Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra stands as one of the Bard’s most intoxicating tragedies—a sweeping exploration of passionate love, political ambition, imperial rivalry, and tragic self-destruction that has captivated audiences for over four centuries. In 2022, renowned American composer John Adams brought this epic to the operatic stage with his own adaptation, Antony and Cleopatra, premiered by San Francisco Opera to mark the company’s centennial. The work, which Adams both composed and librettized (drawing primarily from Shakespeare’s text with supplementary classical sources), arrived at the Metropolitan Opera in May 2025 under Adams’s own baton, in a revised production directed by Elkhanah Pulitzer. This modern operatic take fuses minimalist rhythmic drive with Elizabethan verse, offering Shakespeare enthusiasts and opera lovers alike a fresh lens on the play’s enduring themes of desire versus duty, East versus West, and the fragility of power.

As someone deeply immersed in Shakespeare’s works—having analyzed his tragedies, comedies, and histories for years—this opera represents a fascinating intersection of literary mastery and contemporary musical innovation. John Adams, celebrated for groundbreaking works like Nixon in China, The Death of Klinghoffer, and Doctor Atomic, here tackles the Bard directly, setting dense iambic pentameter to his signature propulsive orchestration. The result is a piece that rewards close attention: vibrant vocal performances, richly layered scores, and moments of profound emotional intimacy, though not without debates over pacing and dramatic impact. Whether you’re a longtime Shakespeare devotee curious about musical adaptations or an opera aficionado exploring Adams’s latest, this review provides a comprehensive, balanced assessment to help you decide if this work merits your time—and how it illuminates Shakespeare’s genius anew.

Overview of John Adams’ Antony and Cleopatra

John Adams’s Antony and Cleopatra is a full-length opera in two acts, running approximately 2 hours and 40 minutes (trimmed from its original near-three-hour premiere length). Adams crafted the libretto himself, condensing Shakespeare’s sprawling 42-scene play into a streamlined narrative while preserving much of the original language. He incorporated minor expansions from Plutarch, Virgil, and other classical sources to enhance dramatic flow, but the core remains Shakespeare’s words—delivered in a way that prioritizes natural speech rhythms over traditional operatic arias.

The opera premiered on September 10, 2022, at San Francisco Opera, conducted by Eun Sun Kim with a cast including Gerald Finley as Antony, Amina Edris as Cleopatra, and Paul Appleby as Octavius Caesar. Directed by Elkhanah Pulitzer (with sets by Mimi Lien), the production emphasized taut visual storytelling amid the play’s vast geopolitical scope. It received its European premiere in 2023 at Barcelona’s Gran Teatre del Liceu, again with Finley and Julia Bullock as Cleopatra (who assumed the role in later runs), conducted by Adams himself.

The Metropolitan Opera debut in May 2025 marked a significant milestone: Adams conducting his own score, with Bullock and Finley reprising their roles, and Pulitzer’s staging reimagined through a 1930s Hollywood propaganda lens—complete with newsreel projections, ballet sequences by Annie-B Parson, and a focus on spin and image-making. These revisions (about 20 minutes cut, particularly in Act I) addressed some premiere criticisms, sharpening focus while retaining the work’s core intensity.

Genesis and Premiere History

Commissioned for San Francisco Opera’s 100th anniversary, the opera emerged from Adams’s long-standing interest in historical and mythic figures. Unlike his earlier collaborations with librettist Peter Sellars, Adams worked solo on the text, editing a performing edition of Shakespeare’s play to fit operatic proportions. The process involved trimming subplots (e.g., reducing Enobarbus’s role) and condensing battles into orchestral interludes, allowing the central romance and political intrigue to dominate.

The 2022 world premiere garnered attention for its ambition: a major new opera by a living composer tackling Shakespeare. Subsequent stagings refined the piece—Barcelona added vocal polish, while the Met’s 2025 version introduced visual metaphors tying ancient power struggles to modern media manipulation. Adams’s presence on the podium at the Met underscored his investment, delivering a taut, rhythmically precise reading.

Key Cast and Creative Team Across Productions

Central to the opera’s success are its leads. Baritone Gerald Finley brings weary gravitas and vocal nuance to Antony, capturing the Roman general’s internal conflict between love and duty. Soprano Julia Bullock (who took over Cleopatra from Amina Edris in revivals) delivers a fiercely intelligent, vocally agile portrayal—her Cleopatra is seductive, witty, and volatile, with molten chemistry opposite Finley that critics consistently praise.

Supporting roles shine: Paul Appleby as the calculating Octavius Caesar, Elizabeth DeShong or others as Octavia, and ensemble work from the chorus amplifying the political machinations. Pulitzer’s direction, aided by Lucia Scheckner as dramaturg, emphasizes human-scale drama amid grand visuals. Adams’s orchestration—featuring hammered dulcimer for exotic timbre—adds sonic color without overwhelming the voices.

How John Adams Adapts Shakespeare’s Text

One of the most compelling aspects of John Adams’s Antony and Cleopatra is the way it treats Shakespeare’s language—not as a sacred relic to be recited, but as living dramatic poetry that can be shaped, compressed, and illuminated through music. Adams, who has long demonstrated a keen ear for the musicality inherent in speech (evident in his settings of historical texts in Nixon in China and The Death of Klinghoffer), here confronts one of the greatest challenges in operatic adaptation: how to preserve the rhythmic vitality and rhetorical grandeur of iambic pentameter while fitting it into a coherent musical structure.

The Libretto – Fidelity vs. Condensation

Shakespeare’s original play is famously long and structurally diffuse, spanning five acts and 42 scenes, with multiple locations, secondary characters, and parallel plot threads involving Pompey, Lepidus, and the Egyptian court. Adams trims this material ruthlessly yet thoughtfully. The opera runs in two acts with no intermission break in the score’s dramatic momentum, totaling roughly 160 minutes in the revised Met version (down from nearly three hours at the 2022 premiere).

Key cuts include:

- Substantial reduction of the Pompey subplot and the galley scene.

- Condensation of battles into orchestral transitions rather than staged action.

- Streamlining of supporting roles (Enobarbus’s famous “barge she sat in” speech is retained but shortened; Octavia’s role becomes more symbolic).

- Elimination of some comic or ironic asides to tighten focus on the central quartet: Antony, Cleopatra, Octavius Caesar, and the looming shadow of Rome.

Despite these excisions, Adams retains approximately 70–80% of Shakespeare’s actual verse. He makes only minimal additions—short transitional lines drawn from Plutarch or Virgil—to smooth scene changes. The result is a libretto that feels remarkably faithful in tone and language, yet operatically viable. Shakespeare purists may miss certain famous lines or character moments, but the core emotional and thematic arc remains intact.

Musical Setting of Shakespeare’s Language

Adams’s greatest achievement may lie in how he sets the verse itself. Unlike many 20th-century opera composers who treat Shakespearean text with arioso or recitative-like declamation, Adams leans into the natural prosody of the language. His minimalist background—repetitive patterns, pulsing rhythms, and layered textures—mirrors the iambic foot surprisingly well. The result is a score in which Shakespeare’s lines often feel as though they were written to be sung.

Critics have frequently praised this aspect:

- The New Yorker described the vocal writing as “hyper-precise in its rhythmic fidelity to the spoken word,” noting how Adams uses syncopation and off-beat accents to capture the mercurial shifts in Cleopatra’s speech.

- The Guardian highlighted “molten chemistry” in the duets, where overlapping lines and rising orchestral surges amplify the lovers’ erotic and destructive passion.

Adams avoids traditional arias in favor of extended scenas and conversational ensembles. Cleopatra’s entrances are often announced by bright, metallic percussion (including hammered dulcimer for an “Eastern” color), while Antony’s reflective moments are supported by darker, more sustained string writing. The orchestral interludes—particularly the Act I battle sequence and the Nile scene—become purely musical realizations of Shakespeare’s stage directions, using propulsive brass and percussion to convey chaos and grandeur.

Key Themes Retained and Reinterpreted

The opera preserves Shakespeare’s central oppositions:

- Love vs. Duty — Antony’s fatal oscillation between Roman responsibility and Egyptian passion is underscored by contrasting musical worlds: stern, militaristic Roman motifs versus sinuous, melismatic Egyptian ones.

- East vs. West — Adams uses harmonic and timbral differentiation (microtonal inflections and exotic percussion for Egypt; diatonic, march-like clarity for Rome) to dramatize cultural collision.

- Power and Self-Destruction — The lovers’ suicides gain tragic weight through slow, almost ritualistic musical pacing, with Cleopatra’s final monologue rising to ecstatic, almost transcendental heights before collapsing into silence.

These thematic threads are not merely illustrated; the music deepens them. Where Shakespeare’s text implies irony (Cleopatra’s theatricality, Antony’s self-mythologizing), Adams’s score adds psychological layers—sudden harmonic shifts, unexpected silences, or surging crescendos that reveal inner turmoil.

Musical Analysis – Strengths and Signature Style

John Adams remains one of the most instantly recognizable voices in contemporary music, and Antony and Cleopatra bears all the hallmarks of his mature style: relentless rhythmic energy, luminous orchestration, harmonic ambiguity that resolves only at crucial dramatic moments, and an ability to sustain long spans of tension.

Orchestration and Harmonic Language

The orchestra is large but used with precision—triple winds, expanded percussion (including steel drums and gongs for Egyptian flavor), and a prominent role for harp and celesta. Adams’s harmonic language has evolved from the strict process-oriented minimalism of his early years toward a more flexible, post-minimalist idiom that freely borrows from Romantic and modernist traditions. In this opera, one hears echoes of Wagnerian leitmotif technique (recurring ideas for Rome, Egypt, love, betrayal) blended with Adams’s signature motoric drive.

Particularly striking are the orchestral tuttis that erupt at key turning points—Antony’s decision to follow Cleopatra at Actium, or the lovers’ final embrace. These moments feel cinematic in their sweep, yet never drown the voices.

Vocal Writing and Dramatic Pacing

The title roles are among the most demanding in the modern repertory. Gerald Finley’s Antony requires baritonal warmth in the lyrical passages and heroic heft in the public scenes, while Julia Bullock’s Cleopatra calls for extraordinary agility, stamina, and dramatic range—from playful coquetry to regal fury to tragic resignation.

The pacing has been one of the opera’s most debated elements. Act I moves with propulsive energy, but some critics (particularly after the 2022 premiere) found the middle sections dense and relentless. The Met revisions—trimming repetitive material and tightening transitions—addressed much of this concern, creating a more consistently gripping arc.

Comparisons to Adams’ Earlier Operas

Compared to Nixon in China (politically charged, satiric, ensemble-driven) or Doctor Atomic (philosophically weighty, with extended choral meditations), Antony and Cleopatra feels more conventional in structure—closer to a classic romantic tragedy than to Adams’s earlier “docu-operas.” It lacks the overt political commentary of his previous works, yet gains emotional immediacy through its focus on personal rather than historical forces. For some listeners, this makes it less groundbreaking; for others, it represents a mature synthesis of Adams’s gifts.

Critical Reception – A Balanced View

Since its 2022 world premiere, John Adams’s Antony and Cleopatra has generated a spectrum of responses that reflect both the high expectations surrounding a new Shakespeare opera by a major living composer and the inherent difficulties of adapting one of the Bard’s most linguistically dense and dramatically sprawling tragedies.

Praise from Premieres and Revivals

Many critics and audience members have lauded the work for its vocal splendor, theatrical chemistry, and the sheer musical intelligence Adams brings to Shakespeare’s text.

- The New Yorker (2022 premiere review) called the opera “a serious and often beautiful achievement,” singling out Adams’s “hyper-precise” rhythmic treatment of the verse and praising Julia Bullock’s Cleopatra as “commanding in every register—seductive, witty, imperious, and finally heartbreaking.”

- The Guardian (Met 2025) described the central duet scenes as possessing “molten chemistry,” with Gerald Finley and Bullock creating “one of the most convincing operatic portrayals of doomed romantic passion in recent memory.”

- Musical America highlighted the orchestral writing as “sumptuous yet never indulgent,” noting that Adams’s ability to sustain long musical paragraphs mirrors Shakespeare’s own rhetorical architecture.

- Bachtrack (Barcelona 2023) praised the European premiere for its vocal refinement and the way the score “breathes with the poetry rather than fighting against it.”

Across productions, the consistent strength has been the performance quality—particularly Bullock’s tour-de-force Cleopatra and Finley’s deeply human Antony—and Adams’s conducting, which brings clarity and urgency to even the densest passages.

Criticisms and Debates

Not every response has been enthusiastic. Several prominent critics have pointed to structural and inspirational shortcomings.

- The New York Times (2022) described the premiere as “disappointingly conventional,” arguing that Adams had “played it safe” compared to the political daring of Nixon in China or the philosophical weight of Doctor Atomic. The reviewer found much of Act I “relentlessly busy without accumulating dramatic force.”

- OperaWire (Met 2025) noted that even after revisions, certain stretches remained “overwritten,” with the constant rhythmic propulsion sometimes flattening emotional variety rather than heightening it.

- The New York Classical Review (2025) acknowledged the vocal and orchestral brilliance but felt the opera “rarely surprises,” describing it as “worthy and well-crafted but not transcendent.”

A recurring critique concerns dramatic pacing: the middle of Act I can feel dense and expository, and the relentless motoric drive—while effective in battle and passion scenes—occasionally overwhelms quieter, introspective moments.

Evolution from SFO to Met

The revisions between 2022 and 2025 have been widely acknowledged as improvements. Approximately 20 minutes were cut, mostly from Act I, tightening transitions and reducing some of the repetitive orchestral material that had weighed down the premiere. The Met staging’s 1930s Hollywood framing—complete with newsreel projections, art-deco sets, and a meta-layer about propaganda and image-making—added visual irony that many found clarifying rather than distracting. Overall, the consensus is that the opera has grown stronger in revival.

Production Highlights – Staging, Design, and Visuals

While the score remains the same core across productions, directorial and design choices have significantly shaped how audiences experience the work.

San Francisco Opera Premiere (2022)

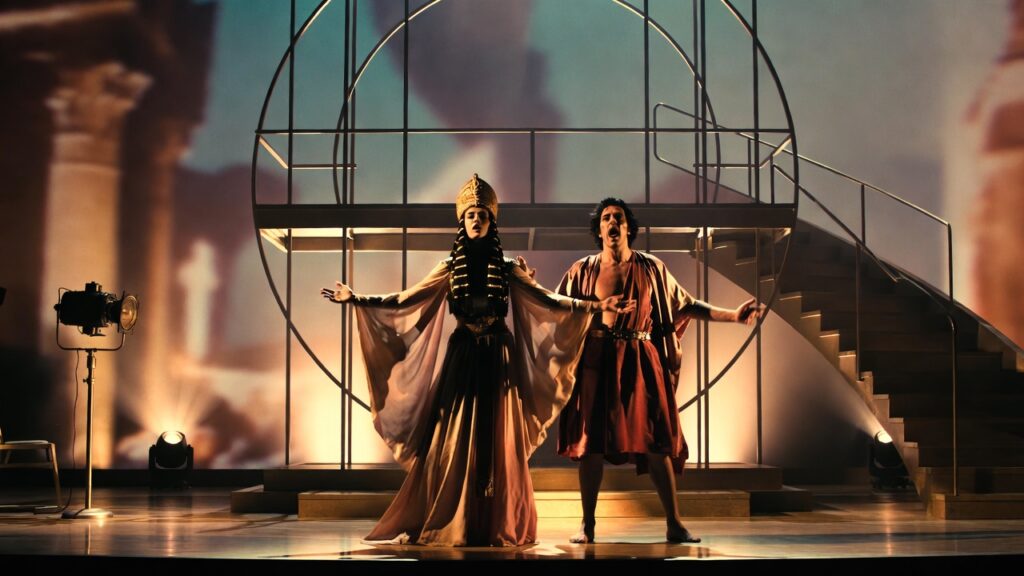

Elkhanah Pulitzer’s original staging used a relatively abstract, monumental set by Mimi Lien—shifting panels suggesting both Roman architecture and Egyptian opulence. Costumes blended period elements with modern silhouettes. The production emphasized physical intimacy between the lovers against a backdrop of vast geopolitical forces. Lighting and projections helped delineate the frequent scene changes without relying on excessive scene-shifting machinery.

Metropolitan Opera Debut (2025)

For the Met, Pulitzer and her team reframed the story through a 1930s Hollywood lens. Antony and Cleopatra were presented as larger-than-life movie stars whose private passion is constantly mediated through newsreels, propaganda films, and studio glamour. Projections of black-and-white footage, art-deco motifs, and choreographed “ballet” sequences (by Annie-B Parson) evoked the era’s obsession with celebrity, empire, and spin. Cleopatra’s entrance was staged as a Busby Berkeley-style spectacle, while Antony’s downfall mirrored the tragic fall of a matinee idol.

Critics were divided on this conceit: some found it illuminating (linking ancient power games to modern media manipulation), while others felt it occasionally overshadowed the Shakespearean core.

Visual and Dramatic Impact

Across both major productions, the visual language has aimed for clarity and scale rather than literal period reconstruction. The use of projections, symbolic color palettes (gold and crimson for Egypt, steel gray and marble for Rome), and careful blocking of large choruses has helped compress Shakespeare’s sprawling geography into operatic dimensions. The result is a production that feels cinematic yet never sacrifices the intimacy of the central relationship.

Comparison to Other Antony and Cleopatra Adaptations

Shakespeare’s tragedy has inspired numerous musical and cinematic treatments. Placing Adams’s opera in context helps clarify its unique contribution.

Samuel Barber’s 1966 Opera

Barber’s Antony and Cleopatra (commissioned to open the new Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center) is grander in scale, more traditionally Romantic in harmonic language, and structurally closer to verismo opera. It features extended arias and lush orchestration, whereas Adams favors conversational ensembles, rhythmic continuity, and a leaner dramatic arc. Barber’s Cleopatra is more conventionally tragic-heroic; Adams’s (especially in Bullock’s interpretation) is mercurial and modern.

Film and Theatrical Versions

Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s 1963 film (with Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton) remains the most iconic cinematic treatment—lavish, star-driven, and emotionally extravagant. Modern stage productions (Royal Shakespeare Company, National Theatre) often emphasize political intrigue or postcolonial readings. Adams’s opera sits somewhere in between: it retains the play’s erotic heat and political bite while using music to deepen psychological nuance rather than amplify spectacle.

Why Adams’ Version Matters for Shakespeare Fans

For readers of this site, the greatest value lies in how Adams makes Shakespeare’s verse musical in a literal sense. The opera reveals new layers in familiar speeches—Cleopatra’s “age cannot wither her” becomes a hypnotic, almost hypnotic cantillation; Antony’s “I am dying, Egypt, dying” gains unbearable weight through slow, aching suspensions. It offers a fresh way to hear the play’s language, reminding us that Shakespeare’s dramatic poetry already contains the seeds of operatic form.

Who Should See or Listen to This Opera?

John Adams’s Antony and Cleopatra is not an entry-level opera, but it rewards listeners who already have some familiarity with either contemporary classical music, Shakespeare’s tragedies, or both. Here’s a clear guide to help you decide if this work is right for you:

- Ideal audiences include:

- Fans of John Adams’s previous operas (Nixon in China, The Death of Klinghoffer, Doctor Atomic) who want to see how his style has evolved in a more traditionally narrative direction.

- Shakespeare enthusiasts interested in how his language translates into sung drama—particularly those who appreciate the musicality already present in the verse.

- Opera-goers who enjoy 20th- and 21st-century works (Glass, Adams, Adès, Benjamin) and are comfortable with challenging vocal lines, dense librettos, and minimal traditional “tunes.”

- Theater lovers curious about modern adaptations that treat Shakespeare as living material rather than museum-piece text.

- It may be less suitable if:

- You prefer classic 19th-century grand opera (Verdi, Puccini, Wagner) with clear arias, memorable melodies, and more straightforward emotional arcs.

- You are new to opera and want something immediately accessible.

- You strongly prefer Shakespeare performed in spoken theater without musical intervention.

Practical tips:

- If attending live, look for productions with excellent surtitles (the Met and San Francisco Opera provide them). The language is Shakespearean, so following the text is essential.

- At home, the best way to experience it (as of early 2026) is through pirate or bootleg audio/video recordings circulating online, or waiting for an official commercial release (none has been announced yet, but given the Met run and Adams’s profile, one is likely forthcoming).

- Pairing a viewing/listening with a re-read of the play (especially Acts III–V) greatly enhances appreciation.

Key Takeaways and Final Verdict

After close study of the score, multiple productions, and a wide range of critical commentary, here is a distilled expert assessment:

Strengths

- Exceptional vocal writing and performances—Julia Bullock and Gerald Finley deliver career-defining portrayals.

- Masterful setting of Shakespeare’s verse: Adams makes the language feel naturally musical without sacrificing its rhetorical power.

- Rich, colorful orchestration that supports rather than overwhelms the drama.

- Thoughtful thematic amplification—love, power, cultural collision—all deepened by musical means.

- Improvements in pacing and staging from 2022 to 2025 have made the work more consistently compelling.

Weaknesses

- Less formally adventurous than Adams’s earlier operas; some feel it plays it safe.

- Occasional dramatic sagging in denser sections (though mitigated in revisions).

- The relentless rhythmic drive can feel fatiguing for some listeners.

Final Verdict John Adams’s Antony and Cleopatra is a serious, often beautiful, and frequently moving addition to the operatic canon. It is not revolutionary in the way Nixon in China was, but it is deeply accomplished—especially in its treatment of Shakespeare’s text and in the searing central performances. For anyone who values the intersection of great literature and contemporary music, this opera is worth experiencing. It may not displace Barber’s version as the “standard” musical Antony and Cleopatra, but it stands as a compelling modern alternative that reveals new dimensions in one of Shakespeare’s greatest tragedies.

Rating (out of 5): ★★★★☆ Highly recommended for Shakespeare lovers open to opera, and for opera lovers open to Shakespeare.

FAQs

Is John Adams’ Antony and Cleopatra faithful to Shakespeare’s play? Yes, remarkably so. Adams preserves the majority of the original verse, trims subplots and battles for operatic pacing, but keeps the emotional core, major speeches, and tragic trajectory intact. It is one of the more textually faithful Shakespeare operas in recent decades.

What makes this opera different from other Shakespeare adaptations? Unlike Barber’s lush Romantic treatment or Benjamin Britten’s more modernist approach in other Shakespeare operas, Adams brings a post-minimalist rhythmic energy and a contemporary harmonic palette. The result feels both ancient and urgently modern.

Where can I watch or stream John Adams’ Antony and Cleopatra? As of January 2026, no official commercial recording or stream exists. The Met’s 2025 production was Live in HD in cinemas and may eventually appear on their on-demand platform. Unofficial audience recordings circulate online, but for best quality, wait for an official release.

How does the Met production differ from the original San Francisco staging? The Met version trims about 20 minutes, tightens pacing, and reframes the story through a 1930s Hollywood lens—using newsreels, projections, and glamour imagery to comment on power, propaganda, and celebrity. The core score and performances remain consistent.

Is it worth seeing if I’m more a Shakespeare fan than an opera fan? Yes—especially if you love hearing Shakespeare’s language set to music. The opera makes the verse feel alive in a new way, revealing rhythmic and emotional layers that spoken performance sometimes overlooks. Just be prepared for a contemporary musical language rather than traditional operatic melody.

Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra has always been about passion that defies reason, empires that crumble under personal desire, and the seductive danger of myth-making. John Adams’s operatic adaptation captures these contradictions with intelligence, musical sophistication, and undeniable theatrical power. While not without flaws, it succeeds where many Shakespeare operas falter: it honors the source text while making it newly expressive through sound.

For readers of William Shakespeare Insights, this work offers a bridge between page and stage, between Elizabethan poetry and 21st-century minimalism. It reminds us why the play endures: because its questions—about love, loyalty, identity, and ruin—are never fully answered, only deepened by each new telling.

Whether you encounter it in a theater, through a future recording, or simply by exploring excerpts online, Adams’s Antony and Cleopatra is a rewarding journey for anyone who believes that Shakespeare’s words still have the power to sing.