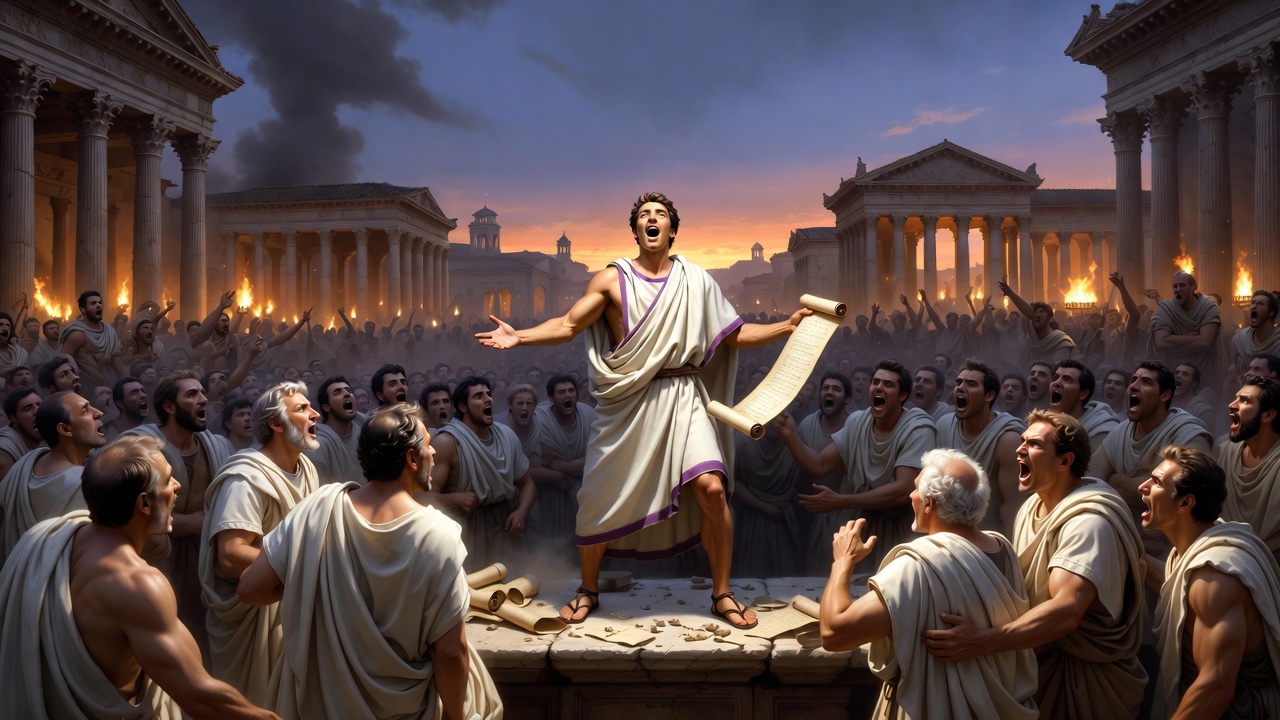

In 32 BC, a single document reportedly shaken open in the Roman Forum changed the course of Western history.

Octavian — the young, calculating heir of Julius Caesar — stood before the assembled senators and people and read what he claimed was Mark Antony’s last will and testament. According to Octavian’s presentation, Antony had declared his wish to be buried not in Rome, but in Alexandria beside Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt. He had allegedly promised vast Roman territories to Cleopatra’s children and — most explosively — intended to transfer the seat of Roman power to the Egyptian capital.

The reaction was immediate and visceral. Shock turned to outrage. Romans who had tolerated Antony’s Eastern lifestyle could no longer ignore the narrative Octavian was carefully crafting: Antony was no longer a Roman leader. He had become the tool of a foreign queen who dreamed of ruling over Rome itself.

Why did Octavian not trust Antony and Cleopatra to rule? The question cuts to the heart of one of the most consequential power struggles in ancient history — a struggle that ended the Roman Republic and gave birth to the Roman Empire under Augustus.

The answer is not simple romantic jealousy or mere personal animosity. It was a lethal combination of legitimate strategic fears, dynastic rivalry, cultural prejudice, and one of the most effective propaganda campaigns in antiquity. Octavian understood that if Antony and Cleopatra were allowed to consolidate their power in the East, his own claim to lead Rome — and the very idea of Roman supremacy — would be permanently undermined.

This same collision between political necessity and overwhelming passion would later fascinate William Shakespeare. In his tragedy Antony and Cleopatra, the historical distrust is transformed into a timeless meditation on love, duty, empire, and self-destruction. Yet Shakespeare’s drama rests on real events — events shaped by Octavian’s refusal to accept Antony and Cleopatra as legitimate co-rulers of the Roman world.

In this in-depth article we will examine:

- The fragile political alliances that first created distrust

- The existential threat posed by Caesarion

- Antony’s Eastern empire and Cleopatra’s resources

- Deep-seated Roman cultural fears

- Octavian’s brilliant use of propaganda

- How Shakespeare reimagines these historical fears

- The decisive campaign that ended in Actium

- The long-term consequences for Rome and the Western world

By the end, you will understand not only why Octavian refused to trust Antony and Cleopatra to rule, but why that refusal was — from his perspective — the only rational choice if Rome was to survive in its traditional form.

Historical Context — The Fragile Second Triumvirate and the Seeds of Distrust

Aftermath of Julius Caesar’s Assassination (44 BC)

When Julius Caesar was murdered on the Ides of March 44 BC, the Roman world fractured.

Two men quickly emerged as the most powerful claimants to Caesar’s legacy:

- Mark Antony, Caesar’s loyal consul, experienced general, and charismatic popular leader

- Gaius Octavius (later Octavian), Caesar’s 18-year-old grandnephew, whom Caesar had quietly adopted and named as his primary heir in his will

Antony controlled the veteran legions and the political machinery in Rome. Octavian had only a name — but it was the most powerful name in the Roman world: Caesar.

In November 43 BC, Antony, Octavian, and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus formed the Second Triumvirate — officially to “restore the Republic,” in reality to eliminate their enemies and divide the Roman world among themselves. Proscriptions followed: thousands of senators and equestrians were murdered, their property confiscated. Cicero’s head and hands were displayed in the Forum.

From the beginning, the alliance was uneasy. Octavian and Antony were never friends. They were rival heirs to Caesar’s legacy.

The uneasy alliance and early flashpoints (43–36 BC)

Between 43 and 36 BC several events deepened the mistrust:

- The Perusine War (41–40 BC) — Antony’s brother Lucius and his wife Fulvia raised an army in Italy against Octavian while Antony was in the East. Octavian crushed the rebellion and starved Perusia (modern Perugia) into surrender. Although Antony denied responsibility, Octavian never fully believed him.

- Marriage to Octavia (40 BC) — To seal reconciliation, Antony married Octavian’s sister Octavia — a political match that produced two daughters.

- Treaty of Tarentum (37 BC) — Antony promised 120 ships to help Octavian against Sextus Pompey. In return Octavian was to supply troops for Antony’s Parthian campaign. Antony sent the ships; Octavian never sent the promised legions.

By the late 30s BC, Antony was spending almost all his time in the Greek East, increasingly identifying with Hellenistic kingship rather than Roman magistracy.

Cleopatra enters the equation — from Caesar’s lover to Antony’s partner

Cleopatra VII had already been a major player in Roman politics since 48 BC, when she allied with Julius Caesar and bore him a son — Ptolemy XV Caesar, known as Caesarion.

After Caesar’s death she returned to Egypt. In 41 BC she met Antony in Tarsus. Their relationship quickly became both personal and political. Cleopatra provided money, grain, ships, and political legitimacy in the East; Antony provided military protection and recognition of her son’s status.

The birth of three more children (Alexander Helios, Cleopatra Selene, Ptolemy Philadelphus) and the public ceremonies that followed would soon make Octavian’s position dangerously vulnerable.

Reason #1 — Caesarion: The Living Threat to Octavian’s Legitimacy

Octavian’s entire claim to power rested on one legal and symbolic fact: he was Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus — the adopted son and heir of the deified Julius Caesar.

As long as Caesarion — a biological son acknowledged by Caesar in Egypt — lived, Octavian’s claim was contestable.

In 34 BC Antony staged the famous Donations of Alexandria. In a grand public ceremony he:

- Declared Cleopatra “Queen of Kings”

- Proclaimed Caesarion “King of Kings” and co-ruler with his mother

- Recognized Caesarion publicly as Julius Caesar’s legitimate son

- Distributed Roman client kingdoms and territories to Cleopatra and the three children she had with Antony

For Octavian this was intolerable.

Caesarion was approximately 13 years old in 34 BC — old enough to be presented as a future leader of the Caesarian faction. If Antony and Cleopatra won, they could rally the eastern legions, the Greek cities, and the surviving Caesarian loyalists under the banner of Caesar’s true blood heir.

Octavian’s propaganda would later call Caesarion “the false Caesar” — but privately he understood the danger. Ancient sources (Plutarch, Cassius Dio, Suetonius) all agree that Octavian regarded Caesarion as the single greatest long-term threat to his position.

Reason #2 — Antony’s Eastern Empire and Cleopatra’s Vast Resources

By the late 30s BC Antony controlled the wealthier, more populous half of the Roman world:

- The entire Greek East

- Asia Minor

- Syria

- Judaea

- Cyprus

- Parts of Thrace and Asia

Cleopatra’s Egypt was the richest kingdom bordering Roman territory. It supplied:

- Enormous quantities of grain (vital for feeding Rome)

- Gold and silver

- Timber, papyrus, linen

- A powerful navy

- A strategic position controlling trade routes

When Antony began granting Roman provinces and client kingdoms to Cleopatra and their children, Octavian could present it as the dismemberment of the empire for the benefit of a foreign queen.

The fear was not irrational: if Antony and Cleopatra consolidated control over the East and Egypt’s resources, they could field an army and navy capable of challenging Italy itself.

Reason #3 — Cultural Clash and Roman Xenophobia

Roman identity in the late Republic was fiercely proud and deeply suspicious of anything perceived as “un-Roman.” Egypt, in particular, occupied a special place in the Roman imagination: a land of fabulous wealth, ancient monarchy, divine kingship, luxury, and — to Roman eyes — moral decadence.

Cleopatra herself embodied everything that traditionalist Romans feared and despised:

- She was a woman who ruled in her own name

- She presented herself as the living incarnation of Isis

- She spoke multiple languages, including (unusually for a Ptolemy) Egyptian

- She maintained an opulent, Hellenistic court that openly blended Greek, Egyptian, and now Roman elements

Mark Antony’s behavior only intensified these anxieties. After his winter with Cleopatra in Alexandria in 41–40 BC, and especially after their renewed alliance in the mid-30s, Antony began adopting the outward trappings of Hellenistic kingship:

- He dressed in the Greek style

- He allowed himself to be addressed as Dionysus-Osiris

- He participated in public ceremonies alongside Cleopatra-Isis

- He held symposia and banquets on a scale that shocked even his own officers

To conservative Romans, this was not mere cultural adaptation. It was betrayal. Antony had “gone native.” Worse, he appeared to have surrendered his Roman masculinity to an Eastern queen.

Octavian seized on this cultural revulsion with devastating effectiveness. He positioned himself as the defender of mos maiorum — the ancestral customs and virtues of Rome — against a dangerous foreign corruption. His propaganda repeatedly contrasted:

- Roman discipline, simplicity, and martial virtue vs.

- Egyptian luxury, effeminacy, superstition, and servility

This was not subtle prejudice; it was a calculated appeal to the deepest anxieties of the Roman elite and the Italian heartland. The idea that Rome’s capital might one day be ruled from Alexandria — or that Roman legions might take orders from an Egyptian queen — was psychologically intolerable to many.

Reason #4 — Octavian’s Masterful Propaganda Campaign (The Decisive Weapon)

Octavian was not the greatest general of his generation (that title belonged to Agrippa), but he was arguably the greatest political operator in Roman history. His handling of the Antony–Cleopatra threat is a textbook case of information warfare in antiquity.

Key elements of his propaganda included:

- War declared on Cleopatra, not Antony In 32 BC, when the Second Triumvirate’s legal term expired, Octavian arranged for war to be formally declared — not on Antony (a fellow Roman and triumvir), but on Cleopatra alone. This brilliant maneuver allowed him to frame the conflict as a patriotic defense of Rome against a foreign aggressor rather than another civil war.

- The “Donations of Alexandria” as treason Octavian publicized (and likely exaggerated) Antony’s territorial grants to Cleopatra and their children, presenting them as the illegal giveaway of Roman provinces to a foreign dynasty.

- Antony’s will The dramatic reading of Antony’s alleged will in 32 BC was a masterstroke. Whether the document was genuine, partially forged, or entirely fabricated is still debated by historians. What is clear is that Octavian used it to devastating effect: the claim that Antony wished to be buried in Egypt and that he intended to make Alexandria the new seat of power crystallized Roman fears.

- Portrayal of Antony as enslaved by love Octavian’s agents spread stories of Antony’s drunkenness, his dancing at Cleopatra’s court, his worship of foreign gods, and — most damningly — his emasculation at the hands of a cunning woman. These accusations tapped into Roman anxieties about masculinity, self-control, and national identity.

- Cleopatra as the archetypal foreign seductress Cleopatra was transformed into a stock figure of Eastern danger: beautiful, manipulative, sexually insatiable, and determined to enslave Roman men and Roman liberty itself.

Ancient sources — Plutarch’s Life of Antony, Cassius Dio’s Roman History, Suetonius’s Life of Augustus — all preserve traces of this propaganda campaign. Even Virgil, writing a decade later in the Aeneid, would echo it in his portrayal of Dido and the dangers of Eastern entanglement.

Modern historians (Adrian Goldsworthy, Mary Beard, Josiah Osgood, among others) generally agree: while some of Octavian’s accusations contained kernels of truth, the overall picture was heavily distorted to serve a single purpose — to make Antony and Cleopatra politically radioactive in Italy.

How Shakespeare Dramatizes Octavian’s Distrust and Roman Fears

Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra (written c. 1606–1607) does not attempt a documentary retelling. Instead, it takes the historical framework and distills it into one of the most complex tragedies in the English language.

Shakespeare’s Octavius Caesar is cold, disciplined, politically ruthless — almost a personification of Roman reason of state. He never raises his voice; he never loses control. He understands power in terms of necessity rather than passion.

Key moments in the play that echo the real historical distrust:

- The opening scene in Alexandria, where Roman soldiers express disgust at Antony’s “Egyptian” behavior (“Nay, but this dotage of our general’s / O’erflows the measure”)

- Octavius’s anger when he learns Antony has married Cleopatra and treated Octavia with contempt

- The repeated Roman references to Cleopatra as a “whore,” “ribaudred nag,” and “triple-turned whore” — language that closely mirrors surviving fragments of Augustan propaganda

- Octavius’s insistence on separating personal affection from political duty (“Let us be cleared of our griefs by reason”)

Yet Shakespeare does not simply take Octavian’s side. He gives Antony and Cleopatra magnificent, almost mythic dignity in their passion and defiance. The tragedy lies precisely in the irreconcilable clash between two worldviews:

- Rome’s austere, duty-bound, imperial logic vs.

- The ecstatic, boundary-dissolving love of Antony and Cleopatra

In this sense, Shakespeare transforms Octavian’s historical distrust into something more universal: the eternal tension between political necessity and human desire.

The Climax — From Distrust to War and the Battle of Actium (31 BC)

By the beginning of 31 BC, the propaganda war had done its work. Most of Italy and the western provinces rallied behind Octavian. Antony and Cleopatra, meanwhile, concentrated their forces in western Greece and the Ionian Sea.

Antony commanded roughly 100,000 infantry and 12,000 cavalry — a formidable army on paper. Cleopatra contributed 200 Egyptian warships and an enormous war chest. Yet the coalition suffered from serious structural weaknesses:

- Many of Antony’s senior officers and senators defected to Octavian (including future consul Gaius Sosius and Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus)

- Morale was uneven; Roman soldiers resented fighting under the banners of an Egyptian queen

- Supply lines stretched across the Adriatic were vulnerable

Octavian’s genius lay in delegation. He entrusted the naval campaign to his childhood friend and finest admiral, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa. In a series of brilliant maneuvers during the summer of 31 BC, Agrippa captured key supply bases (Methone, Corcyra) and isolated Antony’s fleet at the Gulf of Ambracia (modern Ambracia/Actium).

On September 2, 31 BC, the two fleets finally met at the Battle of Actium.

Popular imagination — fed by Shakespeare and Hollywood — pictures a heroic last stand. The reality was far more tactical and, for Antony, catastrophic.

- Antony had about 230 heavy warships (many quinqueremes and larger)

- Octavian-Agrippa fielded around 400 lighter, more maneuverable Liburnian ships

- When the centers engaged, Cleopatra’s 60-ship reserve squadron suddenly hoisted sail and broke through the Roman line toward open water

- Antony transferred from his flagship to a faster vessel and followed her

- Roughly 200 of Antony’s ships were captured or burned; only a fraction escaped

Historians still debate Cleopatra’s motives. Was it panic? A pre-arranged signal to preserve the treasury ships? A strategic decision to avoid total annihilation? Whatever the truth, the flight of the queen and Antony’s decision to abandon his fleet shattered his reputation among the remaining legions. Within weeks his land army surrendered en masse.

Aftermath: Alexandria, Suicide, and the End of the Ptolemaic Dynasty

Antony and Cleopatra retreated to Alexandria. For nearly a year they lived in a strange limbo — feasting, planning, despairing. Antony formed a drinking club called “The Inimitable Livers”; Cleopatra experimented with poisons on condemned prisoners.

In August 30 BC Octavian invaded Egypt. Antony’s last forces deserted. On August 1, believing Cleopatra already dead, Antony fell on his sword (though he lingered for hours). Cleopatra, determined to negotiate, allowed herself to be taken into custody.

When Octavian made clear he intended to parade her in a Roman triumph, Cleopatra committed suicide — probably by asp venom — on August 10 or 12, 30 BC. She was 39.

Octavian’s final act of ruthlessness came days later: he ordered the execution of 17-year-old Caesarion as he fled toward India. According to Plutarch, Octavian quoted Homer: “It is not good to have many Caesars.”

Antony and Cleopatra’s three younger children were spared and raised in Rome by Octavia.

Lasting Consequences — Why Octavian’s Victory Mattered

The defeat of Antony and Cleopatra did not merely eliminate two rivals. It ended the Roman Republic.

- The Second Triumvirate was dissolved

- Octavian became the undisputed master of the entire Mediterranean world

- In 27 BC the Senate granted him the honorific Augustus and voted him sweeping powers disguised as republican offices

Egypt was annexed as Octavian’s personal estate — its grain and gold underwriting the new imperial system. The Roman army was professionalized and loyal to the princeps rather than individual generals. Civil war, which had plagued Rome for a century, finally ceased.

Cleopatra’s reputation suffered lasting damage. Augustan poets (Virgil, Horace, Propertius) and later historians transformed her into the archetype of the dangerous foreign seductress — a stereotype that endured for two millennia.

Yet modern scholarship has begun to rehabilitate her. Far from a mere temptress, Cleopatra VII was one of the most capable Hellenistic rulers of her era — multilingual, intellectually brilliant, and politically astute. Her tragedy, like Antony’s, was to confront a man who played the Roman political game more ruthlessly than anyone before or after.

Expert Insights & Common Misconceptions

- Was Antony really planning to move the capital to Alexandria? Almost certainly propaganda. No reliable source before Octavian’s campaign mentions such a plan.

- Was Antony’s will forged? Scholars are divided. The contents were suspiciously convenient for Octavian, yet Roman law required wills to be deposited with the Vestal Virgins — making outright forgery risky.

- Did Cleopatra “seduce” Antony and Octavian? The historical record suggests calculated political alliances rather than simple seduction. Both Romans pursued her as much as she pursued them.

- How accurate is Shakespeare? Remarkably faithful to Plutarch’s Life of Antony (Shakespeare’s primary source), but deliberately anachronistic and poetic. Shakespeare compresses years into months, heightens the passion, and gives Cleopatra a grandeur the Roman sources deny her.

Recommended modern works:

- Stacy Schiff, Cleopatra: A Life (2010)

- Adrian Goldsworthy, Antony and Cleopatra (2010)

- Duane W. Roller, Cleopatra: A Biography (2010)

- Barry Strauss, The War That Made the Roman Empire (2022)

FAQs

1. Why did Octavian declare war on Cleopatra instead of Antony? To avoid the stigma of another Roman civil war and to unite Italy against a foreign enemy.

2. Was Antony’s will real or forged by Octavian? Likely genuine but selectively leaked and interpreted. The burial clause and bequests to Cleopatra’s children were politically explosive regardless of authenticity.

3. Did Cleopatra really seduce and control Mark Antony? Their relationship was a genuine partnership of equals — political, military, and romantic. Roman sources exaggerate her “control” to explain away Antony’s choices.

4. How accurate is Shakespeare’s portrayal compared to history? Shakespeare follows Plutarch closely in events and character but transforms historical propaganda into profound tragedy, giving voice and dignity to both lovers.

5. What happened to Antony and Cleopatra’s children after Actium? Alexander Helios and Ptolemy Philadelphus disappear from the record (possibly killed). Cleopatra Selene II was married to King Juba II of Mauretania and became queen herself.

Why did Octavian not trust Antony and Cleopatra to rule?

Because, in his calculating mind, they represented an alternative future for the Mediterranean world — one in which Rome shared power with a Hellenistic-Egyptian dynasty, where Caesar’s blood heir was not an adopted Italian aristocrat but a half-Egyptian prince, where the capital might one day sit on the Nile instead of the Tiber.

Octavian — soon to be Augustus — could not permit that future. His distrust was partly genuine strategic calculation, partly inherited Roman prejudice, and wholly amplified by one of history’s most successful propaganda campaigns.

Shakespeare understood the human cost of that calculation. In Antony and Cleopatra he gives us not victors and villains, but two flawed, magnificent lovers who chose passion over empire — and paid the ultimate price.

Their story remains one of the most gripping in Western history precisely because it forces us to ask: What happens when love and duty, East and West, individual desire and collective destiny collide?

The Roman Empire was born from Octavian’s refusal to share power. Whether that was triumph or tragedy depends, in the end, on where you stand when the asp strikes.