Dramatic irony, play-within-play | Delayed recognition of Claudius’s guilt |

| Macbeth | Asides, hallucinations | Visible consequences (murders) | Moral order reasserting itself |

| Romeo and Juliet | Impulsive declarations | Prologue and societal feud | Tragic misunderstanding |

| Othello | Jealous monologues | Planted evidence, honest characters | Late revelation of truth |

| The Tempest | Prospero’s narratives | Natural magic, counter-perspectives | Voluntary renunciation of power |

This pattern reveals Shakespeare’s deliberate technique: subjective immersion draws empathy, while objective detachment provokes judgment.

Broader Implications in Shakespeare’s Canon

Multiple Perspectives and Dramatic Irony

Across his works, Shakespeare rarely privileges a single point of view. Even in histories like Henry IV, Falstaff’s comic subjectivity contrasts with Prince Hal’s calculating objectivity, and Hotspur’s honor-bound perspective clashes with political reality.

This multiplicity anticipates modern concepts of relativism while grounding drama in observable action. As Frank Kermode observed in Shakespeare’s Language (2000), the playwright’s refusal of narrative omniscience within characters forces audiences to synthesize truth themselves—an active, objective engagement.

Influence on Modern Literature and Theater

Shakespeare’s subjective-objective dialectic profoundly shaped subsequent writers:

- Novelists like Henry James and Virginia Woolf adapted limited perspective to explore subjectivity

- Modern playwrights (Brecht, Pirandello) built on his metatheatrical objectivity

- Contemporary adaptations (e.g., Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet, Akira Kurosawa’s Ran) often heighten visual objectivity to comment on subjective delusion

Lessons for Readers Today

Understanding this antonym for point of view equips modern readers to navigate information overload. In an era of echo chambers and “alternative facts,” Shakespeare reminds us to seek dramatic irony’s broader view—questioning personal bias against verifiable reality.

Practical application: When consuming news or social media, ask, “What might the audience (history, evidence) know that individual sources do not?”

Expert Insights and Tips for Deeper Appreciation

Scholarly Views on Shakespeare’s Technique

Leading critics agree on the centrality of this contrast:

- A.C. Bradley: Emphasized tragic irony arising from character ignorance

- Northrop Frye: Saw Shakespeare’s comedies resolving subjectivity into social objectivity

- Janet Adelman: Explored maternal subjectivity versus patriarchal reality in tragedies

- Patricia Parker: Analyzed how language itself creates subjective distortion

Reading/Teaching Tips

- Track soliloquies vs. action – Note where character claims diverge from observed events

- Map dramatic irony – List what each character knows versus audience knowledge

- Compare editions – Folger Shakespeare Library for accessible notes; Arden for scholarly depth

- Performance viewing – Watch multiple productions (e.g., RSC, Globe) to see how directors emphasize objectivity through staging

Common Misinterpretations to Avoid

- Assuming soliloquies reveal absolute truth (they reflect subjective states)

- Reducing plays to single character perspectives (ignore ensemble objectivity)

- Projecting modern psychological realism onto Elizabethan dramatic conventions

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the best antonym for “point of view”? Context determines the strongest opposite. Linguistically, “objectivity” or “impartiality” works best; in dramatic terms, “objective reality” captures Shakespeare’s structural approach.

How does Shakespeare use soliloquies to show subjectivity? Soliloquies grant direct access to unfiltered thoughts, often revealing bias, rationalization, or delusion unavailable to other characters.

Is Hamlet’s perspective reliable? No—his soliloquies show genuine turmoil, but dramatic irony reveals knowledge gaps and potential exaggeration.

Why is objective reality harder to portray in drama than novels? Stage action is inherently visible and shared; playwrights must work harder to restrict audience knowledge compared to novelists’ narrative control.

Can this subjective-objective contrast help understand modern media bias? Absolutely. Recognizing when sources present limited perspectives versus verifiable events mirrors Shakespearean dramatic irony.

Which Shakespeare play best illustrates balanced perspectives? Twelfth Night—multiple disguises create layered subjectivity, resolved through objective revelation in the final scene.

Are there comedies where objectivity triumphs more gently? Yes—As You Like It and A Midsummer Night’s Dream use forest settings to temporarily heighten subjectivity, then restore social objectivity harmoniously.

How did Shakespeare’s theater conditions influence this technique? Open staging and minimal sets forced reliance on language for subjectivity and action for objectivity.

The search for an antonym for point of view leads us inevitably to Shakespeare’s profound dramatic achievement: placing subjective human experience under the unflinching light of objective reality. From Hamlet’s tortured introspection to Prospero’s humbled recognition, his plays dramatize the eternal tension between personal perception and impartial truth.

This contrast not only powers his tragedies and romances but offers timeless wisdom: genuine understanding requires stepping beyond individual standpoint to embrace broader reality. Next time you revisit a Shakespeare play, watch for these moments of revelation—when character delusion meets dramatic fact—and you’ll discover layers of meaning previously hidden.

Which play will you reread with this lens? Share your insights in the comments below, and let’s continue exploring the endless depths of Shakespeare’s genius together.